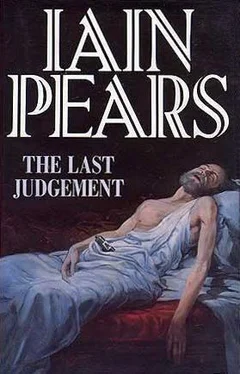

Iain Pears - The Last Judgement

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iain Pears - The Last Judgement» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Victor Gollancz, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Last Judgement

- Автор:

- Издательство:Victor Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0575055841

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Judgement: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Last Judgement»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Last Judgement — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Last Judgement», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

With enormous difficulty, she pulled the glove over the hand again. Even when the scarred, brown claw with its two remaining misshapen fingers had vanished underneath its covering, Flavia could still see it, and still felt sick. Nothing could bring her to offer any assistance.

‘But I survived, after a fashion. I was still in Paris at the Liberation. They couldn’t be bothered to send me east, and didn’t have time to shoot me before the troops arrived. As quickly as possible, I was shipped to England. To the hospital, the asylum, and finally here. Then you come; to remind me, and tell me it’s not all over yet.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Flavia said in a whisper.

‘I know. You needed information, and I’ve told you what I know. Now you must repay me by helping Jean.’

‘What happened afterwards? To your husband?’

She shrugged. ‘He got let off lightly. He came back to France after the war, expecting that nobody would know what had happened. But Jean and I had survived. I didn’t know what to do, but I knew I couldn’t see him. Jean was behind the push to get him brought to justice. Not for revenge, but for the sake of the people who’d died. Despite everything, he felt it was like condemning his own father. The commission wrote to me; very reluctantly, I agreed to give evidence.

‘Fortunately it wasn’t necessary. When he was confronted with the facts and the promise of our testimony, Jules killed himself. Simple as that.’

‘And Arthur?’

‘He was better off where he was. He thought I was dead, and he had a good family to look after him. Better he didn’t know. I wrote to his foster-parents, and they agreed to keep him. What could I do for him? I couldn’t even look after myself. He needed to start afresh, without any memories from the past, of either his father or mother. I asked them to make sure he knew nothing of either of us. They agreed.’

‘Rouxel?’

She shook her head. ‘I didn’t want to see him. His memory of what I was like was all I had left. I couldn’t bear to have him come into my hospital room and see his face change into one of sympathetic horror the way yours did. I know. There’s nothing you could do. It’s an involuntary reaction. People can’t help it. I loved him, and he loved me; I didn’t want that destroyed by his seeing me. No love could survive that.’

‘Did he not want to see you?’

‘He respected my wishes,’ she said simply.

Something unsaid there, Flavia thought. ‘But surely...’

‘He was married,’ she said. ‘Not to a woman he loved, not someone like me. But he married when he thought I was dead. After the war he discovered the truth; he wrote to me, saying that if he’d been free... But he wasn’t. It was better like that. So I accepted Harry’s offer as well.’

‘Do you know anything about Hartung’s paintings?’ Argyll asked, changing the subject somewhat dramatically.

She looked puzzled. ‘Why?’

‘All this started off with a picture which belonged to him. Called The Death of Socrates . Did your husband give it to Rouxel?’

‘Oh, that. I remember that. Yes, he did. Just after the armistice. He decided that the Germans would probably take them anyway, so he gave some pictures away to friends for safe-keeping. Jean got that, to go with one he’d already been given. A religious one, that was. Jean was quite perplexed and didn’t really want it, I think.’

‘Did Hartung know about you and Rouxel?’

She shook her head once more. ‘No. Never a murmur. I owed him that. Within his limits he was a good husband. Within mine I was a good wife. I never wanted to hurt him. He never had the slightest idea. And I was always careful with Jean as well. He was a hot-blooded, passionate man. I was terrified he might go to Jules and tell him, hoping he’d divorce.’

She’d begun to cry again, at all the memories and the lost joys of life. Flavia had to decide whether to stay and offer comfort or just leave. She wanted to know more. What did she mean, she’d been careful with Rouxel? But she seemed to have had enough, and any comfort offered was not going to do much good. Flavia stood up, and turned to face the bed. ‘Mrs Richards. I can only thank you for your time. I know we’ve made you remember things you want to forget. Please forgive us.’

‘I will forgive you. But only if you fulfil your side of the bargain. Help Jean, if he needs it. And when you do, tell him that it was my last gift of love to him. Will you do that? You promise?’

Flavia promised.

Going back out into the cool fresh air and feeling the soft warmth of the sun was like waking up after a nightmare and finding that the horrors were not real after all. Neither of them said anything as they walked to the car, got in, and Argyll started the engine and drove off.

A mile down the road, Flavia grabbed his arm and said: ‘Stop the car. Quickly.’

He did as she asked, and she got out. There was a break in a hedge near by, and she walked through it into a pasture. On the far side there were some cows grazing.

Argyll caught up, to find her staring across the field at nothing, breathing heavily.

‘You OK?’

‘Yes. I’m OK. I just wanted some air. I felt I was suffocating in there. God, that was horrible.’

There was no need either to comment or even to agree with her. Side by side they walked slowly around the field in silence.

‘You’re thoughtful,’ he said eventually. ‘Something beginning to make sense?’

‘Yes,’ she replied. ‘Not there yet, but it’s coming. I wish it wasn’t.’

‘Come on,’ he said softly after a while. ‘Let’s get going. You’ll feel better once we start doing something.’

She nodded and he led her back, then drove to the hotel where he steered her into the bar, ordered a whisky and made her drink it.

In all, it took her nearly an hour plunged in thought before she was able to lift her head and say, ‘What do you think?’

And Argyll wasn’t concentrating on anything, either. ‘I think it’s the first time I’ve ever met anyone where I could honestly say she’d be better off dead. But I suppose that’s not what you meant.’

‘I didn’t mean anything. I just wanted to hear someone talk normally. Anything. Even you seem to have lost your flippant style.’

‘All I know is that we now have another good reason for working this mess out. It’s not going to make much difference to her life, but someone owes her a little. Even if it’s just guarding her memories.’

17

Very tired and downcast, Argyll eased Edward Byrnes’s unscratched Bentley into a parking-space outside the art dealer’s house at about half-past seven, then they went and rang the doorbell.

‘Flavia!’ came a booming voice from the direction of the sitting-room as the door opened. ‘About time, too.’

Following the voice after a second or so came the body of General Bottando.

‘My dear girl,’ he said solicitously. ‘I’m so pleased to see you again.’

And, with a most unprofessional lapse into emotionalism, he wrapped his arms around her and gave her a squeeze.

‘What are you doing here?’ she said in astonishment.

‘All in due course. First, you look as though you need a drink.’

‘A big one,’ Argyll added. ‘And some food.’

‘And then you can tell us what you’ve been up to. Sir Edward here delivered your message, and I thought it was time I got on a plane to have a chat. You seem remarkably unwilling to come back home,’ Bottando said as he led the way into Byrnes’s sitting-room.

‘How about you telling me what you’ve been doing?’ asked Flavia, following him in.

Bottando said calmly, ‘Do you want some of Sir Edward’s gin?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Last Judgement»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Last Judgement» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Last Judgement» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.