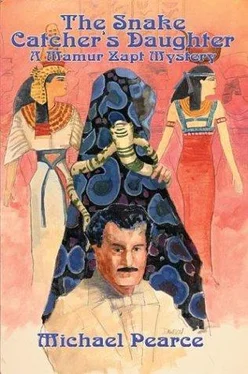

Michael Pearce - The Snake Catcher’s Daughter

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Pearce - The Snake Catcher’s Daughter» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Snake Catcher’s Daughter

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Snake Catcher’s Daughter: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Snake Catcher’s Daughter — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Garvin was, then, a formidable operator. He knew Egypt from top to bottom; and behind the frank, open face and the honest blue eyes was a political mind of no mean order. He played bridge regularly with the Consul-General and the Financial Secretary. Garvin was a great card player.

If there was a plot against him, the plotters would have their work cut out. The Administration would close ranks around Garvin in a way that Owen knew they would not close around him. He was not a member of the magic circle. He had not been to Cambridge. His father had died young and his family had been too poor to do other than secure him a commission in the army. He was, too, a Welshman; slightly suspect even in the army.

He was the magic circle’s servant, no closer to them, in the end, than he was to the Khedive. But they would expect him to protect Garvin. Certain things did not need to be spoken. He knew what the job was that he was being told to do.

In fact, he did not expect that to put much of a strain on him. Garvin, for all his faults, was honest. This would be a trumped-up charge, if charge it came to. It would be a political manoeuvre. Garvin, in any case, probably was not so much the object as a means: a means of hitting at the British Administration itself.

Owen sighed. He could see himself being forced to take sides. It was a thing he did not like, something he tried to avoid. Usually he got round it by interpreting his loyalty as to Egypt as a whole. There was a sense, a very real sense, as a matter of fact, in which the Khedive and the British Administration together formed the Government of Egypt. His loyalty was to that mystic concept; very mystic, he sometimes felt.

There was, though, a less mystic consideration. In a complex political game the outcome might require sacrifices. He could not see the magic circle going so far as to be ready to sacrifice one of themselves. They would be far more likely to sacrifice someone else; say, him.

Owen thought he had better take up card playing.

Garvin turned to him.

“I gather you know the situation,” he said.

Owen nodded.

“In general terms,” he said.

Garvin came back to his desk.

“Well, you’ll be raking over the details later,” he said. “That’ll be the job of the investigation. The question is, though, what’s the procedure to be?”

“The Parquet will be responsible, presumably.”

The Parquet, or Department of Prosecutions of the Ministry of Justice, was responsible for carrying out all investigations. The police merely reported a crime. A lawyer from the Parquet was then at once assigned to it and he was thenceforth responsible for investigating the circumstances, compiling the evidence, taking a view, and then, if the view was in favour of prosecution, presenting the case, as in the French judicial system, which the Egyptian closely resembled, to the appropriate court.

“Yes,” said Garvin, “but if they get that far it will go to the Mixed Courts.”

The Mixed Courts were a feature unique to the Egyptian judicial system. Where cases involved foreigners, they were heard not by the native courts of law but by a court on which sat judicial representatives from the foreigner’s own native country as well as the Egyptian judges.

“That being so,” said Garvin, “and, considering that one of the people involved is a senior member of the British Administration-me-it would seem desirable that a representative of the British Administration was attached to the case from the outset. Then, if it came to prosecution, the case that was presented would have the support of both countries.”

“Quite,” said Owen. “If it came to that. But will the Parquet agree?”

“You must be joking!” said Paul in the bar that evening. “The most they’ll agree to, with their arms twisted high up behind their backs and the army indicating that it’s about to come out on manoeuvres, is to the attachment of an observer.”

“That’ll do,” said Owen.

“It will have to,” said Paul. “Though it’s not at all the same thing. The observer just observes. He doesn’t join in the presentation of the case. Nor in the decision as to whether the case is to be presented. He can stick his oar in when it actually comes to the court but only as a secondary witness. The Old Man’s not happy about that but it’s as much as we’ve been able to get.”

“Do they genuinely want a conviction?”

“Probably not. They almost certainly know there’s nothing to convict. What they’re looking for, I suspect, is the publicity of its coming to court. It makes the British look bad to the outside world and it makes them look good to their own supporters.”

“It won’t make them look so good if the case is a real shambles.”

Paul smiled.

“We’ve already tried that,” he said. “I tried to get them to appoint some real duds to carry out the investigation, the likes of Mohammed Isbi. Said how greatly we respected his judgement, how much he had our confidence. Any case presented by him would be sure to have our support.”

“Well?”

“They wouldn’t wear it, of course. They’re not that daft. They know he’s as thick as a post.”

“So who have they appointed?”

“Their best and brightest. Mahmoud.”

Mahmoud el Zaki was one of Owen’s oldest friends. The two were actually very much alike, young men on the rise. They had met on one of Owen’s earliest cases, which had turned out to be one of Mahmoud’s first cases, too, and since then their careers had kept a parallel course. They were both self-sufficient, not exactly loners-Owen was quite gregarious-but standing a little apart from their fellows.

They were both to a certain extent outsiders: Owen because he stood outside the charmed circle of those who had been to public school and the ancient universities, and because of the ambiguity of the post of Mamur Zapt, responsible to the Egyptian and British Administrations; Mahmoud because he, too, was not by birth a member of the Egyptian elite. His father, a first generation graduate and, like Mahmoud himself, a lawyer, had died young while establishing a position and Mahmoud had inherited both the family’s expectations and its lack of wealth and social connections. He had had to work hard to rise, to do it all himself. There was quite a lot in common between him and the Welsh grammar school boy from an impoverished Anglican family; not least a tendency to define for oneself a social identity by siding with the suppressed Nationalist opposition.

Mahmoud was in fact formally a member of the new Nationalist Party, which did him no harm in the Parquet but which left him politically and socially uneasy when it came to encounters with representatives of the Egyptian elite. He was, for example, completely at sea when it came to talking to Zeinab. This was, however, only partly because she was the daughter of a Pasha. Like most educated young Egyptians, Mahmoud had hardly ever met a respectable young woman and did not know exactly how one should behave. Besides, he wasn’t completely sure that Zeinab was respectable and when they met usually finished up looking down between her feet with embarrassment.

He and Owen were sufficiently close for Owen to be able to ring him up and say: “Hey, about this Garvin business; can we have a talk?”

“Yes, yes!” cried Mahmoud at once. “Come right over!” Then he thought again. “Um, well, perhaps you’d better not. Not here, at any rate.”

“Lunch? Marsalis?”

“Yes, yes!” said Mahmoud, eager to make amends. “Today! This afternoon!”

“Right, then. One o’clock.”

One o’clock found him in a little street just off the Mouski, far enough down to be away from the clangs of the trams in the Ataba-el-Khadra, not so far down as to be completely within the purview of the old part of the city where the cafes tended to be pavement ones and you squatted on your haunches around a large tray on the ground and dipped your bread in; all very well, but not good for weighty conversation.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Snake Catcher’s Daughter» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.