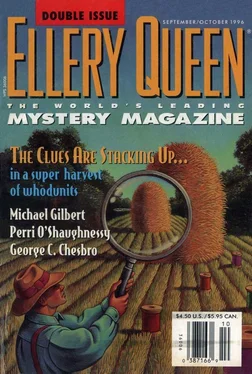

Doug Allyn - v108 n03-04_1996-09-10

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doug Allyn - v108 n03-04_1996-09-10» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Dell Magazines, Год выпуска: 1996, Издательство: Dell Magazines, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:v108 n03-04_1996-09-10

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Magazines

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- Город:Dell Magazines

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

v108 n03-04_1996-09-10: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

v108 n03-04_1996-09-10 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You — I don’t know — seem so remote,” Catherine had said to her. “The doctor says it’s simple depression—”

Simple depression? She almost laughed and had to turn her head away. She feigned a cough.

She awoke with a start in the night and lay listening for the familiar creak of the house in the wind. But there was nothing. She listened for the sounds her daughter might make while sleeping, but it was as if she had gone deaf. For a moment she debated getting up to see if Catherine was still there, but was suddenly afraid that if she tried, she might be unable to move her limbs. She sat up then, heart pounding. Then, fearing she might wake her daughter, she made herself lie back and calm herself and wait for sleep. She found herself thinking of an incident some years after her marriage to Hal.

They had been sitting one Sunday afternoon in the living room, she on the couch beneath the large window which looked out on Flagstaff and he in the leather chair which had the good light. She had looked up at him appraisingly from her puzzle, at his handsome, patrician profile. He was frowning at the journal in his hand and making notes in the margin to take some luckless scholar to task.

“What does ‘iconography’ mean?” she asked.

He stirred uneasily, as he always did when she asked him a question to which he should know the answer. She supposed that was part of the problem between them: The longer they were together, the more severe the erosion of her confidence in his omniscience as she found the soft places in his armor. By then she was experienced in doing so.

“It isn’t in this dictionary,” she said, tapping the paperback which rested against her thigh as snugly as a cat.

“An icon is—”

“I know what an icon is,” she said.

He paused, pretending that she had not interrupted him, tactfully ignoring her rudeness.

“Iconography is not, however, the study of icons, as one might guess, but rather the relationship of a group of symbols representing — or rather — bearing the meaning of a stylized work of art.”

She wondered if he was ashamed of the “or rather.” He had to know that she would recognize it as a clearing of the throat (which he knew she hated), a pause to allow him to think of a more exact reply.

“Such as? Could we perhaps provide an example?”

“If you like. Hamlet, for one. Ophelia and Polonius, Hamlet and Gertrude. The Oedipal interpretation. If one views the characters as symbols, they can be manipulated and interpreted virtually at will. A feminist version of the play — which blissfully I have neither seen nor read — purports to have Ophelia running off to join a lesbian guerrilla group. Dear God.”

He laid aside his journal and looked at her expectantly, seemingly surer of himself, as if he supposed that he had gained a foothold on the slippery slope of her esteem. She knew he wanted more.

“Does that make it clearer?” he asked. “Shakespeare is rife with examples. Take Othello —”

But she was unwilling to grant him more.

“Never mind. I get the drift.”

She was acutely aware of his disappointment. It was as if she had wantonly turned her back just as he had seized on the heart of the matter. She knew he longed for another chance to preen himself before her, but she bent her head ungenerously again to her puzzle. After a moment, she heard him pick up his magazine.

She made herself unclench her hands and spread her fingers on the cool sheets, imagining herself in the limitless landscape of the Arctic, with the wind curling the snow about her feet like smoke.

She had been twenty-four years old when she had gone back to school and taken her first course from Hal. Catherine was five. Sarah was newly divorced and embarrassed at being such an old undergraduate. When asked, she would say that she was “going for her doctorate,” for she had every intention of doing so. That was the price her husband had been willing to pay for an uncontested divorce. He would support her and the child until she had collected whatever degrees she could. It was more than generous, but then the divorce had not been her doing. She had left the university after her sophomore year to marry Catherine’s father in haste, and as it had turned out, unwisely.

After the divorce, she had found a woman to look after the child during the day and had returned to school eagerly. On the first day of her Milton class she had thought Hal the most attractive man she had ever seen. He was elegantly slender and impeccably dressed in a blue blazer, snowy oxford-cloth shirt with a button-down collar, tailored tan slacks, and a blue and red and white striped tie. His cordovan loafers were so highly polished she was sure he could see his reflection there as he appeared to study them for prompts, rather than the notes stacked neatly on the lectern. While gathering his thoughts, he seemed to prefer to fix on such lowly objects: an imaginary crumb on his spotless tie, a piece of lint on his sleeve. Sometimes he formulated his answer to the rare question in the glowing tip of the omnipresent cigarette, omnipresent despite the prominent NO SMOKING sign posted at the upper right-hand corner of the blackboard. Later she would find that he glanced at the sign at the start of each class before bending his sleek head to light his cigarette. She decided he did so to avoid embarrassing students who might otherwise have pointed it out to him, by making it obvious that he knew it was there. But it also had the effect of impressing on them that ordinary rules applied only to ordinary people. They did not apply to him.

He was a Milton man, the youngest tenured professor on campus and already chairman of Graduate Studies in English. Even so, he was fifteen years her senior.

She went to him during his posted office hours with a difficulty with her term paper on Comus. They went for coffee.

He was not divorced but was separated from his wife who lived in the East. Their affair was discretion itself until Hal had obtained his divorce. Most of his colleagues were stunned when they married. Though they showed her pitiless courtesy, they treated her much the way Hal himself had treated her almost from the beginning, as though she were an attractive, precocious child whose opinions were to be tolerated, not valued.

She stopped her formal schooling after she got her B.A. Though her grades were excellent, going on for an advanced degree would have been too awkward as long as Hal was chairman of Graduate Studies. Besides, she had a young girl to rear.

“What are you going to do?” her daughter asked her over breakfast. “You’re still a young woman.”

She had not been unprepared for the question but thought its timing inappropriate. Did one bury one’s husband one day and go to work for IBM the next? She decided her daughter was old enough to know better and would not profit from a rebuke.

“I suppose I’ll go back to the zoo,” she said cautiously.

“In Denver?” Her daughter frowned.

“Boulder doesn’t have one.”

“Yes, I mean, but that’s awfully far away to drive, isn’t it? Even if it is only a couple of days a week. Can’t they get along without you for a while?”

Perversely, her daughter now seemed to feel resuming her activity of choice was a desecration of her weeds.

“It’s only two mornings,” Sarah said.

“But they don’t even pay you for it,” Catherine said.

“I don’t need to get paid for it. I enjoy it. It pleases me.”

Her daughter nodded, humoring her, no doubt.

“And I intend to travel,” Sarah continued. “There is a trip I want to take to Canada before Thanksgiving. Travel is one antidote to ‘simple depression,’ don’t you think?”

“Of course it is,” her daughter said. “But it’s an odd time of year to go to Canada, if you don’t mind my saying so.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.