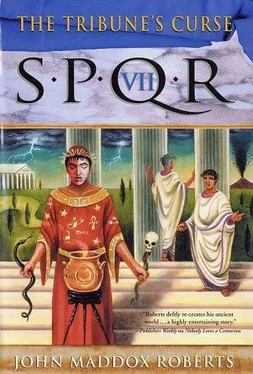

John Roberts - The Tribune's curse

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Roberts - The Tribune's curse» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Tribune's curse

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9780312304881

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Tribune's curse: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Tribune's curse»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Tribune's curse — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Tribune's curse», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Senator-”

“I think it would be most pleasing to the gods if we all did so, in fact,” Cato maintained stoutly.

“Senator!” Pompey snapped, out of patience. “We are losing time! If Cnaeus Pompeius Magnus,” here he poked a finger into his own chest, just in case Cato was in some doubt as to whom he meant, “twice consul, winner of more victories than any other general in Roman history, finds a military tunic the proper uniform for this ceremony, then a senator who has held no offices higher then quaestor and tribune should not find this beneath him!”

“Yes, Consul!” Cato said, with a fine, military salute. While his slaves helped him out of his gear, Pompey addressed the rest of us.

“The pacesetters will take the front position on each pole. These will be the praetor urbanus Titus Annius Milo and Lucius Cornelius Balbus, whom the Censors have just enrolled as a senator in recognition of his heroic military service. They are undoubtedly the two strongest men in this august, but usually out-of-shape, assembly.”

This was the first I’d heard that Balbus was a senator. There was an ancient tradition that heroism could win a man a seat in the curia and a stripe on his tunic, but Sulla had instituted the law that a man had to be elected to at least the quaestorship to be enrolled. But Pompey usually got what he wanted. It was one more piece of evidence that Sulla’s constitution was crumbling and that we were heading back into the anarchic old days.

The lictors positioned me on the left-hand pole, the one Milo captained. I noticed that Clodius was a few men behind me. I wished that he had been placed ahead of me, so that I could watch him suffer. It would have made up a bit for my own agony to come. Two other stalwarts took the rear positions, and we were all arranged.

“Now, Senators,” Pompey said, “I want no one to try to run, no matter how late it gets. We’ll never make it that way. We can get this done on time if we keep to a legionary quick pace. You’ve all been drilled in that since you were boys. Rome will rest on your shoulders today. So, lift!” Again came the word, hurled like a deadly missile, and we all stooped, laid hold of the poles, and lifted the tremendous parade float onto our shoulders. Upon the walls the people sighed with satisfaction. The animals seemed not to notice, merely blinking with lordly equanimity.

The flamines and other priests set out before us, some of them swinging censers in which incense burned. Atop the walls more incense smoked in braziers. We were burning enough that day to cause a serious shortage of incense throughout Roman territory.

“By the left,” Milo said quietly, “quick step, march .” As one man, we all stepped off, left foot first.

In the beginning, the weight seemed quite tolerable, but I knew that would change. Soon the older senators would start dropping out. Then fatigue would take its inexorable toll. And even among the younger senators, for years many had performed no exertion more strenuous than crawling from the cold bath to the hot. They would not last either. I wanted no part of Cato’s foolish nostalgia, but it seemed even to me that we were growing too soft. Unlike Cato and his ilk I did not blame this on foreign influence, but upon our increasing reliance on slaves to do everything for us.

The wall built centuries before by Servius Tullius had once marked out the boundaries of Rome. The City had long since spilled out of its confines, onto the Campus Martius and even across the river into the new Trans-Tiber district, and Sulla had even extended the span of the sacred pomerium , but these changes were too recent to make much of an impression. To all Romans of that day, the Servian Wall, following the line of the old pomerium , still defined the City.

Much building now lay outside the old wall, but it was surrounded by a span of sacred open ground on which nothing could be built and in which the dead could not be buried. This open ground formed our processional way. It was relatively level, going around the bases of the hills, and it was grassy, for no trees or shrubs were allowed to grow upon it. The old wall was still one of the military defenses of Rome, and you don’t just give your enemy effective cover.

We started out northeast along the base of the Capitol, circling the city to the right. All around us the temple musicians played their double flutes, striving mightily to drown any sound that might disturb the ceremony or be interpreted as an evil omen. Before we had made a half-circuit, I was sweating despite the crisp breeze. Others were in far worse condition. I heard gasping from the older men and from those less well-conditioned.

Between the Colline Gate and the Esquiline Gate, all the elderly senators stepped away from the litter. The weight on our shoulders grew fractionally heavier. When we reached the embankment where the river runs along the base of the wall, the middle-aged men were dropping out fast.

About an hour before noon we reached our starting point. Four hours for the first circuit. Here Pompey left us, red faced and puffing.

“Keep it up, men,” he gasped. “At this pace, we’ll finish before sundown handily.”

But there was more to it than time and pace. For the second circuit, we had perhaps half as many men to shoulder the burden. Granted it had been the weaker half that had left, but the willing backs of even old men had been a great help. By noon my shoulder was aching, and the sweat streamed off me by the bucketful. At least, to cheer myself up, I could always look back at Clodius, who was wheezing like a punctured bellows.

From atop the walls whole troops of little girls showered us with flower petals. They must have raided every garden and flower box in the City, and most of the petals were rather withered at that time of year, but we appreciated the gesture. All along our route, lesser priests and temple slaves dipped olive branches into jars of sacred, perfumed water and splashed it over us liberally, like the Circus attendants who dash water on the smoking chariot axles during the races. This we truly needed and appreciated, although ritual law demanded that we drink nothing during the ceremony.

We completed the second circuit of the wall by mid-afternoon, and some of us were in serious condition. My shoulder, neck, and back felt like molten bronze, and spots swam through my field of vision. My right arm was all but numb, my knees were shaky, and my feet were bleeding despite the hard marching I had been doing in Gaul. I was in better shape than 90 percent of those who were left. Clodius was in a near-coma, but still gamely on his feet. I no longer took delight in his discomfiture. Cato was hanging on stoutly to his Stoic demeanor, but I could see the signs of deathly fatigue in him. Milo and Balbus seemed not to be distressed, but neither was an ordinary mortal. Many of my colleagues would clearly not make it for another quarter-circuit, and I was having waking nightmares about the drugs wearing off and those huge animals setting up a struggle, rocking the litter.

“Good, men, good!” Pompey said as we set out on the third and final circuit of the walls. “Just one more little march, and it’s done! We will be here, ready for the sacrifice, when you return.”

“He’s assuming a lot,” wheezed somebody as we set off again.

“That’s Pompey,” said someone else in a phlegm-clogged voice, “always the optimist.”

“Save your breath,” Milo cautioned.

“Right,” Balbus said in his faintly accented Latin. “Now comes the hard part.”

And hard it was. Almost immediately, men dropped in their tracks, causing those behind to stumble and the float to lurch. Now I had another terror to add to the others. If the litter toppled, which way would it fall? The men on the wrong side would have a ton of wood and livestock fall upon them. But then, I thought, maybe that was what the gods wanted. A few squashed senators would make an impressive and, certainly, a unique sacrifice.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Tribune's curse»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Tribune's curse» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Tribune's curse» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.