David Dickinson - Death of a Pilgrim

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Dickinson - Death of a Pilgrim» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death of a Pilgrim

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death of a Pilgrim: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death of a Pilgrim»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death of a Pilgrim — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death of a Pilgrim», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The case of Shane’s drinking companion, Willie John Delaney, was slightly different. He was short and single with a small beard and worked as a debt collector in north London. He was dying from an incurable disease. He had come to parley with God for his life.

On the other side of the bar two young men were sitting at a table well stacked with empty beer bottles. Christopher, commonly known as Christy, Delaney came from Greystones in County Wicklow. He had bright blue eyes and a great shock of sandy hair. He looked absurdly young, much younger than his eighteen years. His parents were comfortably off and he was going up to Cambridge to read history in the autumn. He thought he could learn some French and see some of the great sites of France. His mother, a deeply religious woman, hoped that the pilgrimage would be good for her boy’s immortal soul. Already she had doubts about it.

His companion was about twenty-five, slim and wiry, brown eyes darting round the room to take in the details of his surroundings. Jack O’Driscoll was a reporter on one of the Dublin newspapers. His editor had given him leave of absence because he thought the experience might broaden his outlook. This pilgrimage, the editor – a pious man in an impious profession – told him, should make him a better reporter. He also offered to take some articles about the journey for his paper. Jack O’Driscoll was one of those fortunate people who seem at home in any surroundings. Before they came to the bar, he pulled out a battered document from his waistcoat.

‘Chap on the paper gave me this,’ he said to Christy cheerfully. ‘He says it’s all you need to order a drink in France. It’s in a sort of pidgin French. Phonetics, I think they call it.’

‘Oon bee air,’ said Christy doubtfully. ‘Oon bee air?’

‘That’s a beer in French,’ said Jack. ‘You’ve got to run the words together, mind you. Hold up two fingers for two beers and so on.’

‘Are you sure?’ said Christy.

‘I am sure,’ said Jack. ‘If you want to impress them with your knowledge of the French language, this is what you say when you need a refill. On core oon bee air.’

‘On core oon bee air,’ Christy sounded more confident now. ‘How do you pay when you get to the end, if you follow me?’

‘Easy,’ said Jack, pointing to the last entry on the piece of paper. ‘Say “com bee yon?” You’ve got to put the question mark at the end of the “yon” now, or it won’t work.’

Miraculously the O’Driscoll method of ordering beers worked well. Christy took the plunge and ordered rounds three, five and seven. They even ordered two more beers for Michael Delaney and Alex Bentley when they joined them and the introductions were made.

The pilgrims dined well that evening in the Hotel St Jacques. Alex promised them even better fare the following night when the chef was going to cook them an Auvergne meal with some of the specialities of the region. The next day the pilgrims were to inspect the town and generally make themselves at home in France. The last little band of pilgrims, the ones from England, were to arrive in the morning.

The head waiter made his dispositions carefully the next evening. He sectioned off part of his dining room. The tables were reorganized so that one long table ran across in front of the kitchen entrance, flanked by two others. The tables were adorned with dark red candles and crisp white tablecloths and napkins. Three types of wine glasses were lined up to the side of each place setting. Bottles of white and red were placed at strategic intervals along the tables. Through a judicious use of sign language, acquired during his years of service with the French Army in North Africa, he managed to extract from Alex Bentley a seating plan for the occasion, name cards in Bentley’s immaculate copperplate adding formality to the scene.

From his position at the centre of the top table Michael Delaney surveyed his flock shortly after half past seven. There was just one empty space, a pilgrim who had not arrived to take up his station, praying in the cathedral perhaps, or fallen asleep in his room. They were sampling, suspiciously at first and then with growing delight, the chef’s amuse-bouches , tiny tasters of croutons with a lemon and garlic flavour topped with small pieces of pickled vegetable or dried fish. On Delaney’s right sat Father Kennedy, Alex Bentley to his left. He observed that Alex had mixed up the Irish and the Americans but left the English sitting in a group. Delaney had met them all that morning.

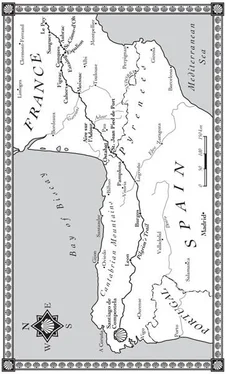

Sitting at the far end of the table to his left was a shifty-looking man of about thirty-five years with a small moustache and a greasy jacket. Girvan Connolly would have described himself as a merchant in his native quarters of north-west London. Others would have said he was something more than a stall-holder and something less than a shopkeeper. He dealt in things, pots and pans, wool, second-hand clothes, plates and knives and cups, buying them in bulk cheaply wherever he saw a bargain and trying to make a living off the profit. But business did not always go well for Girvan. Many of his suppliers had not been paid. Some of his customers found that the goods quite literally came apart in their hands. There were rumours that one or two of them were going to come and sort him out. In Kentish Town people knew what that meant. Free board and lodging for three months would be a godsend. So Connolly had pressed his remaining funds on his wife and fled. He doubted very much if his creditors would find him in Espalion or Figeac, Roncevalles or Burgos. He was on the run.

The great doors behind Delaney opened at this point and three steaming silver tureens of soup were carried in proudly by the waiters. It smelt of the countryside, of little farms up in the hills, of vegetables ripening under the sun. Alex Bentley had translated the details of the menu from the head waiter. He informed the company that this was known as Shepherd Soup. It had, he said, been cooked to this formula by shepherd mothers and shepherd wives for centuries up there in the vast desolate spaces of the Aubrac they would travel through in the coming days. From there it had passed into the culture of the wider Auvergne. The principal ingredients were the famous Le Puy lentils, flavoured with meat bones, carrots, turnips, swedes, local potatoes, a few chestnuts and whatever other delicacies the chef might have to hand. It went down very well with the dry white wine.

Beside Connolly, Delaney watched a forty-year-old Christian Brother in his black gown begin the attack on the soup. Brother White, Brother James White, taught Religion at one of the leading Catholic schools for boys in England. He felt the call to pilgrimage, as he had felt the call to join the Brothers all those years before. He knew he could do no other. He persuaded his abbot to give him leave of absence.

The waiters were clearing the empty plates now, filling up the glasses. Opposite Brother White was a prosperous gentleman of about fifty-five years, wearing a business suit with a flower in his buttonhole. He was quite short, and round, with a kindly face, looking as if he might be a sympathetic bank manager or a friendly headmaster. In fact, Stephen Lewis, a Delaney on his mother’s side, was the senior partner at Daniel and Lewis, the leading firm of solicitors in the little town of Frome in Somerset. His children were grown up. His wife was more interested in the garden than in routes of pilgrimage. Stephen Lewis had two reasons for coming on this journey. He had always been passionate about railway travel. He did not intend to dirty his expensive boots walking across the dusty roads of France and Spain. Bentley had fixed it so that he could travel most of the way by train, and they would, he knew, be different sorts of train. Stephen Lewis could have told you about the different gauges operating in the two countries, the different sorts of engines that would pull the passengers, the different bridges they would cross. He had the Baedeker Guide to European Train Travel by his bedside. Lewis’s second reason was much more irrational. He sold a lot of insurance policies in his office in Frome, looking out at the sluggish river and the dirty facade of the George Hotel where the stagecoach used to leave for London before the railways came. This pilgrimage was a form of insurance policy. It would, he felt, buy him a credit entry in God’s bank, a favourable note in the celestial account book that might mean that the days the Lord his God gave him here on earth would be long and healthy. Beside him was the empty seat, the name John Delaney standing out in Alex Bentley’s handwriting. The empty place troubled the pilgrims. It was as if there was a hole in the table, a gap left in a face where a malevolent tooth had just been extracted by the dentist.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death of a Pilgrim»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death of a Pilgrim» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death of a Pilgrim» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.