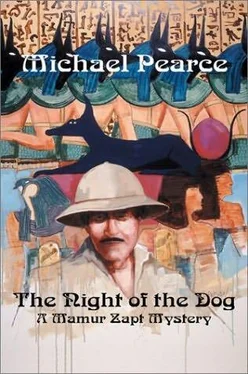

Michael Pearce - The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Pearce - The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Yussuf raised his hand threateningly. His sister, a woman of spirit, squared up to him. One of the orderlies, in defiance of the Prophet, began to lay bets.

Owen stepped in.

“Be off with you!” he said to the woman sternly. “Take this up at another time.”

He ushered her firmly towards the gate.

“I will speak to him,” he said to her when they had got out of earshot, “and see if I cannot resolve this matter.”

She went quietly enough. Owen admired her independence, but felt that reconciliation was more likely to be achieved in her absence.

Georgiades had asked Owen to meet him at a donkey-vous beside the Ezbekiya Gardens.

Owen liked the Ezbekiya, though gardens it was not. What it was was a dirty patch of fenced-off sand with a few straggly trees and occasional tufts of scrawny grass. In a land where, with a little water, anything would grow, and private gardens were a blaze of bougainvillaea and oleander, Cairo’s public gardens remained bits of desert, and the only colour in the Ezbekiya was provided once a week by the uniforms of the incredibly incompetent Egyptian regimental band. The Ezbekiya did indeed have its moments, in the very early morning when there were few people about and the big falcons sailed over it with their unexpectedly musical cries and the Egyptian doves cooed softly in the palm trees, but on the whole what Owen liked was the Ezbekiya’s outside.

All round the gardens were railings. And all along the railings were open-air stands, shops, stalls, restaurants, street-artists and tradesmen. Everything the ordinary Egyptian needed was there. The barber sat on the railings while his customers stood patiently in front of him to have their heads shaved. The tailor hung his creations on the railings. The hat-sellers marked off their territory with towers of tarbooshes, all fitting one on top of the other. The whip-makers plaited their whips through the railings and hung them from the trees.

There were trees all round the Ezbekiya, most of them comparatively young. Circular spaces about a yard wide had been cut in the pavement to receive them. To guard their roots the spaces were covered with gratings except for a few inches round the trunk. In this hole the chestnut-seller lit his fire, and on the gratings he set out his pans of roasted chestnuts. At night the coffee-sellers and the men who sold cups of hot sago brought their wares too; and all through the day there were sweet-sellers and nougat-sellers and nut-sellers and lemonade-sellers and tea-sellers and pie-sellers and cake-sellers-everything the sweet-toothed Egyptian might be persuaded to spend his little money on. Around each stall there were usually people talking, and the place which attracted the most conversationalists, after, perhaps, the pavement restaurants, was the donkey-vous.

This was the donkey-boys’ stand. The donkeys, the little white donkeys of Cairo, lay about in the road and on the pavement among the huge green stacks of berseem brought there for their dinner by forage camels. They were very rarely disturbed, at least by foreigners, since to hire a donkey cost a foreigner as much as a cab and pair of horses. But in their saddles of red brocade and their necklaces of silver thread with blue beads they looked very picturesque and the tourists loved to photograph them. For that, of course, they paid, and that, during the tourist season, was what the donkey-vous was all about. That, and conversation.

There was more than one donkey-vous in the Ezbekiya but Owen knew which one to make for. It was next to a postcard-seller, and to get to it you had to go past a row of very strange postcards stuck on the railings: views of Cairo, oleographs of Levantine saints, scenes of the Massacre of the Marmelukes and from the Great War of Independence, portraits of the Madonna and of St. Catherine, and, of course, hundreds of indecent photographs, very precise in some respects, strangely vague in others. At the end of the row, their backs turned to all these visual riches, was a ring of donkey-boys squatting on the ground. Among them was Georgiades.

He stood up when he saw Owen approaching.

“Here’s my friend,” he said to the donkey-boys. “I’ve got to go.”

He shook hands with several of the boys and exchanged farewell salaams with others.

“I wouldn’t mind a cup of something,” he said to Owen, so that the donkey-boys could hear, “and perhaps a bite or two. Have we got time?”

“Sure,” said Owen. “No hurry.”

They went over to the nearby tea-stall and then, with their glasses of tea, drifted over to one of the trees where a chestnut-seller was just lighting his fire. Georgiades peered into his basket.

“These look good ones,” he said to the man. “How about doing a handful for me and my friend?”

“It will take a moment or two,” the man said, “but it will be well worth the wait.”

Owen and Georgiades went a little way off and squatted down beneath the trees to wait. The sun had set and it was already quite dark in the gardens. Beneath the trees it was darker still.

As they sat there someone came up and, as was not unusual, joined them in their conversation. It was the boy they had talked to in the Coptic Place of the Dead, the one who had given them information-and kicked Georgiades on the shin.

“Kick me again,” said Georgiades, keeping his voice at the gentle, conversational level, “and I will kick your balls so hard that they will fly out of your backside.”

Even in the darkness Owen could see the boy’s teeth flash white in a big grin.

“That was good, wasn’t it?” he said with pride. “They didn’t suspect a thing.”

“It was good,” said Georgiades, “at my expense. However, we need not pursue this now. Ali wanted us to meet here,” he said to Owen, “so that we should not be seen by his little friends.”

“Your name is Ali, is it?” Owen asked the boy.

“Yes, effendi.”

“And your mother is Yussuf’s sister.”

“Yes, effendi,” said the boy, pleased that Owen had remembered. Relationships were important in Egyptian society. They conferred obligations. If a man was lucky enough to get a job it was expected that he would use his position to find jobs for others in his family or village. But they were also a guarantee. When a misdemeanour was committed, it was not the offender alone who was shamed but his whole family.

“Well, Ali,” said Owen, “you have helped us already and I am grateful. Help us again and you will not lose by it.”

“Unless they find out.”

“They will not find out.”

The boy was silent.

“Where do you want to begin?” Georgiades asked Owen.

“Let us go back to the Place of the Dead. That night. You saw the men and you told us whose men they were. What about the man who took the dog into the tomb? Whose man was he?”

“The same.”

“Are you sure?” asked Owen. “My friend”-he meant Georgiades-“he asked among the men and they say he was not one of them.”

“That is so,” said the boy.

“Then-”

“He follows the one I spoke of. But not him alone.”

“He follows another too?”

“He is a Zikr.”

Afterwards a lot of things fell into place. For the moment, though, Owen was so caught by surprise that he could only repeat foolishly: “A Zikr?”

“Yes. Do you not know the Zikr? They are dervishes who call upon the name of God. Also, sometimes, they dance.”

“I know the Zikr,” said Owen, recovering.

“Well, then. This man is a Zikr. But he goes to the holy one’s mosque.”

“Which mosque is that?”

“It is close to the Bab es Zuweyla.”

“The blue one?”

“Yes. The blue one.”

The Blue Mosque, which Owen had seen the previous day on his visit to the bazaars, was a dervish mosque, used almost exclusively by such as the Zikr.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Mamur Zapt and the Night of the Dog» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.