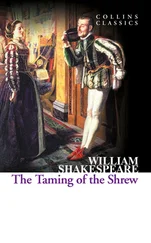

Simon Hawke - The Slaying Of The Shrew

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Simon Hawke - The Slaying Of The Shrew» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Slaying Of The Shrew

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Slaying Of The Shrew: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Slaying Of The Shrew»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Slaying Of The Shrew — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Slaying Of The Shrew», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Bestill yourself, you clever quillmaster,” Elizabeth said, sharply. “ ‘Twas not you that I was asking!”

“Mum’s the word, ma’am. I shall take my cue from womankind and be all ears.”

“And I shall box those ears for you if you do not have a care!”

Smythe laughed.

“Laugh all you like,” Elizabeth said, “but when you are done, I shall still be waiting for my answer. I am not distracted.”

“Well… she said…” Smythe shrugged with exasperation. “In all truth, Elizabeth, I cannot recall now what she said, only that what she said seemed very bold. If I had not known better, I might have thought that she had set her cap at me.”

“Blanche has set her cap at men so many times that it has grown quite threadbare,” Elizabeth replied, dryly.

“A woman’s wit is never quite so sharp as when it pricks another woman,” Shakespeare said.

“Provoke me more and you shall find that it can prick a poet, too! Besides, I speak naught but the truth. And there are others, I am sure, who can bear witness to it. Her flaws are plain for all but men to see, who see them not for being blinded by her beauty.”

“And yet ‘twas Catherine who had the worse reputation of the two,” said Smythe.

“Aye, for being a shrew,” Elizabeth replied. “For that is what men call a woman who dares to speak her mind. But if she should speak with other parts of her anatomy, then men will think with other parts of theirs, as well.”

“Which part would that be, pray tell?” Shakespeare asked, in-nocentiy.

“In your case, I have no doubt ‘twould be the smallest.”

Smythe laughed. “ Twould seem she can box a poet’s ears!”

“ ‘Twere not my ears that she defamed,” Shakespeare replied, with a grimace. And then his expression softened. “Why, Elizabeth, you are crying.”

“ Tis for Catherine,” she replied, her voice quavering. “Oh, I do not know how I can stand it! My heart is breaking!”

“There now,” Shakespeare said. “No shame in tears for a departed friend.”

He offered her his handkerchief. Unfortunately, the kindly intention of the gesture was overwhelmed by the sheer filthiness of the grimey handkerchief, which he had earlier used to wipe away some of the mud with which his face was still besmirched. Elizabeth simply stared at the muddy rag for a moment, then started to laugh, despite herself. Smythe and Shakespeare both joined in, and she put her arms around their waists as they staggered together around the house, toward the other side, helpless with laughter.

“Thank you,” Elizabeth said, as the wave of laughter subsided. “Thank you both for being such good friends.”

“Well, in truth, Elizabeth,” Shakespeare replied, “I fear I cannot claim that I was always a good friend to you.”

“How so? And why not?”

“I must admit that upon more than one occasion, I had told Tuck here that you would only bring him trouble.”

“And so I have,” Elizabeth replied.

“Do not say that, Elizabeth,” Smythe protested.

“ Tis naught but the truth, Tuck,” she replied, with a sigh. “From the day we first met at the theatre, I have only brought you trouble. And Will, too. I cannot forget that he was nearly killed on my account.”

“ Tis true that I was very nearly killed,” said Shakespeare, “but ‘twas not on your account, Elizabeth.”

“I know,” she said, “but neither you nor Tuck would ever have found yourselves placed in harm’s way had you not chosen to befriend and aid me. And now it has happened once again. You might have been killed or badly injured in that wreck, and twice now Tuck was nearly killed. And all on my account!”

“Well… when you put it that way, it does seem as if all the fault is yours,” said Shakespeare.

“Will! For God’s sake, she feels badly enough as things stand!”

“I spoke in jest,” Shakespeare replied. “So far as I can see, Elizabeth, if you were at fault in anything, ‘twas in going along with Catherine in this hare-brained scheme, but then you were only trying to help a friend and I cannot fault you in that. I would do no less for Tuck, nor Tuck for me. That misfortune has befallen is in some part, doubtless, due to Fate, but in part due also to the intervention of others. ‘Tis there the true blame lies, and ‘tis there that we must seek to place it.”

“I agree,” said Tuck, emphatically. “We know that two of the guests here are impostors, and that those two are likely to be found among Blanche’s suitors. Some we have already managed to eliminate from our consideration, but that still leaves Braithwaite, Camden, Holland, and Dubois, and their respective ‘fathers,’ if fathers they truly be.”

“Aye,” said Shakespeare. “And I am somewhat disposed towards eliminating Braithwaite from our list of suspects, too.” “Why?” asked Smythe.

“Well… he seems a very decent sort of fellow,” Shakespeare said. “And I have a good feeling about him.”

“I see. So you wish to eliminate him from consideration merely because you happen to like him?”

“Not entirely. He is the one suspect who does not have a father present, and we are looking for two men. Although I do admit I like him. He is a very likeable young man.”

“That very quality makes for a good cozener,” said Smythe.

“What, are you suggesting that I could be easily taken by some sharp cozener?”

“Will, anyone could be taken by a cozener, especially a sharp one,” Smythe replied. “Do you think you are immune because, as a poet, you are a great observer of human nature and its foibles? Well, with all due respect, by comparison, you are but an apprentice at the art of observation. A good cozener is a master of observing human nature and its foibles. If I have learned nothing else since I have arrived in London, I have at the very least learned that!”

“I suppose you have a point,” said Shakespeare, “although my instincts still tell me that he is no more and no less than what he represents himself to be. What do you know of him, Elizabeth?”

“No more than you,” she replied. “He seems like a nice young man, and he has good manners. ‘Twould seem that he has breeding. Beyond that, I can tell you nothing more. I have not had much to do with him.”

“Well, what of Dubois?” asked Smythe. “You seemed to have had rather more to do with him,” he added, and immediately regretted it. Still, he could not prevent himself from going on. “You seemed quite taken with him when I saw the two of you out walking.”

Elizabeth smiled. “Monsieur Dubois is very charming. His manners are exquiste and his sense of fashion is impeccable. He is capable of learned discourse on such things as poetry and history and philosophy. I cannot imagine that he could be some sort of criminal.”

“I find it even more difficult to imagine that he could be searching for a wife,” said Smythe.

“The ladies here all seem to find him very handsome,” said Elizabeth.

“And how do you suppose he finds the ladies? Or does he even bother looking?”

“Such pettiness does not become you,” said Elizabeth. “You could do well to emulate Monsieur Dubois.”

“I do not think I could quite manage the walk,” said Smythe, dryly.

“Oh, but I should like to see you try,” said Shakespeare.

“I think that you are both being very rude,” Elizabeth said. “Phillipe Dubois is a gentleman in every sense of the word.”

“Well, be that as it may,” said Smythe, “I think we can probably agree that Dubois is not a very likely suspect. Still, one never knows. I should like to see what Sir William makes of him, but regretably, he has not returned. What about Camden?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Slaying Of The Shrew»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Slaying Of The Shrew» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Slaying Of The Shrew» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.