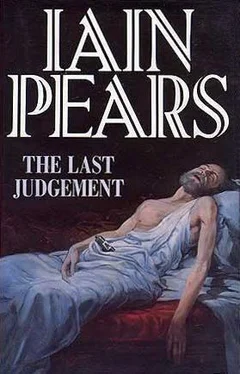

Iain Pears - The Last Judgement

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iain Pears - The Last Judgement» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Victor Gollancz, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Last Judgement

- Автор:

- Издательство:Victor Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0575055841

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Judgement: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Last Judgement»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Last Judgement — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Last Judgement», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Just something I was told.’

‘Oh, no, miss. Maybe you’ve got the wrong person. No, he were a doctor. A surgeon. A what-d’-you-call-it. The ones that put people back together.’

They searched their respective vocabularies for the right word.

‘A plastic surgeon?’ she suggested after various other strands of the profession had been eliminated from their enquiries.

‘That’s the one. He started working on burn victims in the war. You know, soldiers. People like that.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Oh, yes. I remember that very well.’

‘So how old was he?’

‘When he died? Oh, ever so old, he was. A bachelor, most of his life. Everyone was so surprised when he married her. Pleased, of course; but surprised as well.’

Flavia’s conversation with the barman put both of them off their meal which, considering the price, was something of a waste.

‘But we can’t have made that much of a mistake, surely?’ Argyll asked as he pushed his food around the plate with a fork. ‘Was this man certain there were no children?’

‘Absolutely. Once he finally opened up, he seemed to know the life-histories of everybody within thirty miles of here. He was very definite. Richards was a pioneering plastic surgeon. He set up a specialized burns unit in Wales during the war and worked there straight through. He was also in his late forties then. He only married once, and to this woman after the war. No children.’

‘Not, in other words, the sort of person to be found working with the Resistance in Paris in 1943.’

‘No.’

‘Which leaves cousins, nephews, brothers and things like that.’

‘I suppose so. But the barman didn’t mention any.’

‘Look on the bright side,’ he said as cheerily as possible. ‘If he was the one we were after, then he’d be dead and that would be that. As he probably wasn’t, there’s still a faint chance we might get somewhere.’

‘Do you really think that?’ she asked sceptically.

He shrugged. ‘Might as well, for want of anything better to think. Where is this Manor Farm place? Did you find out?’

She had. It was about two miles to the west of the village. She had the directions. Argyll suggested they go out there. There was nothing else to do, after all.

16

Before they set out, they did their best to ring in advance to give warning of their arrival. But, as the barman pointed out, it was not so easy as Mrs Richards had no telephone. She had a permanent nurse and an odd-job man who kept the house running. Apart from those two, she saw and talked to virtually no one. He was not convinced she was going to welcome their visit. But if they were friends of her husband’s — he made no attempt to disguise the fact that he found this a little unlikely — she might agree to see them.

Having little alternative, they piled in their car and drove the two miles or so to Turville Manor Farm. It was a much grander establishment than Flavia had expected from the narrow gap in the hedge and the muddy, neglected track that led away from the small road to the house. Nor was it a farm, as far as she could tell; at least, there was no sign of anything remotely agricultural.

However attractive it might have been — Argyll, who knew about this sort of thing, guessed the builders had been at work on it round about the time that Jean Floret was putting the finishing touches to his painting of Socrates — the handsomely proportioned house was not looking its best. Somebody, at some time, had begun painting a few of the dozen windows in the main façade, but had apparently given up after three of them; on the rest the paint was peeling, the wood was rotting and several panes of glass were broken. A creeper had gone wildly out of control along one side of the building. Rather than adorning the house, it showed signs of taking over entirely; another couple of windows had vanished completely under the foliage. The lawn in front was a complete wreck, with weeds and wild flowers spreading luxuriantly over what had once been a gravel driveway. If they hadn’t been told the place was inhabited, both of them would have assumed it was abandoned.

‘Not the do-it-yourself type,’ Argyll observed. ‘Nice house, though.’

‘Personally I find it thoroughly depressing,’ Flavia said as she got out and slammed the door. ‘It’s confirming my already strong feeling that this is a waste of time.’

Privately Argyll agreed, but felt it would be too discouraging to say so. Instead he stood, hands in pockets, a frown on his face, and examined the building.

‘There’s no sign of life at all,’ he said. ‘Come on. Let’s get this over with.’

And he led the way up the crumbling, moss-covered steps to the main door and rang the bell. Then, realizing it didn’t work, he knocked, first gently, then more firmly, on the door.

Nothing. ‘Now what?’ he asked, turning to look at her.

Flavia stepped forward, thumped the door far more aggressively than he had and, when there was again no response, turned the handle.

‘I’m not going all the way back just because someone can’t be bothered to answer,’ she said grimly as she went in.

Then, standing in the hallway, she shouted, ‘Hello? Anybody home?’ and waited while the faint echo died away.

Many years ago it had been an attractively furnished house. No wonderful hidden treasures, certainly, but good solid furniture entirely in keeping with the architecture. Even a good dust and clean would work wonders, Argyll thought as he turned and looked around him. But at the moment the atmosphere of gloom and dereliction was overpowering.

It was also cold. Even though it was about as warm outside as an English autumn could ever get, the house had an air of dampness and decay that only long neglect can produce.

‘I’m starting to hope there isn’t anyone here,’ he said. ‘Then we can get out of this place fast.’

‘Shh,’ she replied. ‘I think I can hear something.’

‘Pity,’ he said.

There was a scraping noise coming from up the dark and heavily carved staircase; now that he stopped and listened, Argyll knew she was right. It was not at all clear what it was, though; certainly not a person walking.

They looked at each other uncertainly for a moment. ‘Hello?’ Argyll said again.

‘There’s no point in standing down there shouting,’ came a thin, querulous voice from the landing. ‘I can’t come down. Come up here if you have any serious business.’

It was not just an old voice, but also a sick one. Quiet but not gentle, unattractive and even unpleasant in tone, as though the speaker could barely be bothered to open her mouth. Odd accent as well.

Argyll and Flavia looked at each other uncertainly. Then she gestured for him to go ahead and he led the way up the stairs. The woman stood half-way along a dimly lit corridor. She was clad in a thick, dark green dressing-gown and her hair hung in long, thin strands around her face. Her legs were encased in thick socks, her hands in woollen mittens. She was clutching on to a tubular steel walking-frame, and it was this, painfully inching its way along the wooden floor, which made the noise they’d heard.

The old woman herself — they assumed this must be the reclusive Mrs Richards — was breathing hard, making a rasping noise as she sucked the air in, as though the effort of walking what appeared to have been only about fifteen feet was more than she could manage.

‘Mrs Richards?’ Flavia gently asked the apparition, elbowing her way past Argyll as they approached.

The woman turned and cocked her head as Flavia approached. Then she narrowed her eyes slightly and nodded.

‘My name is Flavia di Stefano. I’m a member of the Rome police force. From Italy. I’m most dreadfully sorry to disturb you, but I wondered if we could ask you some questions.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Last Judgement»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Last Judgement» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Last Judgement» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.