As usual I have tried to be as historically accurate as is possible within the confines of a work of fiction. In 1320 the canonical church of Crediton was only recently completed, and Bishop Stapledon was very generous to it, giving the church two more fairs. Churches liked having fairs: roughly one-tenth of all profits went straight back to the priests, creating a pleasant windfall. In return the precentor of the church, together with his canons and vicars, was bound to celebrate Stapledon’s birthday throughout his life, and must solemnise the anniversary of his death. The Bishop also appointed four more young clerks to make sure the services were performed with suitable dignity, likewise St Lawrence’s Hospital in Crediton did exist, and it was serviced by a monk appointed from the convent at Houndeslow.

However, it is difficult to be accurate when describing real people. The Bishop himself was a highly important man in England. He contributed large sums to Exeter Cathedral, was involved with the Ordainers and helped create the Middle Party, founded Stapledon Hall in Oxford (now Exeter College), and began a grammar school in Exeter. Later he was to become Lord High Treasurer to the King, until murdered by the London mob in 1326. Yet as he appears in these pages his nature and character are entirely my own invention.

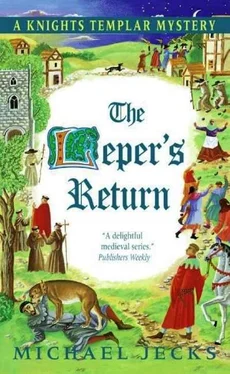

One other man in The Leper’s Return has the advantage of existing, and of being documented. He is Mr Thomas Orey, a fuller by trade, who was present at one of Bishop Stapledon’s services on the Wednesday before August 1 in 1315. The sudden recovery of his sight in the middle of the service led to the events described, although his chance meeting with John of Irelaunde was again the result of my overheated imagination. As for what actually happened to Thomas, I am afraid you must read on…

Michael Jecks

South Godstone,

February 1998

Walter Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter, watched the sky with a sense of foreboding, trying not to wince as his horse rocked gently beneath him.

“It looks like rain, doesn’t it, my Lord?”

The Bishop grunted non-committally. Those few words summed up the animosity with which people viewed the weather. During the disastrous years of 1315 and 1316, the crops had drowned in torrential rain and thousands had died in the ensuing famines. Few families across Europe had been untouched by the misery and even now, in autumn 1320, all feared a repeat of the disaster. Stapledon glanced sympathetically at his companion. “At least this year’s harvest was collected safely,” he said gravely. “God gave us a respite, whatever He may hold in store for the future.”

His companion nodded, but as he surveyed the pewter-colored clouds bunching overhead, his eyes held the expression of one who can see the arrow flying toward him and waits only to see where it will strike. “I pray that God will preserve us in the coming year as well.”

Stapledon forbore to comment. God’s will was beyond the understanding of ordinary men, and the Bishop was content to wait and see what He planned. At least this visit should be restful, he thought – away from the circle of devious, mendacious tricksters who surrounded King Edward.

The monk at his side, Ralph of Houndeslow, had arrived in Exeter only a few days before, asking for a room to rest for the night. When he had heard that the Bishop himself was about to depart for the large town of Crediton, northwest of Exeter, he had been delighted to accept Stapledon’s offer of a place in his retinue. It was safer to undertake a journey with company in these troubled times, even for a man wearing the tonsure.

Stapledon had found Ralph to be quite unlike previous visitors. Most who asked for hospitality at the Bishop’s gates were garrulous, for they were used to travelling, and delighted in talking about their adventures on the road, but Ralph was quiet. He appeared to be holding himself back, as though he was aware of the weighty responsibility that was about to fall upon his shoulders. Stapledon found him reserved and rather dull, a little too introspective, but that was hardly surprising. Ralph’s words about the weather demonstrated one line his thoughts were taking, but the prelate knew other things were giving him concern. It was as if a foul atmosphere had polluted the air in this benighted kingdom, and no one was unaware of the poison at work in their midst: treachery!

Stapledon turned in his saddle to survey the men behind. There were fifteen all told: five men-at-arms, four servants and the rest clerics. The troops were all hardened types recently hired to the Bishop’s service, and he viewed them askance. Since accepting his high office from the King and Parliament, it had been deemed prudent that he should have some protection, and after persuasion he had agreed to take on a bodyguard. He knew they were necessary for his safety, but that didn’t mean he had to enjoy their company. His only satisfaction was that when he studied them he could see they weren’t prey to fears for their future. They each knew that a mug of warmed, spiced ale waited for them at the end of their journey, and that was enough to assure their contentment. They were uneducated ruffians, and higher considerations were irrelevant to them. When he cast an eye over his servants, he saw that they weren’t plagued with doubts either, for they knew their jobs, and would blindly obey their master. No, it was only when he looked at his monks that he saw the weary anxiety.

Stapledon knew what lay at the bottom of it, and it wasn’t only the weather: the clerics, like himself, were aware that civil war was looming.

It was many years since the King’s grandfather, Henry III, had engaged Simon de Montfort in battles up and down the kingdom, but the horror of it was known to those who were educated and could read the chronicles. Their trepidation reflected that of all the King’s subjects as stories spread of the increasing tension between two of the most powerful men in the land. The Bishop paid no heed to such rumors – he had no need to. He had witnessed at first hand how relations between the King, Edward II, and the Earl of Lancaster had soured.

Earlier in the year, Sir Walter had become the Lord High Treasurer, the man who controlled the kingdom’s purse. In theory, the position was one of strength, but it made him feel as safe as a kitten dropped unprotected between two packs of loosed hunting dogs. No matter how he stood, he was constantly having to look to his back. There were many, in both the King’s party and the Earl’s, who would have liked to see him ruined. Men who had shunned him before now pretended to be his friend so that they could try to destroy him – or subvert him to their cause. Stapledon was used to the twisted and corrupt ways of politics and politicians, for he had been a key mover in the group which had tried to bring King Edward and the Earl of Lancaster to some sort of understanding, but the deceit and falseness of men who were well-born and supposedly chivalrous repelled him.

He had hoped that the Treaty of Leake would end the bitterness, but the underlying rivalries still existed. Stapledon was not the only man in the kingdom to be unpleasantly aware of the rising enmity. Lancaster was behaving with brazen insolence; not attending Parliament when summoned, and recklessly pursuing his own interests at the expense of the King’s. Stapledon had no doubt that if the Earl continued to flaunt his contempt for his liege, there would be war. And if that happened, the Bishop knew that the Scots would once more pour over the border. They had agreed to a truce last year, in 1319, but more recently there had been rumblings from the north. Since their success at Bannockburn and their capture of Berwick, the Scots had become more confident. Stapledon was glumly convinced that if the northern devils saw a means of dividing the English, they would seize it.

Читать дальше