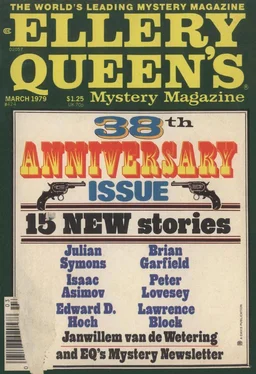

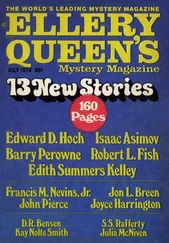

Isaac Asimov - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Isaac Asimov - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1979, ISBN: 1979, Издательство: Davis Publications, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979

- Автор:

- Издательство:Davis Publications

- Жанр:

- Год:1979

- Город:New York

- ISBN:ISSN: 0013-6328

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Prove it, you Keystone Cop, I thought grimly. I was sweating freely now, and I surreptitiously wiped my palms on my skirt.

He transferred his attention to the typewriter then, and suddenly he stiffened. He reached for a 3x5 memo pad and tore off a page, inserting it in the machine. He tapped out six letters, glanced over at me, and ripped the paper out of the roller. He picked up the plastic-wrapped yellow sheet, put the 3x5 page on top of it, and walked over to me. He handed me the papers without comment, his eyes cold, and the word he’d typed leaped out at me, turning me cold. It read:

“I don’t understand,” I said weakly.

But I did. I knew now what I’d overlooked, the damning thing that gave it all away. I stared at the ugly word that stood out black and clear against the pale typing on the yellow sheet underneath it, and I shivered.

“He wrote that paragraph, all right, Mrs. Marlin,” said Chief Holbrook. “But it was part of the story he was working on.

“A man doesn’t type out a suicide note and then put a new ribbon in his machine.”

Waiting for Mr. McGregor

by Julian Symons [19] © 1979 by Julian Symons.

Julian Symons is one of the finest writers of crime and detective stories, both long and short, in our time. So you can imagine our delight when Mr. Symons advised us that he had written a new series of four contemporary short stories. You will find the stories different in theme, background, and storyline, but alike in reflecting Mr. Symons’ approach to the modern mystery story, alike in revealing Mr. Symons’ writer’s-eye-and-mind, with characterization as important in the scheme of things as suspense and the sequence of events.

“Waiting for Mr. McGregor” will appear in an anthology titled verdict of thirteen, edited by Julian Symons, to be published by Faber & Faber in the United Kingdom and by Harper & Row in the United States.

Now, meet Hilary Engels Mannering and his BPB — his Beatrix Potter Brigade — and attend one of the strangest trials by jury on unofficial record...

Even in these egalitarian English days nannies are still to be seen in Kensington Gardens, pushing ahead of them the four-wheeled vehicles that house the children of the rich. On a windy day in April a dozen perambulators were moving slowly in the direction of the Round Pond, most of them in pairs. The nannies all wore uniforms. Their charges were visible only as well-wrapped bundles, some of them waving gloved fists into the air.

The parade was watched by more people than usual. A blond young man sat on a bench reading a newspaper. A pretty girl at the other end of the bench looked idly into vacancy. A rough-looking character pushed a broom along a path in a desultory way. The next bench held a man in black jacket, striped trousers, and bowler hat, reading the Financial Times , a man of nondescript appearance with his mouth slightly open, and a tramp-like figure who was feeding pigeons with crumbs from a paper bag. Twenty yards away another young man leaned against a lamppost.

A pram with a crest on its side approached the bench where the blond young man sat. The nanny wore a neat cap and a blue striped uniform. Her baby could be seen moving about and a wail came from it, but its face was hidden by the pram hood. The pram approached the bench where the man in the black jacket sat.

The blond young man dropped his newspaper. The group moved into action. The young man and the girl, the three people at the next bench, the man beside the lamppost, and the man pushing the broom, took from their pockets masks which they fitted over their faces. The masks were of animals. The blond young man was a rabbit, the girl a pig, the others a squirrel, a rat, another pig, a cat, and a frog.

The masks were fitted in a moment, and the animal seven converged on the pram with the crest on its side. Half a dozen people nearby stood and gaped, and so did other nannies. Were they all rehearsing a scene for a film, with cameras hidden in the bushes? In any case English reticence forbade interference, and they merely watched or turned away their heads. The nanny beside the pram uttered a well-bred muted scream and fled. The child in the pram cried lustily.

The blond young man was the first beside the pram, with the girl just after him. He pushed down the hood, pulled back the covers, and recoiled at what he saw. The roaring baby in the pram was of the right age and looked of the right sex. There was just one thing wrong. The baby was coal-black.

The young man looked at the baby disbelievingly for a moment, then shouted at the rest of them, “It’s a plant. Get away, fast!”

The words came distorted through the mask, but their sense was clear enough, and they followed accepted procedure, scattering in three directions and tearing off the masks as they went. Pick-up cars were waiting for them at different spots in the Bayswater Road, and they reached them without misadventure except for the tramp, who found himself confronted by an elderly man brandishing an umbrella.

“I saw what you were doing, sir. You were frightening that poor—”

The tramp swung a loaded cosh against the side of his head. The elderly man collapsed.

The baby went on roaring. The nanny came back to him. When he saw her he stopped roaring and began to chuckle.

Somebody blew a police whistle, much too late. The cars all got away without trouble.

“What happened?” asked the driver of the car containing the blond young man and the pretty girl.

“It was a plant,” he said angrily. “A bloody plant.”

Hilary Engels Mannering liked to say that his life had been ordered by his name. With a name like Hilary Mannering how could one fail to be deeply esthetic in nature? (How the syllables positively flowed off the tongue.) And Engels, the name insisted on by his mother because she had been reading Engels’ account of conditions among the Manchester poor a day or two before his birth — if one was named Engels, wasn’t one almost in duty bound to have revolutionary feelings?

Others attributed the pattern of Hilary’s adult life to his closeness to his mother and alienation from his father. Others said that an only child of such parents was bound to be odd. Others still talked about Charlie Ramsden.

Johnny Mannering, Hilary’s father, was a cheerful extrovert, a wine merchant who played tennis well enough to get through the preliminary round at Wimbledon more than once, had a broken nose and a broken collarbone to show for his courage at rugby, and when his rugby and tennis days were over became a scratch golfer. To say that Johnny was disappointed in his son would be an understatement. He tried to teach the boy how to hold a cricket bat, gave Hilary a tennis racquet for his tenth birthday, and patted the ball over the net to him endlessly. Endlessly and uselessly.

“What I can’t stand is that he doesn’t even try,” Johnny said to his wife Melissa. “When the ball hit him on the leg today — a tennis ball, mind you — he started sniveling. He’s what you’ve made him, a sniveling little milksop.”

Melissa took no notice of such remarks, and indeed hardly seemed to hear them. She had a kind of statuesque blank beauty which concealed a deep dissatisfaction with the comfortable life that moved between a manor house in Sussex and a large apartment in Kensington. She should have been — what should she have been? A rash romantic poet, a heroine of some lost revolution, an explorer in Africa — anything but what she was, the wife of a wealthy sporting English wine merchant. She gave to Hilary many moments of passionate affection to which he passionately responded, and days or even months of neglect.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 3. Whole No. 424, March 1979» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.