John Roberts - The Tribune's curse

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Roberts - The Tribune's curse» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

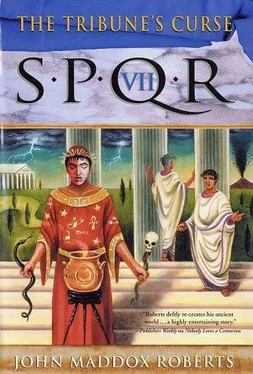

- Название:The Tribune's curse

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9780312304881

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Tribune's curse: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Tribune's curse»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Tribune's curse — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Tribune's curse», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Well, I must be going, Decius. Good luck.” He clapped me on the shoulder, raising a cloud of the fine chalk with which my toga had been whitened. It settled all over him, making him sneeze.

“Careful, there, Scipio,” I said. “People might think you’re standing for office, too.” He went off to his meeting, snorting and brushing at his clothes. This put me in an even more cheerful mood. Then I caught sight of a man I was far happier to see.

“Greetings, Decius Caecilius Metellus the Younger!” he shouted, striding toward me with a great mob of hard-looking clients behind him. His voice carried clear across the Forum, and people parted before him like water before the ram of a warship. Unlike Scipio he was accompanied by his lictors. By custom they were supposed to precede him and clear his way with their fasces , but it took a fleet-footed man to stay ahead of this particular magistrate.

“Greetings, Praetor Urbanus! ” I hailed. Titus Annius Milo and I were old friends, but here in public only his formal title would do. Starting as a street thug newly arrived from Ostia, he had somehow leapt ahead of me on the cursus honorum , and I never understood exactly how he did it. Whatever the means, nobody ever deserved the honor more. He was living proof that all you needed was citizenship to make something of yourself in Rome. It helped that he had energy to match his ambition, was awesomely capable, inhumanly strong, handsome as a god, and utterly ruthless.

He embraced me expertly, never actually touching me and thus saving himself from a chalking. His crowd of toughs made a ludicrous attempt at looking dignified and respectable. At least he kept them reined in out of respect for his office. He was the deadly enemy of Clodius, and everyone knew that in the next year, when neither of them held office, it would be open warfare in the streets of Rome.

“On your way to court?” I asked him.

“A full day’s schedule, I’m afraid,” he said ruefully. If there was one thing Milo hated, it was sitting still, even when he was doing something important. On the other hand, he had a trick of making everybody involved in a suit extremely uneasy with the way that, at intervals, he rose from his curule chair and paced back and forth across the width of the praetor’s platform, glaring at them all the while. It was just his way of working off his abundance of nervous energy, but he looked exactly like a Hyrcanian tiger pacing up and down in its cage before being turned loose on some poor wretch who got on the wrong side of the law.

“How are the renovations coming along?” I asked him.

“Almost finished,” he said, looking pained. He was married to Fausta, the daughter of Sulla’s old age and possibly the most willful, extravagant woman of her generation. For years Milo had lived in a minor fortress in the middle of his territory, and Fausta had made it her first order of marital business to transform it into a setting worthy of a lordly Cornelian and daughter of a Dictator.

“If you’d like to admire them,” he said, brightening, “we want you and Julia to come to dinner this evening.”

“I’d be delighted!” Not only did I enjoy his company, but Julia and Fausta were good friends as well. Plus, I was in no position to turn down a free meal. My share of the loot from Caesar’s early conquests in Gaul had made me comfortably well-off for the first time in my adult life, but that wealth would vanish without a trace in the next year, inevitably.

“Good, good. Caius Cassius will be there, and young Antonius, if he bothers to show up. He’s been with Gabinius in Syria, but there’s been a lull in the fighting, and he got bored and came home. He never stays still for long.”

He was referring, of course, to Marcus Antonius, one day to be notorious but back then known mainly as a leading light of Rome’s gilded youth, an uproarious, intemperate young man who was nonetheless intensely likable.

“It’s always fun when Antonius is there,” I said. “Who else?”

He waved a hand airily. “Whoever strikes my fancy today, and Fausta never consults me, so it could be anybody.” Milo never kept to the stuffy formality of exactly nine persons at dinner. Often as not, there were twenty or more around his table. He politicked tirelessly and was liable to invite anybody who might be of use to him. At least his was one house where I knew I would never run into Clodius.

“As long as it’s not Cato or anyone boring like that.”

Milo went off to his court, and I went back to my meeting-and-greeting routine. About noon things livened up when two Tribunes of the People ascended the rostra and began haranguing the crowd. Strictly speaking they were not supposed to do this except at a lawfully convened meeting of the Plebeian Assembly, but feelings were running high just then, and at such times the tribunes ignored proper form. Since they were sacrosanct, there was nothing anyone could do except yell back at them.

I was too far away to make out what they were saying, but I already knew the gist of it. Marcus Licinius Crassus, triumvir and by reputation the richest man in the world, was preparing to go to war against Parthia, and a number of the tribunes were very put out about the whole project. One reason was that the Parthians had done nothing to provoke such a war-not that being inoffensive had ever kept anyone safe from us before. Another was that Crassus was unthinkably rich, and a victorious war would make him even richer, and therefore more dangerous. But a lot of people just hated Crassus, and that was the best reason of all. The tribunes Gallus and Ateius were especially vehement in their denunciations of Crassus, and it was these two who bawled at the crowd in the Forum that day.

All their yowling was to no avail, naturally, because Crassus intended to pay for hiring, arming, and equipping his legions out of his own purse. He would make no demands on the Treasury, and there was nothing in Roman law to prevent a man from doing that, if he had the money, which Crassus did. So Crassus was going to get his war.

That was all right with me, as long as I didn’t have to go with him. Nobody objected, because they actually thought he might be defeated. In those days we thought little of the Parthians as fighting men. To us they were just more effete Orientals. Their ambassadors wore their hair long and scented; their faces were heavily rouged and their eyebrows painted on. As if that weren’t enough, they wore long sleeves. What more evidence did we need that they were a pack of effeminate degenerates?

The proposed war was so unpopular that recruiters were sometimes mobbed. Not that there was great recruiting activity in Rome. The citizenry by that time had grown woefully unwilling to serve in the legions. The smaller towns of Italy supplied more and more of our soldiers.

Caesar’s war in Gaul made no more sense, but it was immensely popular. His dispatches, which I had helped him write, were widely published and added luster to his name, and the plebs took his victories as their own. People liked Caesar, and they didn’t like Crassus. It was that simple.

The City was full of Crassi that year. Marcus Licinius Crassus Dives was, for the second time, holding the consulship with Pompey. His elder son, the younger Marcus, was standing for the quaestorship. So it was a great year for Crassus, despite the unpopularity of his proposed war. He and Pompey were being amazingly amicable for two men who hated each other so much. Crassus was insanely envious of Pompey’s military glory, and Pompey was similarly envious of Crassus’s legendary wealth.

Friction had been mounting between the members of the Big Three, but, the year before, Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus had met at Luca to iron out their differences, and all had been cooperation since. Crassus and Pompey agreed to extend Caesar’s command in Gaul beyond the already extraordinary five years, were raising more legions for him, and had given him permission to appoint ten legates of his own choosing. In return, Caesar’s people in the Senate and, more important, the Popular Assemblies would give Crassus his war and Pompey the proconsulship of Spain when he left office. Spain had become a rich money cow, peaceful enough in those years that Pompey wouldn’t actually have to go there but could let his legates handle the place and send him the money.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Tribune's curse»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Tribune's curse» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Tribune's curse» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.