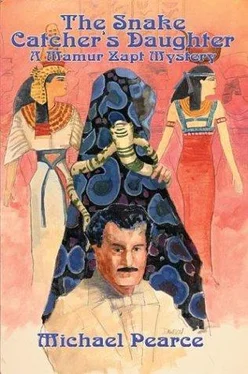

Michael Pearce - The Snake Catcher’s Daughter

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Pearce - The Snake Catcher’s Daughter» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Snake Catcher’s Daughter

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Snake Catcher’s Daughter: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Snake Catcher’s Daughter — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“That, I could understand,” he said softly, “although it was wrong; but why put him in the snake pit?”

“That was nothing to do with me.”

“Did you not give instructions?”

“No.”

“Who did?”

“I do not know.”

“Come,” said Owen, “the Bimbashi was in the inner courtyard, where there were only those who follow you. Would they have done this without your command?”

“It was done,” said the Aalima, “and I did not know it was done. I looked and saw that he was asleep and that was enough. I had my duties to think of.”

“Who commands in the courtyard?”

“No one commands,” said the Aalima. “We are women and at the Zzarr we are free people. Only at the Zzarr.”

“I cannot believe that it was done without your knowledge.”

The Aalima shrugged.

“I have told you truly,” she said.

“Very well. Again I shall believe you. But tell me now,” said Owen, “if you do not know, who would?”

The Aalima seemed genuinely to be thinking.

“Jalila?”

The Aalima gestured impatiently. “She merely carries the bowl.”

“She was out in the courtyard.”

“True, but… it would have had to have been someone else. She does not command enough respect.”

“She may have seen.”

“Others must have seen,” said the Aalima. “The chair was in the courtyard. But-”

“Yes?”

“They may have seen,” said the Aalima, “but I do not think they would have done it. He is a heavy man for women to carry. Especially that far into the Gamaliya. And who would have been willing to leave the ceremony?”

“Men?” suggested Owen.

“There were no men in the courtyard,” said the Aalima definitely, “apart from the Bimbashi. I will tell you what I will do,” she said. “I will ask my women. And then I will tell you.”

“Thank you,” said Owen, rising. “That is all I ask.”

As she was showing him out, he said to her: “Why the snake pit? Are snakes something to do with the Zzarr?”

“The only snakes at the Zzarr,” said the Aalima, “are men.”

Chapter 8

It was only half past ten and the city was already like an oven. Inside the offices it was even worse and Owen, eager as always to keep things in perspective, headed for the cafe. Just as he was about to sit down, he saw Mahmoud and waved to him to join him. Mahmoud, however, did not notice and went hurrying on past. Owen waved again and then went across to intercept him. Reluctantly, Mahmoud came to a stop.

His face had none of its usual alertness and vigour. It was pinched and withdrawn.

“Hello!” said Owen, recognizing the signs. “What’s up?”

“Nothing,” said Mahmoud. “Nothing.”

He tried to smile and failed, then began to edge away.

“Got something on,” he muttered.

“No you haven’t,” said Owen, putting his arm around him. Arabs were always putting their arms round each other. If you didn’t, you struck them as cold and unfriendly.

“Coffee,” said Owen. “Come on!”

He shepherded Mahmoud back to his table. Mahmoud allowed himself to be persuaded but looked at Owen without any light in his eyes. Indeed, he seemed almost hostile.

“What’s the trouble?” said Owen.

“Nothing,” said Mahmoud coldly.

“I know you too well to believe that,” said Owen.

The waiter, unusually, came quickly with the coffee. Mahmoud took a sip which was almost like a spit.

“Do you?” he said. “Do you?”

Owen laid his hand on Mahmoud’s arm.

“Come on,” he said, “what’s the matter?”

Mahmoud sat huddled and silent. When he was like this he was peculiarly exasperating. Normally he was so full of bounce that a chair could hardly contain him. On occasion, though, he swung to the other extreme, crumpling into apathy and lifelessness. You might have thought he suffered from some polarizing or cyclical illness; but the Arabs were all like this. They either burned with exhilaration or collapsed into the dumps; not like the stable British, who remained puddingy throughout.

They had been talking in French. Now Owen switched to the more intimate Arabic.

“If my brother is troubled,” he said, “then I am troubled. And if he does not tell me his trouble, so that I can share it, then I am doubly troubled.”

Mahmoud said nothing for some time. When he replied, however, it was in Arabic, which was a kind of response. “You cannot share,” he said, “because you cannot feel.”

“That is unjust,” said Owen quietly.

Mahmoud shifted uncomfortably.

“It is not your fault,” he said. “It is because you are an Englishman.”

Oh no, thought Owen, so that’s what it is.

“Have you forgotten so soon?” he said reproachfully. “I am not an Englishman.”

Something stirred down in the dumps. Arab, Mahmoud might be, and liable to plunge into the trough of depression; but Arab, he still was, and unable to forgive himself for anything that seemed a breach of courtesy. He raised a hand apologetically.

“I am not always clear,” he said, “about the difference between an Englishman and a Welshman.”

“This is fighting talk,” said Owen.

Mahmoud managed something that was a little like a smile. He took a sip of coffee, looked at it with surprise and took another sip.

“What have we done this time?” asked Owen.

“We? I thought you were a Welshman?” said Mahmoud, beginning to sparkle.

“We have a pact with them.”

“If you have, it’s a pact with the devil.”

“Are things that bad?”

“Well-”

Mahmoud looked round and waved for more coffee. He was beginning to brisk up. That was a good sign. Mahmoud, in normal form, had all the briskness and sharpness of a mongoose.

“They won’t give me access,” he said.

“Access?”

“To the files. It is quite improper. To refuse a request from the Ministry of Justice, from the Government. Whose country do they think this is?”

“Hold on. Whose files are we talking about?”

“Garvin’s, Wainwright’s, Mustapha Mir’s. Yours.”

“I haven’t refused you access.”

“Haven’t you?”

“I’m still thinking about it.”

“It’s not going to be up to you. An in-principle decision has been taken. By the Consul-General.”

“I’ll have a word with Paul.”

“It’ll be no good. This goes deep, you see. It raises big questions. The biggest,” said Mahmoud bitterly, “is: who governs this country? And we know the answer to that, don’t we?” Owen tried to think what to say. Mahmoud, however, was not expecting a reply.

“It’s the principle of the thing,” he said vehemently. “It is fundamental to the administration of justice. The investigating officer must have access to relevant documents. No one, no one should be able to refuse. No one should be above the law. Neither I nor you, nor the Khedive, nor the British. We are all equal before the law. Everyone! That is what justice is.”

“Yes,” said Owen, “but this is Egypt.”

“It doesn’t matter. It should make no difference.”

“It is the difference,” said Owen, “between an ideal and reality.”

“Yes, but,” said Mahmoud, all excited now, “on this there must be no compromise. Or where shall we be? One law for one, one for another”-forgetting that in Egypt there were at least three legal systems-“No!” He banged his fist on the table. The cups jumped. Owen looked around apprehensively; but other people, all over the place, seemed to be banging their fists too. It was the normal mode of Arab conversation. They were probably talking about something as innocuous as the weather. “We cannot have it!” shouted Mahmoud. “Not as Egyptians, no, nor as English, but as part of mankind! It is our right!”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.