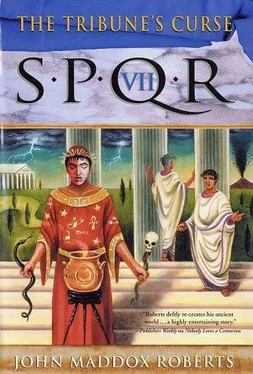

John Roberts - The Tribune's curse

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Roberts - The Tribune's curse» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Tribune's curse

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9780312304881

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Tribune's curse: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Tribune's curse»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Tribune's curse — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Tribune's curse», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“If you will come with me, Senator,” Demetrius said. I followed him into the musty warren of rooms beneath the temple proper. Aemilius had been a curule aedile, while the temple was the headquarters of the plebeian aediles, but the records of both were kept there.

“Since it was a recent year,” Demetrius said, “the records will be easy to find.”

I wasn’t looking forward to going over the documents in a tiny room by the smoky light of an oil lamp and was much relieved when the slave showed me to a room with a large, latticed window through which I could see the imposing superstructure of the Circus Maximus.

“I shall be back in a few minutes, Senator,” Demetrius said. He disappeared into an adjoining room, and I heard him giving instructions to some other slaves.

I sat at a long desk, groaning as my knees bent, all too aware that, if I sat too long, I would probably be unable to get up. Still, it was pleasant to sit there, listening to the clamor of the market below and the screeching axles of the chariots in the Circus, where the horses were being exercised. A few minutes of this, and Demetrius returned with a slave boy, each of them bearing a basket laden with papyrus scrolls and wooden tablets.

“Here they are, sir,” he announced. “All still in one place, luckily.”

“Would you happen to have a list of that year’s magistrates handy?” I asked him.

He turned to the slave boy. “Bring my writing kit and some scrap papyrus.” The boy went away, and I began arranging the documents on the table. When he returned, Demetrius took his reed pen and began writing down the names of the serving magistrates of the third previous year, neatly and from memory: consuls, praetors, aediles, tribunes, and quaestors. “Do you need the promagistrates serving outside of Rome?” he asked. “I’ll have to look some of them up.”

“No need,” I assured him. “I can see you’re going to be invaluable to me next year.”

“I look forward to it,” he said, apparently without irony. “Will there be anything else?”

“I don’t think so.”

“I will leave Hylas here with you. If you should need anything, he will see to it.”

I thanked him and set to work. The boy named Hylas sat on a bench. After a while I became aware that he was staring at me.

“What is it?” I asked.

The boy blushed. He appeared to be about twelve years old. “Excuse me, sir. Are you a charioteer?”

This was a new one. “Nothing so exalted, I am sorry to report. I am a mere senator. What causes me to resemble the racing gentry?”

“It’s just that, well, the only men I’ve ever seen bruised up like that are charioteers who’ve been in wrecks.”

“Am I that colorful?”

“The whole side of your neck and half your face are purple,” he reported.

“Sometimes,” I told him, “the gods are demanding. Now, I have work to do.”

Scanning the list of magistrates, I saw immediately the one name I knew I would find: Clodius. He was one of the tribunes, and the main reason I was out of Rome that year. He had been another busy man. Besides his scandalous legislation to distribute grain to the people free of charge (his promise to do so had secured him the election), he had worked furiously to get Cicero exiled, to get the proconsular provinces of Macedonia and Syria for the year’s consuls, and to do more besides. It seemed unlikely, however, that he would be concerned with the aediles’ persecutions of foreign cults.

The earliest dated document of the year was an instruction from the consul Piso to investigate and scourge from the City the Egyptian cults, which were distracting citizens from observance of the State religion and, more seriously, sucking money from Rome to Egypt.

Next, Aemilius Scaurus reported on the proliferation of Egyptian temples in Rome, in the surrounding municipia , and in Italian towns as far afield as Capua and Pompeii. Most of them were dedicated to the Isis cult. This caused me some amusement. Having spent some time in Egypt, I happened to know that the cult of Isis and Osiris was just about the dullest, most respectable religion imaginable. The whole College of Vestals could attend the Isis ceremonies for years without being exposed to the mildest impurity.

Now, the Egyptians had some truly scabrous cults, but they kept the good stuff at home, to themselves. What these guardians of public morals really needed was to attend one of the festivals of Min or Bes, gods who delivered their worshipers a good time.

Once the unfortunate followers of Isis had been dealt with, the aediles turned their attention to other cults and to magicians practicing solo. The tally of names looked like one of Sulla’s proscription lists, although they probably weren’t as profitable to those denouncing them. I thought it might be amusing to find out how many of these men were still practicing in the City. That would tell me how many had been able to bribe their way out of the ban.

I noted that most of the names were foreign. Some were Etruscan, many were Marsian, and the rest were Greek, Syrian, and so forth. I was willing to bet that many were ex-slaves with fake names and accents. For some reason, those who believe in magic are always ready to credit exotic foreigners with greater power in these matters than their own countrymen.

“Listen to these,” I said to young Hylas. “Hezzebaal the Paphlagonian, Chrysanthus of Thebes, Cinnamus of Lydia, Euscios the Arab, Ugbo the Wonder-Worker-Ugbo! What sort of name is that? It sounds like a dog gagging.”

“I’m afraid I don’t know, Senator. Sorry.”

“Don’t be. It’s what we educated people call a rhetorical question. It doesn’t call for an answer. Can you write?”

“Certainly, sir.”

“Excellent. I want you to copy this list of names for me while I study these other documents.”

The boy took the reed pen, and I gave him the scrap of papyrus with the list of magistrates. Carefully and with great concentration he began copying the names in a blocky, workmanlike hand. Like so many young slaves he had the name of one of the famous pretty boys of antiquity, but he wasn’t an especially attractive youth-not that my tastes run that way. He was snubnosed with protrudingupper teeth, but he seemed to be intelligent. I have always been willing to overlook ugliness in a slave if he has some redeeming quality.

“Be sure to copy the descriptions as well,” I admonished.

“I am doing that, sir,” he said dutifully. Next to each name were a few words describing the putative magician’s speciality: “necromancer,” “spirit medium,” “astrologer,” “summoner of Eastern gods,” and so forth. One was described, alarmingly, as “raiser of corpses.”

Besides these practitioners there were organized cults whose supposed indecent practices were catalogued in some detail. There were the usual ecstatic dancing, public fornication, self-mutilation, drug-induced intoxication, unnatural acts with animals, mass flagellation, and loud music. I have always objected to loud music myself.

I found a certain unworthy pleasure in reading about these supposedly disgraceful practices adjacent to that list of prominent public men. I was familiar with many of those men, and knew some of them to be addicted to things far worse than any attributed to the religious libertines. The difference was, they were senators while these cults attracted slaves, freedmen, the lowest of the proletarii , and the resident foreigners.

This is nothing new, of course. We are always anxious to protect the lower orders from vices that we ourselves practice with great enthusiasm. We know that we have the inner, philosophical strength to resist carrying our pleasures to excess, while the childlike masses are apt to be corrupted by them.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Tribune's curse»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Tribune's curse» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Tribune's curse» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.