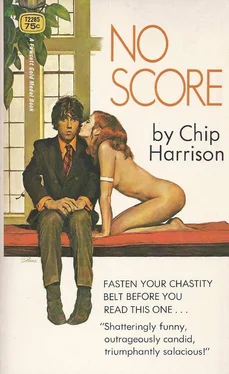

Lawrence Block - No Score

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Lawrence Block - No Score» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Greenwich, Год выпуска: 1970, ISBN: 1970, Издательство: Fawcett Publications, Жанр: Иронический детектив, Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:No Score

- Автор:

- Издательство:Fawcett Publications

- Жанр:

- Год:1970

- Город:Greenwich

- ISBN:978-0451187963

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

No Score: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «No Score»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

No Score — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «No Score», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was a fishing rod. The way I was dressed, there were only two things on earth I could be — a criminal on the run or a lunatic fisherman. So I took the fishing rod and transformed myself from a Threat To Society to an All-American Boy, and I walked right through the dippy town without a bit of trouble.

If this was a movie, the thing to do now would be to cut straight on through to September. Not for the sake of cheating, the way they do when they refuse to tell you how Stud Boring got dressed again, but just because nothing very interesting happened during the next two months. And if we just cut to two months later and fifteen hundred miles east of there, you wouldn’t miss much.

But if you’re like me you always want to know about things like that, like what happened during the two months it took me to get from the fifth largest city in Indiana to where I was in September, which is also where I am now. If I like a book and get interested, I want to know everything.

When it comes to novels, I like the old-fashioned approach where they tell you what happened to the characters after the book ended. You know, the plot’s all tied up and the story is all used up and done with, and then there’s a last chapter where the author explains that Mary and Harold got married and had three children, two boys and a girl, and Harold lived to be sixty-seven when a stroke got him, and Mary survived him by twenty years and never remarried, and George went back together with his wife but they broke up again after three years, and George went to California and has never been heard from since, and his wife died of pleurisy the year after he left. I like to feel that the people are so real that they go on doing things even when the book is done with them, and sometimes I’ll make up my own epilogue for a book in my head if the author didn’t write one himself. It’s called an epilogue when you do this.

Anyway, ever since I started writing this, in fact ever since Mr. Burger said I really ought to write it, I decided I would just act as though the person reading it was more or less like myself. With a similar way of looking at things and so on. So whenever I have to decide whether to put something in or not, I ask myself whether or not I would want to read it. That’s why I put in all that crap about the termite racket, for example.

What I did for the rest of July and all of August and the first week of September was farm work, for the most part. I headed east when I left town and didn’t stop walking and hitchhiking until I was in Ohio. I didn’t think the police would bother sending out an alarm for me, since I wasn’t exactly Public Enemy Number One. I mean I wasn’t the most sought-after criminal since Arlo Guthrie dumped the garbage in Stockbridge, Mass. I was breathing fairly easy as soon as I got out of the county, but I still thought it would be good to get across the state line without taking any chances.

I kept getting lifts for a couple of miles at a time because this particular highway wasn’t one that anybody would take for any great distance. But on a bigger road I would have stood out like acne with my clothes and my fishing rod. On this road people either assumed I was going to a particular fishing spot or when they asked I would just say Down the road a piece and they figured I was keeping the spot a secret. Fishermen do crazy things like that all the time. Then I would just sit in the car until they let me out because they were turning off.

Eventually, though, I got sick of having to talk about fishing with people who all knew more about it than I did. And I got sick of carrying the pole. So I left it on a bridge over a little creek that I happened to walk over between rides. I figured whoever found it would be able to get some use out of it right away.

Then, since I didn’t have the pole, people assumed I was a drifter, which was what I was, actually. And one man said, “Bet you’re looking to get work picking. Cherries is gone but early peaches is coming in, and won’t be a week and they be picking summer apples, the weather the way she be.”

I hadn’t even thought about it. I wasn’t in shape to think any further than the Ohio line, to tell the truth. But farm work sounded as good as anything else I could think of, and it turned out to be just right, considering the circumstances.

You didn’t need a car or a suit or a degree or any experience whatsoever. You could walk in off the road wearing paint-smeared dungarees and muddy shoes and a hunting jacket and not get looked at twice. If they had berries or melons that needed picking, or peaches or apples or sweet corn or tomatoes, they didn’t care where you went to school or who your father was or if you had a Social Security card. All they cared was if you wanted to get out in the field and pick the stuff.

Of course they didn’t pay much, either. They really couldn’t. Look, a pint of blueberries, say, will cost you maybe half a dollar at the supermarket, right? Suppose the farmer who grew it got half of that, which he never does, I don’t think, unless he sells it himself or something. But anyway, say he gets a quarter a pint. Now if you ever picked blueberries you know that it takes forever to fill a pint container with the stupid little things. You could get the whole quarter for picking those berries and it wouldn’t be exactly the highest wages in history, and that would mean the farmer was giving the berries away for nothing.

But even with the pay low, and even with being on your feet all day, and getting up early in the morning and working twelve or fourteen hours at a stretch, even with all of that, there were good things about it. Even with the backache you got from picking stuff that grew on the ground, or the bruises you got from falling off ladders while picking stuff that grows on trees, it was still a good way to cover two months and fifteen hundred miles.

For one thing, you could really eat as though food was free, because it just about was. You were expected to eat all you wanted of whatever you were picking while you picked it. (This was more of a thrill when what you were picking was red raspberries than when it happened to be summer cooking apples.) You also got three meals a day. Breakfast was three or four eggs fresh from the hen and home baked bread and jam. All the fruits and vegetables were fresh at lunch and dinner, and they kept passing huge oval bowls full of different things around the table.

I had never eaten like that in my life. Not to say anything against my mother, but she wasn’t the world’s greatest cook. I suppose when you can function as a confidence woman for twenty years without ever getting caught, you can also let other people do the cooking for you. Still, I ate better at home than I did at any of the camps or schools I went to, and from the last school I had gone more or less directly to Aileen’s instant coffee and non dairy creamer and TV dinners, moving on to third rate restaurant food in Illinois and Indiana towns. I had gotten so I never cared much about food, probably because I didn’t really know what good food tasted like. I always thought I hated vegetables, for instance, because the ones I ate always came out of cans or plastic bags and then sat on the stove for a couple of months.

Besides the food, the life was just generally healthy. They usually let you sleep in the barn, except a couple of times in large apple orchards in New York State, where there were just more pickers than there was floor space. Even then they took care of us, though, with straw mattresses to sleep on and sheets of canvas to tie to the trees and sleep under, not just because it might rain but so that apples wouldn’t drop on top of you.

What I mostly picked was apples. Supposedly you could make better money working vegetable farms, but I really hated the stooping, and I never got used to the feel of the sun on the back of my neck. An apple orchard is cool on hot days and had a great smell to it and you work standing up. Of course you have to expect to fall off the ladder once in a while. They say that anybody who doesn’t fall now and then isn’t picking fast enough. I won’t say that you get used to falling off ladders, or that you grow to look forward to it, but in all the time I picked apples, I never got more than a bruise or saw anybody do worse than sprain a wrist. You learn how to fall after the first couple of times, and it sort of struck me, during one of the moments of philosophical reflection that you get plenty of in an apple orchard, that anybody who lived the kind of life I did really ought to learn how to fall.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «No Score»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «No Score» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «No Score» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.