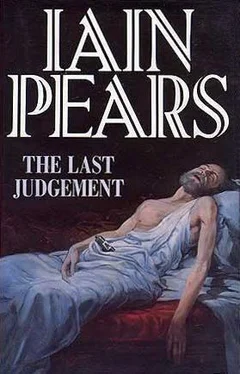

Iain Pears - The Last Judgement

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iain Pears - The Last Judgement» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Victor Gollancz, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Last Judgement

- Автор:

- Издательство:Victor Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0575055841

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Judgement: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Last Judgement»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Last Judgement — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Last Judgement», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Guynemer nodded understandingly and, very irritatingly, launched into a monologue about the pictures and what he knew about them, mentioning, among other things, the article in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts and a host of other references which Argyll, for the sake of appearances, duly wrote down.

‘So,’ the Frenchman said when he finished, ‘could you tell me, Mr Argyll, why it is that you say you have never heard of the Gazette article when you’ve read my exhibition catalogue which refers to it several times? And how it is that you say you are in the fourth year of writing a book on neoclassicism and still know next to nothing about the subject?’

Damnation, Argyll thought. Must have said something wrong again.

‘Just stupid, I guess,’ he said abjectly, trying to look like a particularly slow student.

‘I don’t think so,’ said Guynemer with a brief smile, almost as if he felt apologetic for bringing up such a tasteless topic of conversation. ‘Why don’t you just tell me why you are really here? Nobody likes to be made a fool of, you know,’ he added a little reproachfully.

Oh, dear. Argyll hated the reasonable ones. Not that the man didn’t have good reason to feel a little annoyed. Telling lies is one thing; telling bad ones is quite another.

‘OK,’ he said. ‘Full story?’

‘If you please.’

‘Very well. I’m not a researcher, I’m a dealer and at the moment I am providing a little practical assistance to the Italian art police. At the moment I have in my possession a painting by Floret entitled The Death of Socrates . This may have been stolen, no one seems sure. The buyer was certainly tortured to death soon after I brought it to Rome; another man interested in it was also murdered. What I need to know is where the picture came from, and whether it was stolen.’

‘Why don’t you ask the police in France?’

‘I have. That is, the Italians have. They don’t know.’

Guynemer looked sceptical.

‘It’s true. They don’t. It’s a long story, but as far as I can see they are as mystified as anyone else.’

‘So you come to me.’

‘That’s right. You organized this exhibition with the picture in it. If you won’t help, I don’t know how else to go about it.’

Appeal to the human side. Look pathetic and pleading, he thought. Guynemer considered the matter awhile, clearly wondering which was the least likely, Argyll’s first story or his second. Neither, in truth, was exactly straightforward.

‘I’ll tell you what,’ he said eventually. ‘I can’t give you the name. It’s confidential, after all, and you don’t exactly inspire confidence. But,’ he went on as Argyll’s face fell, ‘I can ring the owner. If he is willing, then I can put you together. I shall have to go and find out the details. I didn’t actually do that section of the exhibition myself. That was Besson’s part.’

‘What?’ said Argyll. ‘Did you say Besson?’

‘That’s right. Do you know him?’

‘His name wasn’t in the catalogue, was it?’

‘Yes. In small print at the back. A long story, but he left the project half-way through. Why do you ask?’

It seemed time to be open and honest about things; weaving tangled webs had got him nowhere, after all. But it might well turn out that Besson and Guynemer were bosom buddies and he would be thrown out on his ear in a matter of minutes if he were straightforward. In which case it would be a case of so near and yet...

‘Before I say, can I ask why he left?’

‘We decided that he was not suitable,’ Guynemer parried back. ‘A clash of personalities. Your turn.’

‘This picture, if it was stolen, subsequently turned up in Besson’s hands. I don’t know yet how it got there.’

‘Probably because he stole it,’ Guynemer said simply. ‘He’s that sort of person. That’s why he wasn’t suitable. When we found out. We hired him as an expert in tracking paintings down and getting their owners to lend them. Then we discovered that we were in effect helping to introduce a wolf into a sheep pen, so to speak. The police got wind of it and came to warn us. Once I saw the dossier on him—’

‘Ah.’

‘So, if I may take it one stage further for you, he would have known where this picture was, and may well have visited the house where it was kept. Draw any conclusions from that you want.’

‘Right. Did you not like him?’

The subject of Besson did nothing for Guynemer’s amiability. Clearly he had a lot to say, but decided against saying it. However, he indicated that they were not close.

‘But I think I should go and find out about your picture, do you not?’

And he disappeared for about five minutes, leaving Argyll to stew silently.

‘You’re in luck,’ he said when he returned.

‘It was stolen?’

‘That I couldn’t tell you. But I spoke to the owner’s assistant, and she is prepared to meet you to discuss the matter.’

‘Why couldn’t this woman just say?’

‘Possibly because she doesn’t know.’

‘Is that likely?’

Guynemer shrugged. ‘No more unlikely than anything you’ve told me. Ask yourself. She will meet you at Ma Bourgogne in the Place des Vosges at eight-thirty.’

‘And now can you tell me who is the possible owner?’

‘A man called Jean Rouxel.’

‘Do you know him?’

‘ Of him. Of course. A very distinguished man. Old now, but immensely influential in his day. He’s just been awarded some prize. It was in all the papers a month or so ago.’

Research is the secret of the good dealer; this was the little motto that Argyll had adopted in the few years since he had taken up the business. It wasn’t necessarily true; at least, it was clear that he knew an awful lot about pictures he hadn’t managed to sell, while colleagues unloaded others so fast they wouldn’t have had time to find out about them even if they’d been so minded.

Clients were a different matter. However philistine some dealers may be — and many take a very jaundiced view indeed of the things they sell and the people they sell to — all believe that the more you know about a client the better. Not about the ones who wander in off the street, see something they like and buy; they don’t matter. It’s the private clients who deserve this treatment, the ones who, if you work out their tastes and inclinations properly, may come back again and again. Such people vary from the idiots who like to say loudly at dinner parties ‘My dealer tells me...’ right through to the serious, judicious collector who knows what he wants — ninety nine out of hundred collectors are men — and will buy if you provide it. The former type is lucrative, but no pleasure to deal with; a good relationship with the latter can be as enjoyable as it is profitable.

So Argyll set to work on Jean Rouxel, not in the hope, this time, of selling him anything, but merely to know what he was getting involved in. For this task he had to go to the Beaubourg, which houses the only library in Paris regularly open after six o’clock in the evening. Fortunately it was not raining; the place becomes strangely popular when it’s wet, and queues form outside the door.

Merely being in the place put him in a bad mood. Argyll liked to think of himself as a liberal sort, open to modern ideas and a fully paid-up believer in the notion that education was a good thing. The more people had it, the better the world would be. Stood to reason, although in the twentieth century the available evidence seemed to contradict the idea. Many academics he’d met didn’t help the argument, either.

Being on the fifth floor of the Pompidou Centre, however, made Argyll’s belief wobble. The building itself he loathed: all that dirty glass and peeling paintwork on pipes. Classical buildings can take grime; a bit of weathering even improves them sometimes. The high-tech look just seems battered, sad and miserable when it stops being squeaky-clean.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Last Judgement»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Last Judgement» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Last Judgement» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.