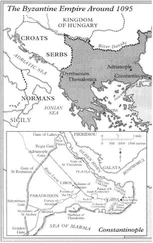

Tom Harper - Siege of Heaven

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tom Harper - Siege of Heaven» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Siege of Heaven

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Siege of Heaven: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Siege of Heaven»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Siege of Heaven — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Siege of Heaven», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I had seen enough: I crawled away, back down the slope to the hidden ledge where the Varangians waited. Even there, the screams from the mountaintop echoed down to us for hours afterwards — and still seemed to linger in the air long after we heard Godfrey’s men ride away. Only near sunset, when we were certain they had gone, did we rise from our hiding place and set out for Antioch.

7

A wall of death surrounded Antioch, far stronger than any ramparts of earth or stone, and a foul film hung above the city where the smoke of countless pyres stained the air. We marched along the river bank, barely an arrowshot from the walls, and saw no one. Only the dead were in evidence. The soft earth of the meadow outside the walls had been carved into innumerable graves, some marked with stones but most of them anonymous. One by one, each of the Varangians crossed himself, and then made a surreptitious sign against the evil eye for good measure. I laid a thin cloth over Sigurd’s face so he would not breathe the malignant air. We had carried him back from the monastery on a litter, and though he had gained some consciousness and could occasionally speak a few words, he was still achingly weak. Sweat glistened on his face where the fever boiled it out of him. It was shocking to see him diminished like this — like seeing an ancient oak tree felled for firewood. In the wandering course of my life I had not had to suffer the decline and death of my parents, for I had left them far behind in Illyria and never returned, but I imagined this was how a son must feel to see his father on his sick-bed: an indomitable constant brought down. It was strange, for he and I were the same age.

A few miles west of Antioch, in the hills between the plain and the coast, we found the hilltop where the remaining Varangians — and Anna — had moved their camp from the plague-ridden city. We climbed eagerly, our burdens suddenly much lightened. At the bottom of the valley, far below, I could see the sinuous course of the Orontes hastening towards the coast and the ship that would take me home. The setting sun turned the river gold, while an eagle wheeled silently in the sky above.

We came around a bend in the path and I knew at once something had changed. The guard who blocked our way was not a Varangian — indeed, he probably came from the opposite corner of the earth. His dark face was too wide and too short, like a reflection in a polished shield, with narrow eyes and a broad mouth that almost vanished under the mane of his beard. His helmet tapered to a sharp point like an onion, with a chain hood hanging down behind his neck, while the square plates of his scale armour rasped and chattered as they moved against each other. The long spear in his hands was angled across our path, though it was the horn-ended bow slung across his shoulder that was the real danger. He was a Patzinak, another of the emperor’s far-flung mercenary legions.

‘Who are you?’ he challenged us in guttural Greek.

‘Demetrios Askiates, with Sigurd Ragnarson and what remain of his men.’

The Patzinak nodded, without curiosity. ‘Come through. Nikephoros is impatient to meet you.’

Our fortunes had changed in the ten days we had been away. We had left the company with little more than the blankets they slept on; now, two enormous pavilions with gold-fringed awnings and crimson walls stood surrounded by neat rows of simpler tents. Guards, more Patzinaks, stood at every corner. Judging by the size of the encampment there must have been at least two hundred of them. An old orchard had become an enclosure for a dozen horses, all fine beasts branded with the mark of the imperial stables, while through an open door I saw a store tent piled high with casks of wine and sacks of grain. I had not seen anything so organised in months.

Among the throng of stocky, dark-skinned Patzinaks, I found one of the Varangians we had left to guard the camp.

‘What has happened here?’

The Varangian glanced anxiously at Sigurd’s litter. ‘The new ambassador came a week ago. What happened to you? Where are the others?’

‘The monk betrayed us. The others did not survive it — and Sigurd may yet follow. Where’s Anna?’

The Varangian’s mouth dropped open, as if the sun had fallen out of the sky. ‘Sigurd? Sigurd cannot die.’

‘I hope not. But where is Anna?’

‘Anna?’ Uncharacteristically, the Varangian seemed to be searching for delicate words. ‘She-’

A sharp voice behind me interrupted us. ‘Are you Demetrios Askiates?’

I turned. Another Patzinak, this one with a loaf-shaped cap and gilt edging on the plates of his armour, was watching me.

‘Nikephoros wants you.’

‘Find Anna and get Sigurd into her care,’ I told the Varangian. ‘Tell her I’ll find them afterwards.’

The confines of a former life seemed to rise up and envelop me as I stepped into the gilded pavilion. Ever since my superior, the general Tatikios, had departed Antioch in May, I had lived beyond the reach of the empire — a desperate, untamed life where we had slept rough, killed easily, and obeyed nothing but the dictates of survival and our duty to each other. Now the whole edifice of Byzantine civilisation, vast as the pillars of Ayia Sophia, seemed to have descended on the hilltop. Rich carpets traced designs of lions and eagles on the floor, echoing the mosaics of the great palace, while the silk walls of the tent glowed red, as if we stood inside the orb of a setting sun. Gossamer-thin curtains partitioned the different rooms, so that the slaves and clerks who scurried behind them became pale spectres of themselves. Mahogany trees held golden lamps in their branches, and icons of the saints looked out from their gilded windows. Rich incense filled the air. And, in the centre of the room, two men sat on carved chairs, their feet elevated on cushions, watching me carefully.

I had not changed my tunic or trimmed my beard in almost a fortnight of marching and fighting in the August sun. I had not washed, nor mended the tears and burns our ordeals had left in my clothing. In any company I would have felt filthy and disgusting: here, I felt like a dung-beetle rolling its ball on a banquet table. Too late, I remembered I should probably have bowed, though my back and my pride were both too stiff to allow it.

‘If you have been the emperor’s only representative these last four months, it is no wonder our situation is so desperate.’

The words were spoken with immaculate condescension, but their effect was like a kick in the groin. Fortunately, I was too weary to retaliate in anger. Instead, I looked blankly at the man who had addressed me. Both he and his companion were dressed in long white robes, trimmed with heavy embroidery and studded with coloured stones. There the similarity ended: the man on the left, who had spoken, was tall and strongly built; he kept his hair in studied disorder, and his face would have been handsome but for its arrogance. Only his beard seemed out of place, recently grown and not yet thickened to its fullness, like an adolescent who has not yet summoned the courage to shave, or a guilty man trying to hide his appearance. His companion, by contrast, was slight and clean-shaven, with thinning hair and a permanently worried expression tightening his soft features. I guessed he must be a eunuch. In their company you could believe that the courtyards and fountains of the palace were just beyond the door, not a thousand miles away across mountains and desert.

‘Has the emperor sent you?’ I asked.

The larger man drummed his fingers on the arm of his chair. ‘I am Nikephoros.’ He nodded to the eunuch beside him. ‘This is Phokas. We arrived from Constantinople a week ago. Where have you been?’

Evidently I did not merit pleasantries. ‘At the monastery of Ravendan, in the mountains north of here.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Siege of Heaven»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Siege of Heaven» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Siege of Heaven» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.