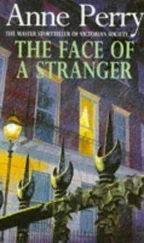

The next few moments were imprinted on Hester’s heart forever. Alastair gamed his breath and swam strongly over to Oonagh, a mere stroke or two away, and for an instant they were face-to-face in filthy water, then slowly and with great care he reached out and grasped her heavy hair and pushed her head under. He held it while she flailed and thrashed. The tide caught him and he ignored it, allowing it to take him rather than let go of his dreadful burden.

Monk looked on in paralyzed horror.

Hester let out a scream. It was the only time she could remember screaming in her life.

“God help you!” Hector said thickly.

There was no more commotion in the water. Oonagh’s hair floated pale on the surface and her skirts billowed around her. She did not move at all.

“Sweet Mary, mother of God!” the fishwife said from behind Monk, crossing herself again and again.

At last Alastair looked up, his face smeared with mud and his own hair. He was exhausted; the tide had him and he knew it.

As if woken from a dream, Monk turned to the fishwife. “Have you got a rope?” he demanded.

“Holy Virgin!” she said in horrified awe. “You’re never going to hang ‘im!”

“Of course not, you fool! I’m going to get him out!”

And with that he lashed the rope to the stanchion, the other end around his waist, and leaped into Ihe water and was immediately carried by the current away from the wall and the still-visible floating roof of the carriage.

Others had gathered around. A man in a heavy knitted sweater and sea boots took the weight of the rope, and another went to the edge with a rope ladder.

It was ten minutes before Monk was hauled back and helped in. The fishermen took the bodies from him, and lastly eased him, shivering, streaming water, onto the quayside. He clambered to his feet slowly, his clothes weighing him down.

A little bunch of people stood around, pale-faced, fascinated and flustered as they laid Oonagh on the stones, her skin marble gray, her eyes wide open, and then Alastair beside her, calmer, ice-cold and beyond her reach.

Monk looked down at her, then at Hester, instinctively as he always did, and in that moment he realized the enormity of what lay between them now. He would never seek to put from his mind the night in the secret room, even if he could, nor would he have undone it, but it created new emotions in him he did not want. It opened up vulnerabilities, left him wide open to wounds he could not cope with.

He saw in her face that she understood, that she too was uncertain and afraid; but she was also in that instant certain beyond anything and everything else that there was a trust between them older and stronger than could be broken, something that was not love, although it encompassed it and anger, and differences: true friendship.

He was afraid that she had already seen that it was the most precious thing in the world to him. He looked away quickly, down at the dead face of Oonagh. He reached out a hand and closed her eyes, not out of pity, just a sense of decency.

“The sins of the wolf have come home,” he said quietly. “Corruption, deceit, and last of all, betrayal.”