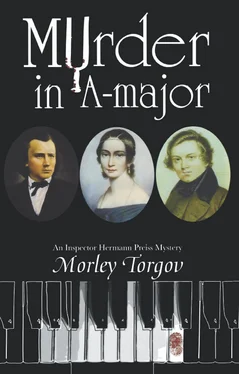

Morley Torgov - Murder in A-Major

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Morley Torgov - Murder in A-Major» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Murder in A-Major

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Murder in A-Major: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Murder in A-Major»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Murder in A-Major — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Murder in A-Major», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The remaining half of the concert would be taken up with a performance of Schumann's Fourth Symphony in D Minor. Before the Maestro took the podium, I had a minute or two to study the program notes which, at first glance, were somewhat confusing. It seemed that Schumann's Fourth was really his Second, according to the notes, having been composed as the second of his four symphonies in 1841. The composer, however, had been dissatisfied with the original version and revised it ten years later. As a result, the version we would hear this night was a musical rebirth occurring in 1851 after his Third Symphony, which was why it was now given the number “Four”.

There was something so haphazard about the creative process, especially in the musical field. So much seemed to depend upon impulse, inspirational moments that suddenly flashed then went dark, like the passage of fireflies in the night. How different from my world. In my profession, one necessarily piled fact upon fact upon fact, like constructing a brick wall. My world was one of logical sequences: two was followed by three which was followed by four. Anything different was unthinkable.

The D Minor opened with the strings of the orchestra sighing with a hint of yearning, suggesting autumn and the fading away of another year in the composer's life. The second movement, coming without a pause, began with a plaintive melody played by the oboe at a melancholy pace. Again without a break, the third movement, a boisterous scherzo, followed and promised to lift the dark mood left by the preceding two movements. For the first several bars, the musicians and conductor were as one, and the man on the podium waving his baton with such decisiveness seemed to be enjoying himself immensely.

But then, suddenly and for no apparent reason, Schumann let his baton drop to his side, where it remained for several bars. The Düsseldorf orchestra carried on bravely, the musicians no doubt expecting their leader to resume conducting as vigorously as before. Instead, when Schumann's arm rose once again, his beat was out of time to the music, and the baton moved back and forth in a desultory fashion. Moments later the Maestro seemed to recover; then his beat faltered again. By now the players were exchanging anxious glances. In the house, people were whispering. Even the most untrained ear could tell that the scherzo was disintegrating into a sorry jumble of sound. Somehow the orchestra, with no help from its conductor, managed to complete the third movement.

Eventually, the scherzo folded directly into a fast and brilliant finale. How the musicians managed this transition on their own was beyond explanation but, as suddenly as Schumann's attention had slackened earlier, it had revived and was sustained for most of the final movement.

Then it happened again. The unexpected fall of the baton, the lifeless dropping of his right arm. The remaining few minutes of Schumann's Fourth were played out in a state of disarray, the musicians ending their mission like troops caught up in a rout. What should have been an ovation instead became a moment of stunned silence. Without so much as a glance at the audience, Schumann fled the stage, leaving in his wake a smattering of polite applause and a sea of confused faces.

Going against the tide of people making their way to the exits at the rear of the auditorium, I advanced to the stage and made my way to the private lounge backstage reserved for the orchestra's conductor. As I approached, I could hear a commotion and recognized several of the voices, the most prominent being the voices of Robert and Clara.

“I am a ruined man…ruined!” Schumann was wailing.

“Calm yourself, Robert…please, try to calm yourself…everything will be all right…Dr. Hellman is here…” That was the voice of Clara Schumann.

Entering the conductor's rooms, I found Schumann sprawled on a sofa, his jacket removed, shirt collar unbuttoned, bow tie undone, legs and arms limp like those of an unstrung puppet. A bearded man in evening clothes hovered over the distraught composer, urging him to drink a milky liquid that he was offering in a small glass. I took the man to be Dr. Hellman, and the substance in the glass some form of sedative. “Please,” the bearded man pleaded, “just take this, Dr. Schumann, and I promise you-”

But Schumann's lips tightened like a vise; he would have none of it.

Close by the physician stood another person who was not at all familiar to me but who appeared to be as concerned as the others and spoke solicitously to Schumann, urging him to heed the doctor's advice and drink the potion. He was young, perhaps about twenty years of age, dressed in street clothes rather than formal eveningwear, and remarkably handsome. His full head of blond hair was brushed back off a high brow so that it almost touched his broad shoulders. His eyes were large and the shade of blue that reminded one of those clear clean lakes in Bavaria's mountain country. Had I spotted him on a sporting field, I would have judged him to be an athlete, given his slim but sturdy build and youthful voice. Though he and I exchanged quick glances, neither of us was inclined under the circumstances to engage in introductions, and I assumed that he was probably either a member of the concert hall staff or possibly a conservatory student who happened to be a family friend of the Schumanns, and left it at that.

Looking beyond his wife, Dr. Hellman, and another whom I recognized as Julius Tausch, the orchestra's assistant conductor, Schumann caught sight of me. “Preiss, thank God you're here!” he said, weakly beckoning me to come nearer and stand at his side. Ignoring everyone else, he addressed me as though I were his sole source of refuge. “You see, Preiss, you see, don't you? The ‘A’ sound? Even on stage when I am conducting, it pours through me like molten metal. They are killing me, Preiss. You must help me, save me!”

As he spoke these words, I happened to glance at Clara Schumann. She was staring at me coldly, as though defying me to respond to her husband's plea. I confess to a fleeting hesitation on my part. It was not easy to ignore the look of hostility on the woman's face. Nor was I eager to antagonize her. Indeed, I'd hoped that she and I would somehow join forces in rescuing her husband from whatever danger was threatening his life.

To Schumann, I said, “You have my assurance, Maestro, that I will do everything in my power to help you. You have my word, sir.” And with that, I turned to leave.

“Inspector…a moment, please-”

It was Clara Schumann. She had followed me down the corridor that led to the exit.

“Yes, Madam Schumann?”

“You see what is happening, don't you?” she said. “Your presence serves only to reinforce and even inflame my poor husband's illusions. If you truly wish to be of assistance to us, remove yourself from this matter entirely. Tonight. This very minute. I implore you.”

“And if I find that I cannot?”

Her expression froze. Without another word, she turned and made her way back to the conductor's lounge.

About one thing, at least, there was no mystery now: she and I seemed destined to carry on not as allies but as adversaries.

Not surprisingly, the local music critics were in complete agreement in the next morning's papers.

“Once again,” wrote one, “Dr. Schumann's lyric gifts show strong evidence of having faded…at best his music merely displays a sense of organization…”

Another opined that the composer “has so little talent for beautiful orchestral sound and apparently no use for it in any event…”

A third critic was even more vicious. “Absent were brilliant debates between different parts of the orchestra such as one finds in the works of Beethoven and Schubert; rather the music emerges in a grey and viscous mass of sound out of which occasional melodies seep…”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Murder in A-Major»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Murder in A-Major» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Murder in A-Major» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.