John Roberts - The Tribune's curse

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Roberts - The Tribune's curse» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

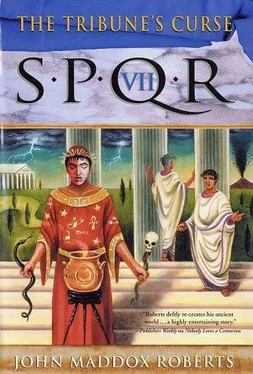

- Название:The Tribune's curse

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9780312304881

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Tribune's curse: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Tribune's curse»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Tribune's curse — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Tribune's curse», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And since Crassus was so roundly detested, why kill Ateius? Most of the men who opposed Crassus must have felt only delight at his discomfiture when his expedition was cursed. In the entire City, the only man I could think of who would kill Ateius for his actions was the younger Marcus Crassus, who keenly felt the insult to his family and had much to lose if his father’s war failed. He had expressed to me a quite reasonable and laudable desire to horsewhip Ateius as soon as he stepped down from office. Had he been concealing far-more-dire intentions? I rather doubted it. He had too much of his father’s unemotional, dispassionate nature. Still, I did not discount him as a possibility.

Then there was the curse, more specifically the Secret Name of Rome. Was Ateius murdered to protect the identity of the person who had divulged that name? This looked more promising. Also, it suggested a conspiracy. One thing I knew from long experience: it is easier to hide an elephant under the bed than it is to hide a conspiracy in Rome, especially one that involves not only important men, but foreigners like the sorcerers I had interviewed. Sometimes, it seems as if conspirators are actually eager to talk, if you can just give them an excuse.

I was beginning to get impatient with Bacchus when he tapped me with one of those inspirations: I had been concentrating on the cursed man and the murdered man, but suppose these were just minor casualties of an attack aimed at Rome itself? This seemed promising and got my patriotic, republican feathers ruffled. After all, the indignation over the curse was not because of its assault on Crassus, whom nobody liked, but because it endangered Rome. Orodes again? But the business of the curse seemed incredibly subtle for some long-sleeved, trousers-wearing barbarian tyrant. Unless, of course, he had the aid of a Roman traitor.

I realized that I was trying too hard to pin the blame on a foreign enemy. I did not want to believe that, once again, Romans were engaged in fratricidal, internal warfare. A will to believe or disbelieve something is the enemy of all rational thought.

Somehow, I knew that I was overlooking something. I was sure that there was a motivating factor that I was missing, as well as a unifying center, a sort of double nexus at which all the tangled strands of this maddening business crossed. I slammed my cup on the table in frustration.

“Is something wrong, Senator?” asked a plump young serving woman.

“I am receiving insufficient inspiration,” I told her.

“I thought maybe it was because your jug’s empty.”

I looked into the lees swirling in the bottom of the jug. “So it is. Well, that’s easily rectified. Bring me another.”

She took the empty and returned with a full jug. “I can’t promise inspiration, but the wine’s good.”

It may be that I was walking a trifle unsteadily when I made my way back through the Forum. Even for the greatest gossiping spot in the world, it was in something of an uproar. Self-appointed public orators were haranguing knots of idlers from the bases of monuments; people were babbling away as if they were actually well informed about the affairs of the world; senators stood around on the court platforms and the steps of the great public buildings, arguing vehemently about one thing or another.

“Decius Caecilius!” It was Cato, standing in the portico of the Temple of Castor and Pollux. He was with Sallustius Crispus, the hairy oaf I’d met at the baths a few days before. Just what I needed. The man who had been one of my least favorite Romans for many years was friendly with my latest object of dislike. Oh, well. After shaking Clodius’s hand in public the night before, I could smile my way through this.

“Any progress on the investigation?” Cato asked. He smelled like a wine cask, but then so did I. For a moment I wondered which investigation he meant, then I realized he might not know about the first.

“Things are coming along nicely,” I lied. “I was looking for Milo to make my report.”

“Have you heard the rumor that’s sweeping the City?” Sallustius said. “People have reported seeing the Furies right here in Rome!” He grinned, apparently proud of his bravery in speaking the name right out loud. “They are described as having the heads of hags with snakes for hair and long fangs, vulture bodies, huge claws, and tails like serpents.”

“I always knew they’d look just like the pictures on Greek vases,” I said.

“Word has it they came to destroy Ateius Capito for his sacrilege,” Sallust said.

“Asklepiodes says he’s been dead at least two days,” I told them. “Why are they still hanging about?”

“What I want to know is how such a rumor got started,” Cato said in ill temper. “As if people weren’t enough on edge already.”

“I’m sure I have no idea,” I told him, my second lie in as many minutes.

A lictor came up the steps and stopped in front of me, unshouldering his fasces . “Senator, the consul Pompey wishes to speak with you. Please come with me.”

“I am summoned,” I said. “Will you gentlemen excuse me?”

“Do not let us detain you,” said Cato.

Perhaps I should explain our ironic tone. In these days of the First Citizen, subservience is the rule, but back then Roman senators resented being summoned like the lackeys of an Oriental despot. A consul had the right to convene a meeting of the Senate, but he had no power over individual members of that body. We all chafed at Pompey’s high-handed methods, which may have resulted from his ignorance of constitutional forms. Pompey was, as I have said, a political lummox.

I followed the lictor to the temporary Grain Office established in the Temple of Concord. Here Pompey and his staff had their headquarters, and from here he amended and controlled the grain supply of Rome and all its possessions. We passed through a foyer where slaves, freedmen, and their supervisors went over the heaps of documents that arrived daily by special courier. These were sorted, reduced to manageable size, and reported to Pompey and his closest advisers. The messengers would be sent back out with orders for the many local Roman governors and purchasing agents all over the world. It was a formidably efficient organization.

We passed out onto a roofed terrace, and Pompey looked up from a broad, papyrus-strewn desk. “Ah, you found him. The rest of you, give us leave.” The other men filed out of the terrace like dismissed soldiers, and the two of us were alone.

“What progress, Senator?” Pompey asked. I told him what little I’d learned so far that day, and he shook his head in exasperation. “Whatever killed the wretch, I am sure it wasn’t some snaky-headed Greek harpy.”

“I believe the harpies are supposed to live above ground,” I said, “and while mischievous, are not so fearsome as the Friendly Ones. Prettier, too, if we’re to believe the paintings.”

“I know that. I am just not interested in tales to frighten children. I need somebody to throw to that mob before they get out of hand.” This was an uncommonly blunt statement, even for Pompey.

“I’ll have a name for you soon,” I said.

“Not unless you go easier on the wine.”

“It’s never interfered with my attention to duty,” I said, fuming. Bad enough to be summoned like a straying slave by this jumped-up soldier, but I had to listen to him berate me as well.

“Now, what about your other investigation?”

“Other investigation?” I said innocently.

“Yes,” he said impatiently, “the one that charges you to discover who betrayed the Secret Name of Rome.”

“Well, so much for the Pontifical College being able to keep a secret.”

“Are you serious? Three of the men at that meeting told me all about it within the hour.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Tribune's curse»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Tribune's curse» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Tribune's curse» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.