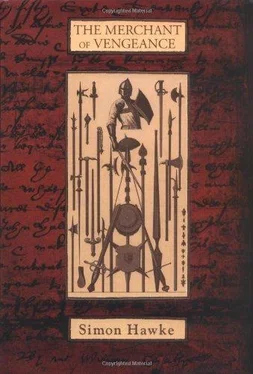

Simon Hawke - The Merchant of Vengeance

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Simon Hawke - The Merchant of Vengeance» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Merchant of Vengeance

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Merchant of Vengeance: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Merchant of Vengeance»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Merchant of Vengeance — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Merchant of Vengeance», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Shakespeare stared at him squinty-eyed for a moment, then flatly said, “There is no flask.”

“Why, you saucy, timorous, and motley-minded liar!” Smythe said. “What will you wager that if I picked you up and shook you, one should not fall out from somewhere within your doublet?”

“You would never dare!”

“Oh, would I not!”

Smythe reached out quickly and spun him around, then seized him about the waist from behind and easily lifted him up into the air.

“Gadzooks! Put me down, you great baboon! Have you lost your senses?”

Then Shakespeare yelped as Smythe turned him upside down and shifted his grip so that one hand grasped each of his ankles. “Now,” Smythe said, “what shall I do, I wonder? Shake you or make a wish?”

“Tuck! Damn you for a venomous double-dealing rogue, let me down at once, I say!”

“Hmmm, now what was it you said just now?” asked Smythe, holding him aloft. “There is no flask, eh? Was that what you said?” He started shaking the helpless poet up and down.

“Tuuuuuuuuuuck!”

Something fell out of Shakespeare’s doublet and struck the damp ground with a soft thud.

‘Well, now!“ said Smythe, ”what have we here?“ He turned slightly so that Shakespeare, still held upside down, could see what was lying on the ground.

“Is that a flask, or do mine eyes deceive me?”

“Ohhhhh, I am going to beat you with a stick!” said Shakespeare through gritted teeth as he vainly tried to strike out behind him. Smythe merely held him out farther away, at arm’s length.

“Aye, I do believe that is a flask I see down there at my feet. I do not suppose ‘twould happen to be yours, by any chance?”

“God’s body! You are as strong as a bloody ox!” said Shakespeare. “Let me down, I pray you, the blood is rushing to my head.”

Smythe released him. “Very well, then. Down you go.”

It was not very far to fall, no more than a foot or so, but from the way Shakespeare cried out, it might have been a precipice that he was dropped from. He fell to the ground in a heap, groaning.

“Now then,” Smythe said, looking down at him with his hands upon his hips, “what was it you were saying about not taking seriously anyone who drank?”

“You know very well what I meant, you great, infernal oaf,” grumbled Shakespeare, getting up and dusting himself off. “There is a deal of difference between a man who drinks in moderation and a man who drinks to excess.”

“Moderation?” Smythe replied. “Compared to you, half the drunks in London drink. in moderation, and the other half are bloody well abstemious!”

“Gentlemen,” a deep voice said from behind them, “if the two of you are intent upon a brawl, might I suggest a tavern, or perhaps some wooded place where you could maul each other to your hearts’ content?”

They turned to see a tall, gray-bearded, and barrel-chested man with sharp, angular features and thick, shoulder-length gray hair standing between them and the front entrance to the Locke house. In his right hand, he held a stout quarter-staff with one end resting lightly on the ground. “Either way,” he continued, “I would much prefer that you conduct your mischief elsewhere, and not at my front door, if you please.”

“Master Charles Locke, I presume?” Smythe said. He started toward him, but immediately stopped when he saw Locke raise the quarter-staff and hold it across his body in the defensive posture of a man who was prepared to fight.

“Who are you?” Locke demanded, gazing at him suspiciously. “What do you want?”

Smythe held out his hands, palms forward. “Your pardon, good sir, we mean you no harm. My friend and I were merely having a bit of sport, is all. As it happens, ‘tis you we came to see. My name is Tuck Smythe, and this is my friend Will Shakespeare.”

Locke frowned and maintained his staff held at the ready. “I know you not. What is it you want of me?”

“‘Tis a matter concerning your son,” said Shakespeare.

“Thomas?” Locke said, narrowing his eyes. “‘What have you to do with him?”

“In truth, not a very great deal,” Smythe replied. “We have met him for the first time but this afternoon, at the shop of our good friend Ben Dickens, the armourer.”

“I know of him,” said Locke curtly. “And yet I still know naught of you.”

“We are players, good sir,” said Shakespeare, “at present with the august company of Lord Strange’s Men.”

“And so what is that to me?”

“Indeed, sir, it may be naught to you,” Shakespeare replied, a touch defensively, “but the news we bring you of your son may not be naught at all.”

“Bah! Do not plague me with your riddles, you mountebank! What news have you of my son? Speak plainly and try not my patience!”

“We believe that your son is planning to elope,” said Smythe.

“Elope!” Locke gave out a barking laugh. “What nonsense! What earthly reason would he have to do such a damned fool thing?”

“Because the father of the prospective bride has now withdrawn his consent to the marriage and forbidden Thomas ever to see or speak with her again,” Smythe replied.

“And we have heard this from your son’s own lips this day.” added Shakespeare.

Locke frowned and lowered his staff. “Indeed? And did he tell you why Mayhew has done this?”

Smythe hesitated slightly, then replied, “He said ‘twas because his mother is a Jew.”

For a moment, Locke simply stood there, saying nothing. His already stormy countenance betrayed little more response. Then he finally replied. “If you are lying about this because you are bent upon some sort of mischief, then so help me Almighty God, I shall have your hearts cut out.”

Shakespeare swallowed nervously and turned a shade paler. Smythe merely returned Locke’s steely, level gaze. “Sir, I know full well just who you are, and that you are fully capable of making good upon your threat. Given that knowledge, then, consider how foolish we would have to be to play at making mischief for a man such as yourself.”

Locke’s gaze never wavered. He merely nodded once, then curtly said, “Why do you come to me with this? What concern is it of yours? Did you hope to gain some favour or ask for something in return for imparting this most unfortunate news?”

“Indeed, sir,” Shakespeare began, “the truth of the matter is that we had thought the doing of a favour for a man in your particular position could be of some considerable benefit to struggling players such as ourselves, and — ”

Smythe interrupted him before he could continue. “Nay, the truth, sir, is that ‘twas all my fault and, as such, my conscience did bid me cry to make amends.”

“Oh, Good Lord…” muttered Shakespeare, rolling his eyes. “Explain yourself,” said Locke curtly.

In as few words as possible, because he could clearly see that Locke would not have any patience for long-winded explanations, Smythe described how it happened that he advised Thomas to dope with Portia if he truly believed that he could not bear to live without her. Locke listened impassively. When Smythe was finished, he took a deep breath and exhaled heavily. He looked down at the ground for a moment, as if digesting everything that he had heard and considering it carefully, then he looked up once again, fixing Smythe with a very direct, unsettling gaze. The wind from the river had picked up, and as it blew the old man’s hair back, away from his face, and plucked at his dark, coarse woollen cloak, Smythe thought he looked for all the world like some biblical prophet, an angry Moses about to cast his staff down before the pharaoh.

“Methinks you are a man who does not shy from the consequences of his actions,” he said to Smythe. “I respect that. But there is one thing that you have not yet told me, and that is why you saw fit to offer your opinion on this matter to my son, who was essentially a stranger to you.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Merchant of Vengeance»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Merchant of Vengeance» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Merchant of Vengeance» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.