Sighing, he let his head drop for a moment, then dragged at the reins in his hand. He must get there before the exhaustion overtook him.

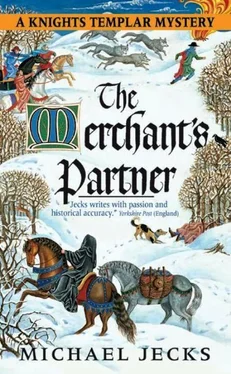

The snow had not dissipated in the least. As they trotted down the hillside towards the lane, it became clear to Simon that they would have as slow a struggle as they had endured earlier.

At first it looked like their worst fears were unwarranted. The lane that wound round before the house appeared relatively clear, and even as they rode farther up on to the top of the hill, it was still reasonably easy going. It was only when they began to descend once more that they found that the drifts had accumulated, and all at once they were bogged in snow which at times was over their feet as they sat on their horses. At one point Edgar showed his horsemanship, keeping his seat as his mount reared, whinnying in fear and disgust at the depth of the powder and trying to avoid the deepest drifts, and the servant was forced to tug the reins and pull the head round, to turn away from the obstacle. Standing and gentling the great creature, he glanced over at Baldwin.

“I think I’ll have to walk this one.”

He dropped from his saddle and, strolling ahead, spoke calmly to the horse as he led it forward, keeping a firm and steady pressure on the reins. Once it stopped and tried to refuse to carry on, shivering like a stunned rabbit, but then it accepted Edgar’s soft words of encouragement and continued.

That was the worst of it. Now the land opened up and the snow was less thick. There was hardly enough to rise more than a couple of inches above their horses’ hooves, and they all felt more confident, breaking into a steady, loping trot.

The house was soon visible. Simon could see it, a welcoming slab of grey in the whiteness all round, and he breathed a sigh of relief. He was about to make a comment, turning to look at Baldwin, when he saw a troubled frown on the knight’s face. He appeared to be staring at the ground near their feet.

“Baldwin? What’s the matter?”

“Look!” When Simon followed the direction of the pointing finger, he saw them. They were unmistakable, and his mind swiftly returned to the hunched figure of the dead merchant. The blood had been laid over the top of the snow, as if a geyser had spouted it up, and over the body the snow had been piled up into a makeshift hide-out. There had been little fresh powder over the body or the bloodstains. Trevellyn had died after the snowstorm had stopped.

And here were the clear marks, slightly marred by drifting, rounded and worn by the strong winds but still recognisable, of a pair of feet and the hoofprints of a horse, leading the way they were going. Back to the door of Harold Greencliff’s farm. Exchanging a look, the two men trotted on.

There was no doubt, the marks clearly led straight to the trodden mess in the ground before the door, the tracks of a horse and a man. Shaking his head, Baldwin tossed his reins to Edgar and sprang down. Simon followed, unconsciously testing the dagger at his waist, making sure that the blade would come free if needed. Noticing his movement, Baldwin smiled suddenly, and Simon saw that he had been doing the same with his sword. Leaving Edgar on his horse, they strode to the door, and Baldwin pounded heavily on the timbers with a gloved fist.

“Harold Greencliff! I want to speak with you. Come out!”

There was no answer. He thumped the door again, calling, but there was still no reply, and Simon suddenly found himself struck with a feeling of nervousness. He felt an extreme trepidation for what they might find inside. Involuntarily he stepped backwards.

“What is it?” snapped Baldwin, angry at being left outside. “God!” The sky was again starting to fill with tiny feathers of purest down, light specks of glistening beauty. But these minute granules were composed of pure coldness, and they could kill. Baldwin swore, then slammed his fist a last time on the door. ‘Greencliff!“

But there was no response. Glancing at Simon, he shrugged, then reached for the handle.

Inside it was almost as cold as out. Calling to Edgar to bring the horses in, Baldwin crossed the threshold and strode immediately for the hearth. Crouching, he studied the ash for a moment, then tugged off his glove and held his hand over it, swearing again. “Damn! We’ll need to light a fresh one!”

Simon busied himself gathering tinder and straw, then set to work relighting the fire. As he blew gently but firmly at the glowing sparks, carefully adding straw and twigs as the flames started to creep upwards, he was aware of Baldwin noisily clumping around the room, peering into dark corners and searching under blankets and boards. Meanwhile, Edgar unperturbably saw to the horses, removing their saddles and bringing their packs to the fire. Tossing them down, he gave Simon a quick grin before returning to the mounts.

The fire starting to shed a little light, he carefully piled smaller pieces of wood on top, then balanced logs above, and soon the house was beginning to fill with the homely smoke, catching in their throats, making them cough and rub at their eyes to clear away unshed tears. But as the fire caught hold the smoke rose to sit heavily in thick swathes in the rafters, and the air below cleared.

“He’s not here, that’s for certain,” Baldwin grumbled, crouching nearby.

“The footmarks seem to show that he was here last night,” said Simon calmly as he watched the flames. “Maybe he’s out to look after his sheep.”

Baldwin jerked his chin to point at the fire. “And left his fire to go out? In this weather? Come along, Simon. Nobody would let his fire die at this time of year. It could mean death.”

“Well…” Simon nodded slowly. ”If he’s gone, where has he gone to? We can’t follow now, not with the snow coming again, that would be too dangerous.“

“No, but I can take a look and see which direction he’s going in,” said the knight and stood. He walked outside, shutting the door behind him.

Already the weather had changed, and the small flakes were replaced by large petals falling at what looked like a ludicrously slow speed.

Peering, he narrowed his eyes as he tried to make out any marks in the snow. It was hard to see, the light was too diffuse behind the clouds, and with the failing light as day slipped towards night, he found that bending and looking for some differentiation in the contours was no help. All was uniformly white. There was not the relief of greys or blacks to mar the perfect apparent flatness. It was only when he stood again and stared farther away, wondering in which direction the youth would have gone, that he thought he could make out a depression left in the snow, like a shallow leat pointing arrow-straight to a mine. It led down the lane towards the trees, towards Wefford.

The wind began to build, whisking madly dancing flakes before his eyes, occasionally knocking them into his face. This was impossible, he thought. There was no way they could find out where the boy had gone in this: it was too heavy. He turned back to the door with a mixture of despondency and anger at being foiled.

The cry started as a low rumble on the Bourc’s right. He might easily have missed it, but his ears were too well attuned to sounds of danger, even after the punishment the wind had inflicted during the day, and he immediately stopped in his tracks and stared back the way he had come.

He could feel the shivering of the horses as the call began again. First low, then rising quickly to a loud howl before mournfully sliding down to a dismal wail of hunger: wolves!

Putting out his hand, he stroked his mount gently. There was no sign of them yet. They must be some distance away. He threw a quick glance at the hill ahead. The shelter it offered was a clear half-mile farther on. He gauged the remaining ground he must cover, then set his jaw and pulled at the reins, setting his face to the hill. It held the only possible cover here in this darkening land.

Читать дальше