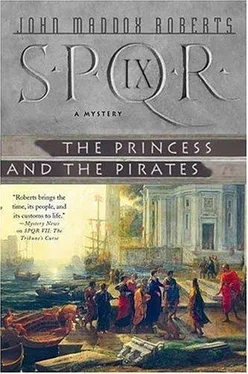

John Roberts - The Princess and the Pirates

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Roberts - The Princess and the Pirates» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Princess and the Pirates

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9780312337230

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Princess and the Pirates: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Princess and the Pirates»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Princess and the Pirates — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Princess and the Pirates», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I am not sleeping on any deck,” she said.

“The grain fleet sails for Egypt next month. Those ships are huge, and they have plenty of passenger space. They always stop at Cyprus before proceeding on to Alexandria.”

“And what will you be doing for a month?” she asked ominously. “Why, chasing pirates,” I answered, innocence oozing from every pore. Somehow, rumors of that German princess had reached her. We weren’t even married at the time, but that made little difference to Julia.

“Does your family have any hospitium connections in Cyprus? I’m sure mine don’t.”

“I doubt it,” I said, “but I’ll look through my tokens just in case. We have hospitia just about everywhere else in the Greek world, but I don’t believe any of my family have ever visited Cyprus. Of course, it’s the birthplace of your ancestress, so the place must be littered with your cousins.”

“I’ve warned you,” she said, ominously. The Caesars traced their descent from the goddess Venus who was, of course, born on Cyprus, just off the coast of Cyprus at any rate. Her uncle Caius Julius traded heavily on this supposed divine connection, to much mirth from the Romans. It infuriated Julia when I tweaked her for this bit of Caesarian bombast, but anything to get her mind off that German princess.

While she was busy with her preparations, I called in Hermes. He was just back from the ludus, where he trained with weapons most days. I was training him in all the skills of a politician’s assistant, which in those days included street brawling.

“Draft me a letter,” I ordered, and he sat at the desk, grumbling. With a fine career ahead of him, with freedom for himself and, perhaps, sons of his own in the Senate some day, he would have preferred the life of a common gladiator. He loved the fighting part, hated the writing. Well, there were days when I would have preferred a life in the ludus myself. At least there your only worry was surviving your next fight, and your enemy always struck from in front.

“To Titus Annius Milo from his friend Decius Caecilius Metellus the Younger, greetings,” I began. I saw Hermes’s eyebrows go up. He liked Milo. “I have been posted to Cyprus to chase pirates. I am a total dunce at sea and need your help desperately. Cyprus isn’t Gaul, which alone makes it a desirable place to be. There is a chance for some real money in this, and, besides, we’ll be away from our wives and have loads of fun.”

“I heard that!” Julia said, from deep in the house. The woman had ears like a fox.

“By the time you receive this,” I went on, “I will be on my way to Tarentum. If you have not arrived by the time I sail, I will leave orders that you are to have a fast Liburnian. I know you are bored to death in Lanuvium so don’t bother to pretend otherwise. We could both use some moderately safe excitement in agreeable surroundings. I look forward to seeing you in Tarentum or, failing that, on Cyprus.”

“Sea service?” Hermes said unhappily. He was even more nautiphobic than most Romans.

“Just a bit of coastal sailing,” I assured him. “We shouldn’t have to spend a single night at sea or ever sail out of sight of land. You’re an accomplished swimmer now; you’ll be perfectly safe.”

“I don’t mind the sea,” he said. “It’s being out on it in a ship I don’t like. The waves make me sick, storms can blow you to places where Ulysses never sailed, and even in good weather you’re in the middle of a bunch of sailors!”

“You’d rather go back to Gaul?” That silenced him. “Pack up.”

2

The trip to Cyprus is an easy sail when the weather is good, and ours was perfect. At Tarentum I had made a more than generous sacrifice to Neptune, and he must have been in an expansive mood because he repaid me handsomely.

From Italy’s easternmost cape we crossed the narrow strait to the coast of Greece, then south along that coast, stopping every evening at little ports, rarely straying more than a few hundred paces from shore. Even Hermes didn’t get seasick. We put in at Piraeus, and I took the long hike up to Athens and gawked at the sights for a few days. I have never understood how the Greeks built such beautiful cities and then could not govern them.

From Piraeus we sailed among the lovely, gemlike Greek islands, each of them looking as if it could be the home of Calypso or Circe. From the islands we crossed to the coast of Asia, then along the Cilician shore, keeping a close watch there for Cilicia was a homeland for pirates. From the southernmost coast of Cilicia we crossed to Cyprus, the longest stretch of open water on the voyage. Just as the mainland disappeared from view behind us, the heights of Cyprus appeared before us, and I breathed a little easier. I have never been able to abide the feeling of being at sea with no land in sight.

One reason that I dawdled was that Milo had not met me at Tarentum. I hoped that he was close behind and would catch up soon. I already had a feeling I was going to need him.

The problem was my flotilla, its sailors and marines, and my sailing master, one Ion. The deeper problem was that I was a Roman, and they were not.

For a Roman, service with the legions and service with the navy were as unalike as two military alternatives could possibly be. On land we were supremely confident, and over the centuries we had become specialists. Romans were heavy infantry. We held the center of the battle line and were renowned for feats of military engineering, such as bridge building, entrenchment, fortification, and siege craft. Roman soldiers, when they weren’t doing anything else, passed the time by building the finest roads in the world. For most other types of soldiery: cavalry, archers, slingers, and so forth, we usually hired foreigners. Even our light infantry were usually auxiliaries supplied by allied cities that lacked full citizenship.

At sea we were, so to speak, over our heads. Everyone knows how, in the wars with Carthage, we created a navy from nothing and defeated the world’s greatest naval power. The truth is, we accomplished this by ignoring maneuvers, instead grappling with their ships, thus transforming sea battles into land battles. We were still wretched sailors and kept losing entire fleets in storms that any real seafaring people would have seen coming in plenty of time to take action. And the Carthaginians repaid our presumption by raising the most brilliant general who ever lived: Hannibal. And don’t prattle to me about Alexander. Hannibal would have destroyed the little Macedonian dwarf as an afterthought. Alexander made his reputation fighting Persians, whom the whole world knows to be a wretched pack of slaves.

Anyway, our navy consists of hired foreigners under the command of Roman admirals and commodores. Most of them are Greeks, and that explains the greater part of my problems.

My first run-in with Ion occurred the moment I stepped aboard my lead Liburnian, the Nereid. The master, a crusty old salt dressed in the traditional blue tunic and cap, took my Senate credentials without a greeting or salute and scanned them with a barely repressed sneer. He handed them back.

“Just tell us where you want to go, and we’ll get you there,” he said. “Otherwise, keep out of the way, don’t try to give the men orders, don’t puke on the deck, and try not to fall overboard. We don’t try to save men who fall overboard. They belong to Neptune, and he’s a god we don’t like to offend.”

So I knocked him down, grasped him by the hair and belt, and pitched him into the water. “Don’t try to fish him out,” I told the sailors. “Neptune might not like it.” You have to let Greeks know who the master is right away or they’ll give you no end of trouble.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Princess and the Pirates»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Princess and the Pirates» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Princess and the Pirates» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Принцесса и пума [The Princess and the Puma]](/books/407345/o-genri-princessa-i-puma-the-princess-and-the-pum-thumb.webp)