And ne’er was heard of more: but ‘tis supposed,

He lived and died among the savage men.

I have a deal more time on my hands. My hosts have continued to be accommodating and I am allowed light and space in which to write, as well as a limited number of foolscap sheets and a single pencil. No pen, unfortunately — I have often requested an inkwell and nib, but there is some petty rule here about spiked implements and sharp points. They do not discourage my work, though at the end of each day everything is taken from me for safekeeping. I feel sure that my skill has grown with the tale’s telling and I am concerned that the opening sections must seem amateurish and crude in comparison with later chapters. I have repeatedly asked if I might not be allowed the complete manuscript, if only for an hour or two, so that I might make some revisions and clarifications from which the work can only benefit. To date, they denied my every request.

No doubt you can tell from the clinical manner in which I have related this narrative that I am not a man inclined to excesses of the imagination.

However, I have been much troubled of late by a recurring dream.

It is not as other dreams — no fragmentary jumble of dredged-up memories and half-forgotten faces, no meaningless kaleidoscope of impossible juxtapositions and incongruities. Nor does its detail fade and vanish in the morning but lingers in my mind long after I have woken, acquiring such permanence and solidity that I wonder if what I have seen is not somehow more than the fantasies of sleep but a piece of reality. The truth.

Every time it is the same. It begins deep in a forest, all light beneath the canopy of trees tinted a dusky green, strange birds screeching overhead, creatures chittering unseen in the undergrowth. I see twelve people — six men, six women — trekking through the woods, often having to hack and battle their way through the foliage but, rather wonderfully, always endeavoring to walk forward in pairs, in crocodile formation, like schoolchildren on a day trip to the zoo. Some of them I recognize — Mr. Speight, Mrs. Grossmith, Mina the bearded whore. Dear Charlotte is with them, too, radiant even as she battles, perspiring, with tree-roots and recalcitrant branches, her natural beauty complemented and enhanced by that of her surroundings.

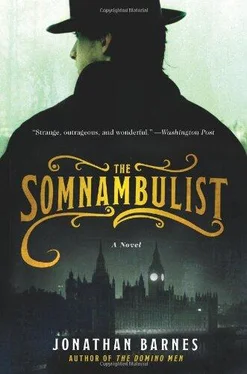

At the head of the party is a man I do not recognize at first. Completely bald, his pate gleams with sweat as he leads the others through the trees. Baffled, I watch his progress for a while until at last it comes to me. Even though I have had this dream dozens of times before, on every fresh occasion I am astonished by the realization. It is the Somnambulist, stripped at last of his sideboards and wig, of the props and make-believe of his life with Moon, come at last into the cleansing light of revelation. His skin is untanned and, as ever, he says nothing.

At length, the party emerges at the edge of the forest on a small promontory some feet from the ground. They look down and see below them the great expanse of the Susquehanna, its thick blue ribbon coiling through the landscape, framed on either side by lush, glorious swathes of perfect green, unpeopled, fertile, poised for Pantisocracy.

The Somnambulist gazes upon this sliver of Eden and smiles. Then he opens his mouth and — to my everlasting surprise and joy — he speaks. His voice sounds nothing like what I had expected.

“Well, then,” he says. “Where do we start?”