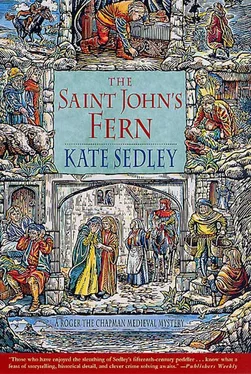

Kate Sedley - The Saint John's fern

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kate Sedley - The Saint John's fern» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Saint John's fern

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Saint John's fern: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Saint John's fern»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Saint John's fern — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Saint John's fern», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘A rumour or two has reached us,’ said the carter, nodding, ‘even in Tavistock, where I live, but that was some time ago. What’s the upshot?’

‘At the moment, there is none. It seems the Duke has neither been released nor yet brought to trial, and what will be the outcome no one can say for certain. The King’s forgiven his brother so often in the past that the general opinion is that he’ll do so again. But for the time being, at least, while Clarence is imprisoned, we’re spared the threat of further civil war.’

My new acquaintance grimaced. ‘As bad as that, was it? We heard that the Duke had been making mischief again, but not how serious it was. Well, well! But I don’t suppose it’ll affect us much down here, whatever happens.’ And the conversation drifted towards more trivial matters: the bad state of the roads the unseasonable warmth of the weather, the rapidity with which the nights were already drawing in.

As we approached Plympton Priory, my companion suddenly asked, ‘Do you have anywhere to stay in Plymouth?’ And at the first shake of my head he added, ‘I’ll give you my daughter’s direction, in Bilbury Street.’

‘That — that’s very kind of you,’ I stammered. ‘But as I said just now, I haven’t really decided-’

‘Better still,’ he interrupted, ‘if you care to wait for me while I deliver this load of peat to the priory, I’ll take you on to Plymouth myself. My wife was saying only last night that neither of us has seen Joanna for quite some time, nor our son-in-law and the grandchildren, and that one of us — meaning me, of course — ought to make the effort to find out how they’re faring. So here’s my chance. I’ve no more deliveries today and if you’ll be so good as to give me your company, it’ll make the journey that much less tedious, and you’ll be fixed up with a comfortable billet into the bargain. What do you say?’

What could I say in the face of so much kindness and goodwill? God was forcing my hand and there was nothing I could do about it unless I wished to appear worse than churlish. Suppressing a sigh, I gave in with as much good grace as I could muster and thanked him with a spurious heartiness.

‘If you’re certain it’s not too much trouble-’ I added, but my companion cut me short.

‘No trouble in the world. That’s settled then.’ He spoke with undisguised satisfaction.

Plympton Priory is an Augustinian foundation, and I was interested to note that the canons wore little black birettas on the crowns of their heads, which, upon enquiry, I was informed was because they were untonsured. Their cassocks were mainly woven from a very fine wool, and the whole place exuded wealth and luxury. I was reminded of something that I had either read or been told a long time ago, probably during my years at Glastonbury, to the effect that the Augustinian Black Canons were always well-shod, well-fed and well-clothed; that they went abroad in the world, mixed with whom they liked and talked at table. I recalled my youthful envy of an order whose rules were so far removed from those of the Benedictines, and my dissatisfaction with the life that my mother had chosen for me had increased.

‘Well, let’s be on our way,’ said the carter, whose name I had by now learnt was Peter Threadgold, climbing up on the box seat of the empty cart and indicating to me that I should do the same.

We had been given a dinner of soup and bread and cheese in the priory kitchen, during which time, by the greatest good fortune, the squally shower that I had earlier noted on the horizon, had passed over Plympton and was now moving further inland, towards the heart of the moor. The spears of stinging rain had given place once more to a hazy, autumnal sunshine that made every leaf, every blade of grass sparkle with a myriad rainbow drops of moisture. The track was rutted and green with weeds, revived by their sudden drink, and the smell of the river running broad and deep on our left, was, for a furlong or two, all-pervasive. But then the salt tang of the sea assaulted my nostrils and other scents were lost as I experienced yet again the old, familiar prickle of excitement.

I’m not a good sailor and I’m far happier with my feet planted firmly on shore, so I don’t know why I respond in the way that I do to the smell of the sea. But I’ve noticed throughout my life that I’m not the only confirmed landsman to do so. I can only suppose that it’s because here, in this island, and in neighbouring Ireland, whichever way you travel, the sea is at the end of so many journeys, and has a meaning, a significance, even for those people who have never seen it. The mere thought of it quickens the blood, and the sight of it sends a thrill of anticipation coursing up and down the spine. I think all islanders must have a little salt in their veins, for I noticed that Peter Threadgold also raised his head and sniffed appreciatively as we passed through the Old Town Gate.

‘Here we are then,’ he said, as we traversed the main street of Old Town Ward before turning left into Bilbury Street, where his daughter lived.

This, as both the name of the gate and ward made obvious, was the oldest part of Plymouth, many of the houses and cottages in Bilbury Street having been built, so Master Threadgold somewhat apologetically informed me, well over a hundred years earlier. I had to admit, although not aloud, that most of them looked it, quite a few being almost derelict and others hovering on the brink of decay. One or two, however, were well maintained, the outside walls being washed with that mixture of potash and sulphur which turns them a delicate greenish-grey, and holes in the thatch having been patched with iris leaves, a plant which grew in abundance in some of the gardens.

To my relief, it was in front of one of these better-kept cottages that we finally drew up, having driven almost the entire length of the street.

‘Whoa, boy!’ my companion exclaimed, pulling on the reins, although the cob’s pace was so steady that the order was superfluous, the lightest of touches being sufficient to stop him in his tracks.

Immediately ahead of us was another of the town gates — Martyn’s Gate, Peter Threadgold said — which, as I was to learn later, gave access to the east-bound road that passed the Carmelite Friary just beyond the walls. The cottage before which we had halted was separated from the gatehouse by only one other dwelling, a two-storeyed edifice in excellent repair, its wooden frontage painted red and gold, and with a tiled roof from which no slates appeared to be missing. It was far superior to any other building in the street, money having obviously been lavished upon its upkeep, and no expense spared to ensure that it was at once recognizable as the residence of a gentleman. There was something not quite right about it, however, but it took a moment or two for me to realize just what it was. Then it dawned on me that every window in the house was shuttered in spite of the warmth and brightness of a sunny afternoon, and that the door was not only inhospitably shut, but the knocker had been removed, leaving merely the iron hook from which the clapper had been suspended.

Peter Threadgold, whose eyes had followed my gaze, remarked, ‘That’s strange! Master Capstick must have gone away, although at his age, I shouldn’t have thought-’

He was interrupted by the emergence from the cottage of two very excited small boys, one about five, the other, I judged, a couple of years younger, and, hard on their heels, a woman whose plump, smooth face was wreathed in smiles.

‘Grandda! Grandda!’ The children reached up their little arms, trying ineffectually to drag their grandsire from his seat, while their mother laughingly admonished them.

‘Robin! Thomas! That will do! Behave! Father, what a lovely surprise. Come down before the boys do you a mischief.’ She caught sight of me. ‘And … and your friend, also,’ she added uncertainly.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Saint John's fern»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Saint John's fern» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Saint John's fern» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.