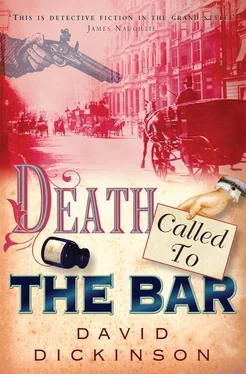

David Dickinson - Death Called to the Bar

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Dickinson - Death Called to the Bar» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death Called to the Bar

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death Called to the Bar: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death Called to the Bar»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death Called to the Bar — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death Called to the Bar», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

McDonnell listened gravely to Lady Lucy’s account of her husband’s situation. ‘I would stay longer if I could but I have to return to the Prime Minister, Lady Powerscourt. I have often brought your husband messages from Lord Salisbury in the past. I have another one for him today. Lord Salisbury says that he is weary of office, and, between ourselves, expects to leave it soon. He does not expect to live very long in retirement. But his message to Lord Powerscourt is very clear. He is damned if he is going to have to attend Powerscourt’s funeral. He expects, nay, he orders that Powerscourt should attend his, whenever that may be. Your husband, Lady Powerscourt, in the Prime Minister’s words, is under government orders to recover.’

Johnny Fitzgerald took the last watch that day. The children were asleep. He hoped Lady Lucy was too. He walked up and down the room for a long time, lost in the memories of his and Powerscourt’s lives together. They had been to so many places after leaving Ireland and had shared so many adventures. He thought of Lady Lucy and the enormous strain she must be under. Johnny had seen how, more than ever now, all the threads of this house and of Francis’s life ran through her hands. Lady Lucy had to determine the altered routines of the house with the cook and the domestic staff. She had to liaise with the nurses and with the frequent presence of Dr Tony, who demanded total attention when he came. She had to look after the two oldest children who stitched on, at her instructions, he suspected, a mask of cheer and optimism about their father’s chances of recovery during the day. At night, he knew, the hope deserted them and Thomas and Olivia fled to weep in their mother’s bed. Johnny had heard them crying from two floors further up the night before. And all the time, reassuring her children, organizing her household, welcoming the visitors and ordering yet more tea, Lady Lucy must, Johnny felt sure, have her own private nightmares. Would Francis pull through? Could she imagine life without him? How would the children cope? And this worry above all, he was sure, how would the twins, so tiny and so young, cope with life without their father?

At about half past eleven Johnny sat down by the side of the bed. He began telling his friend stories about the officers and men they had known in India, the eccentric, the mad, the brave, the cowards, the ones who liked the Indians, the ones who despised Indians, the very occasional ones who went completely native. Most of these stories contained jokes, some of them very good jokes. But the laughter Johnny hoped for did not come. As the church clock rang the midnight hour Lord Francis Powerscourt was still in a coma, drifting uncertainly between life and death.

17

Edward and Sarah came round to Manchester Square in the middle of the fifth afternoon. They brought fresh news of the Inn. There had been little sadness over the suicide of Barton Somerville, Edward reported. The remaining benchers, on the instigation of Maxwell Kirk, had all resigned to mark their failure to rein in the previous Treasurer. There had, Edward and Sarah quickly realized, been considerable progress in the story of Treasure Island in the sick room. Olivia had quickly mastered the production of Black Spots, supposed to bring bad luck to those holding them, and had pressed one into the palm of virtually every member of the household. Edward himself had collected two already and the unfortunate butler was marked with four of the things. Edward was able to bring another dimension to the story. While Sarah took over the job of reading Treasure Island , Edward, with the aid of some elastic, some very long socks and some string, taught the children how to tie one leg up so the foot was attached to the thigh. Two retired broom handles were discovered in the pantry and cut to the appropriate sizes for Thomas and Olivia. With the leg tied up and the broom acting as a crutch they could each pretend to be Long John Silver thumping his way across the boards of their parents’ bedroom that was really the upper deck of the Hispaniola sailing across the oceans to the fabulous island of treasure. Edward regretted that there were no parrots available but he suggested they ask Johnny Fitzgerald to say ‘Pieces of eight’ in his best parrot voice when he next appeared. The only problem in acting out the role of a handicapped pirate in quest of treasure was that it was much more difficult to walk with the broomstick than you might have imagined, even if you were small and supple. The two children kept falling over and giggled helplessly on the floor until some kind person helped them up. If there hadn’t been anybody else around to assist them, Thomas told the assembled company, he and Olivia would be left there until the end of time. Edward assured the children that there was a section of the book, he couldn’t remember exactly which chapter, where the author says it took Long John Silver himself over a year to learn how to walk properly with his crutch. For a brief quarter of an hour the children forgot about their sick father. Then the doctor came in for his afternoon visit, accompanied by Lady Lucy. The children disappeared upstairs. Edward took Sarah by the hand and led her out into Manchester Square.

‘Where are we going, Edward? Are we going to the Wallace Collection to see where Lord Powerscourt was shot?’

‘We are going to the Wallace Collection, Sarah,’ said Edward, as he led her up the drive, ‘but we are not going to the scene of the shooting. I want to take you to look at a painting on the second floor, if I may.’

They walked up the grand staircase where Powerscourt had been shot. They came to one of the smaller rooms on the first floor. High up on the wall by a window was a mythological painting about three feet square. In front of an Arcadian landscape with a brooding sky of dark clouds, it showed the Four Seasons, facing outwards, hand in hand in a stately dance. Autumn, at the rear of the painting, had dry leaves in her hair and represented Bacchus, the God of wine. To the right of Bacchus was Winter with her hair in a cloth to keep out the cold, then Spring, her hair braided like ears of corn, and Summer, linked to Spring on her left and Autumn on her right. The picture was framed on the right by a block of stone that might mark the site of someone’s grave and on the left by a statue showing the youthful and mature Bacchus with a garland. At the bottom edges of the painting two putti played with an hourglass each. The musical accompaniment was provided by Saturn, the god of time, playing on his lyre, and in the clouds above, Apollo, the sun god, drove his chariot across the sky to create the day.

‘It’s called A Dance to the Music of Time ,’ said Edward, looking closely at Apollo’s companions in the clouds. ‘It’s by a Frenchman called Nicolas Poussin. He was always doing stuff like this,’ Edward went on airily, ‘mythological scenes, idealized landscapes, philosophical messages tied up with the poetry of Ovid or somebody like that. I think he painted some of them for a cardinal or some other grand fellow in Rome.’

Sarah was wondering why Edward had brought her here to see it. It was certainly beautiful but there must be a reason. ‘What does it mean?’ she said.

‘Well,’ said Edward, ‘originally it had to do with the myth of Jupiter’s gift of Bacchus, god of wine, to the world after the Seasons complained about the harshness of human life. It could mean lots of things. It could mean we should all be thankful not just for the gift of wine but for the stately order of the seasons which hold our lives in the pattern of their dance. I don’t think these Seasons are dancing very fast, you see. Time is going round at a fairly steady rate. The infants with the hourglasses, of course, represent the passing of time, the vanity of human aspirations, the fact that everything is going to end.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death Called to the Bar»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death Called to the Bar» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death Called to the Bar» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.