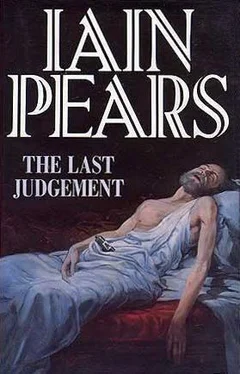

Iain Pears - The Last Judgement

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iain Pears - The Last Judgement» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Victor Gollancz, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Last Judgement

- Автор:

- Издательство:Victor Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0575055841

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Judgement: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Last Judgement»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Last Judgement — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Last Judgement», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Besides, this was the bit of his trade that he liked. Dealing with recalcitrant clients, and bargaining and extracting money and working out whether things could be sold at a profit were the bread and butter of his life, but he didn’t really enjoy them much. Too much reality for him to cope with comfortably. A meditative hour in a library was far more to his taste.

The question was where to start. Muller said he’d read about it, but where? He was half minded to ring the man up, but reckoned he’d have gone to work, and he didn’t know where that was. Anyway, a skilled researcher like himself could probably find out fairly quickly anyway.

All he knew about the picture was that it was by a man called Floret; and he knew that because it was signed, indistinctly but legibly, in the bottom left-hand corner. He could guess it was done in the 1780s, and it was obviously French.

So he proceeded methodically and with order, a bit like Fabriano only more quietly. Starting at the beginning with the great bible of all art historians, Thieme und Becker . All twenty-five volumes in German, unfortunately, but he could make out enough to be directed to the next stage.

Floret, Jean. Künstler, gest. 1792 . That was the stuff. A list of paintings, all in museums. Six lines in all, pretty much the basic minimum. Not a painter to be taken seriously. But the reference did direct him to an article published in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1937 which was his next port of call. This was by a man called Jules Hartung, little more than a biographical sketch, really, but it fleshed out the details. Born 1765, worked in France, guillotined for not being quite revolutionary enough in 1792. Served him right, as well, according to the text. Floret had worked for a patron, the Comte de Mirepoix, producing a series of subjects on legal themes. Then, come the Revolution, he had denounced his benefactor and supervised the confiscation of the man’s goods and the ruin of his family. A common enough sort of story, perhaps.

But 1937 was a long time ago, and in any case the article didn’t say where any of his pictures were, apart from hinting strongly that, fairly obviously, they no longer belonged to the Mirepoix family. For their current whereabouts he had to work a lot harder. For the rest of the morning and well into his normal lunch-hour, he trawled through histories of French art, histories of neoclassicism, guides to museums and check-lists of locations in the hunt for the slightest hint that would point him in the right direction.

He was beginning to get on the nerves of the librarians who brought him the books when at last he struck lucky. The vital information was in an exhibition catalogue of only the previous year. It had just arrived in the library, so he counted himself fortunate. A jolly little show, put on in one of those outlying suburbs of Paris trying to establish a cultural identity for themselves. Myths and Mistresses , it was called, an excuse for a jumble of miscellaneous pictures linked by date and not much more. A bit of classical, a bit of religion, lots of portraits and semi-naked eighteenth-century bimbos pretending to be wood-nymphs. All with a somewhat overwrought introduction about fantasy and play in the idealized dream-world of French court society. Could have done better himself.

However flabby the conception, however, the organizer was greatly beloved of Argyll, if only for catalogue entry no. 127. ‘Floret, Jean,’ it began rather hopefully. ‘ The Death of Socrates , painted circa 1787. Part of a series of four paintings of matching religious and classical scenes on the theme of judgement. The judgements of Socrates and of Jesus represented two cases where the judicial system had not given of its best; and the judgements of Alexander and of Solomon where those in authority had acquitted themselves a little more honorably. Private collection.’ Then a lot of blurb explaining the story behind the painting illustrated. Alas, it was not encouraging to Argyll’s hopes of finding a buyer wanting to reunite the paintings. The two versions of justice performed were out of reach, with The Judgement of Solomon in New York and The Judgement of Alexander in a museum in Germany. What was worse, The Judgement of Jesus had vanished years ago and was presumed lost. Old Socrates was liable to stay on his own, dammit.

And this catalogue didn’t even say who it used to belong to. No name, no address. Just ‘private collection.’ Not that it really mattered. He felt a little discouraged, and it was time for lunch anyway. What was more, he had to get to the shops before they shut for the afternoon. It was his turn. Flavia was particular about that sort of thing.

It stood to reason, he thought as he lumbered up the stairs an hour later, bearing plastic bags full of water, wine, pasta, meat and fruit, that this previous owner lived in France. Perhaps he should at least check? He could then construct a provenance to go with the work, and that always increases the value a little. Besides, Muller had said the work had once been in a distinguished collection. Nothing like a famous name as a previous owner to appeal to the snobbism that lurks inside so many collectors. ‘Well, it used to be in the collection of the Duc d’Orléans, you know.’ Works wonders, that sort of thing. And how better to go about tracking him down than to contact Delorme? Courtesy demanded that he should fill the man in about Muller’s decision, and pleasure indicated the need to tell him that, because of Argyll’s diligent labours in the library, he could well make more money on reselling the picture than Delorme did on flogging it in the first place.

Unfortunately, his telephone call to Paris went unanswered. Perhaps, one day, when the European Community has finished deciding on the right length for leeks, and standardizing the shape of eggs and banning everything that is half-way pleasant to eat, it might turn its attention to telephone calls. Every country, it seems, has a different system, so that all of them together make up a veritable songbook of different chirrups. A long beep in France means it is ringing; in Greece it means it’s engaged and in England it means there is no such number. Two chirrups in England means it’s ringing; in Germany it means engaged and in France, as Argyll discovered after a long and painful conversation with the telephone operator, it means that moron Delorme had forgotten to pay his phone bill again and the company had taken punitive action.

‘What do you mean?’ he said. ‘How can it have been disconnected?’

Where do they get them from? There is something about telephone operators — one of the universal constants of human existence. From Algeria to Zimbabwe, they are capable of imbuing an ostensibly polite sentence with the deepest of contempt. It is impossible to talk to one without finally feeling chastened, humiliated and frustrated.

‘You disconnect the line,’ she said, in answer to his question. Everybody knows that, she left unsaid. It’s your fault for having doubtful friends who don’t pay their bills — that passed by equally silently. She even refrained from saying that the chances were that Argyll’s line would probably be disconnected any day now as well, a shifty character like him.

Could she find out when it was disconnected? Sorry. What about if there was another line for the same name? No. Change of address? ’Fraid not.

Half enraged, half perplexed, Argyll hung up. Good God, he might have to write a letter. Years since he’d done anything like that. Rather lost the habit, in fact. Quite apart from the fact that his written French was a bit dodgy.

And so he flicked through his phone book to see who else he knew in Paris who might be persuaded to do him a favour. No one. Damn it, he thought as the phone rang again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Last Judgement»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Last Judgement» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Last Judgement» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.