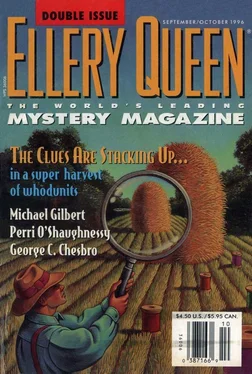

Doug Allyn - v108 n03-04_1996-09-10

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doug Allyn - v108 n03-04_1996-09-10» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Dell Magazines, Год выпуска: 1996, Издательство: Dell Magazines, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:v108 n03-04_1996-09-10

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Magazines

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- Город:Dell Magazines

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

v108 n03-04_1996-09-10: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

v108 n03-04_1996-09-10 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I nosed around the office, prowled like a caged lion, glancing out of the window. The front window looked out onto the street. Sitting at his desk, where he was shot in the head, Rabbi Weissman could have easily been targeted by the hypothetical neo-Nazi in a car. It had been a warm night, the windows were open—

No one could have come through the back window. A small stream ran muddily under the window. Anyone shooting through that window would have had to slosh through the murky water and would have alerted the rabbi to his presence. But the rabbi had been found slumped over his desk, facing away from the back window, facing the front. That would be well and good except that the shot was to his left temple. Anyone shooting from the street couldn’t have hit his temple unless—

Unless it wasn’t someone shooting from the street.

I shook my head. The old dictum of childhood rose, rumbled, warned. “Never suspect another Jew.” It would be easy, too easy, to drown the appointment book, to look no further, to gloss the whole thing over and the hell with MacAllister.

But no, there was also a commitment to the truth, to justice. (And more phrases from childhood rose, unbidden: “God’s first word is Truth and His Justice is eternal.”) Slowly, reluctantly, I opened the desk drawers. And, sure enough, the appointment book was where the young man had said it would be: in the top right-hand desk drawer. Feeling like an intruder, as I always did when going through the personal effects of someone else — living or dead — I opened it to the date of his death.

Appointments: Mrs. Faige Cohen, 9:00, Mr. David Brown, 9:30, Mr. and Mrs. Hyman Nahmanson, 10:00.

A new round of interviews, as I trudged from door to door.

Faige Cohen, a diminutive, white-haired, shriveled-up old lady, had come to see the rabbi regarding a confusion of pots and pans. She had cooked a chicken in her dairy pan, and had her grandchildren coming tomorrow. Was the chicken kosher, since dairy could not be mixed with meat? Could she serve the chicken? Her voice shook as she recounted the rabbi’s remarks. “I–I was so upset, you know, since my husband Joseph died, may he rest in peace, I don’t have much money, just my little pension, and I didn’t know how I would replace a whole chicken. And the rabbi, may he rest in peace, said I should just go ahead and use the chicken.” No, she knew no one who could wish him ill, she was home by 9:25, and the bus driver on the number 155 line could identify her if necessary.

David Brown was a young man, barely out of his teens, a yarmulke resting unevenly on a shock of red hair. “It was a weird situation I went to see the rabbi about. A religious question, you know, and I was sure the rabbi would say no, no way.” He shook his head and folded his arms. “But he said yes.”

“Yes to what?”

“Well, I’m in college, you know. And, like, most professors usually don’t schedule exams on Saturdays because of Shabbos, the Sabbath. They’re usually pretty considerate of the Orthodox students, and they know our rules. See, we don’t write on Sabbath, you know.”

I nodded. I knew.

“Well, I couldn’t get microeconomics rescheduled. A bitch of a professor, she’s real nasty and I’m sure she’s anti-Semitic. You know. And she had to go and schedule our big final right on Saturday. I couldn’t get out of it, I would’ve failed, you know, and, like, I didn’t know what to do. But Rabbi Weissman threw me for a loop. He said yes, I should go take the exam, I could write if I needed to.”

To write on Saturday? This was bizarre. To violate Sabbath? The chicken was possible, even though my own training told me that a chicken cooked in dairy utensils was treif, unkosher, and had to be discarded. But maybe the rabbi, with his learning and his expertise, knew of some loophole, some leniency that I wasn’t aware of. But Sabbath was inviolable, except in life-threatening situations. Something was odd, incongruous. It was with a strange, queasy feeling (not dissimilar to the squishing in my stomach the first time I ate pork) that I proceeded to the Nahmansons.

The door was opened by a thin, bearded, bespectacled young man, obviously in the middle of dinner — (he was still holding his fork, and a napkin was tucked in his pants). A petite, kerchiefed woman peeked out shyly from the kitchen.

Greetings, apologies about the interrupted dinner, then on to business. “Why did you come to see Rabbi Weissman the night of his death?”

A jump, the couple was obviously startled. A glance passed between them, frightened, tremulous. “How did you know? This was a — a very private matter, nobody was supposed to know we came.”

“And nobody did.” I tried to make my voice as soothing as possible. “Your names were in his diary, that’s how I found out.”

The news didn’t seem to relieve them. “I’m sorry,” said Hyman. “But it’s too private to talk about.”

“In a murder investigation, I’m afraid nothing can be kept private.”

Again the flutter, the frightened glances. “Please believe me when I say that nothing we talked to the rabbi about could have possibly been connected with this horrible tragedy. It was — it was a highly personal matter.”

God, how I hated this part of it. The pushing, the prying. “I’m sorry, really I am, but a man is dead, and these are questions I have to ask.”

The petite woman burst into tears and ran out of the room.

Hyman glared. “Well, if you must know—” He thrust out his lip belligerently. “We’re newlyweds. Married three months ago. Rabbi Weissman performed the ceremony.” He paused, licked his lips, his beard trembling. “I — we — I mean, my wife — are you familiar with the Orthodox marriage laws?” Before I could nod, he plunged on. “A man can’t touch his wife — make love, even hand her a plate — during her menstrual period, and for seven days afterward. My wife has had something which Jewish law sees as a long period. She just won’t stop staining. The doctor says that’s normal during times of stress and transition. But it’s been hell.” His voice broke, he covered his face. “A tease, a miserable tease, to share a room with your new bride, a woman you can’t even touch. Your wife. We couldn’t stand it anymore, we went to Rabbi Weissman hoping there was some leniency he could find. And he studied the holy books and — well, he found a way.” A tiny smile creased the tormented face. “Even when she’s staining, we can still hug, hold hands, and—” his face reddened and he looked at the floor “—well, you know.”

I knew. I knew. I knew the torment, I knew the liberation, and I knew so much more.

I knew before I reentered the study, before I opened the holy books that were strewn across the desk, that the rabbi had consulted (or pretended to consult). I knew before I unearthed my rusty Hebrew, cleaned it and oiled it and used it to delve into those ancient tomes. There was no way, not within Jewish law, that Hyman could be allowed to touch his wife while she was staining. Not during her period. It was a cardinal sin, a violation of all the tenets and codes, tantamount to eating on Yom Kippur, and worse, far worse, than eating pork, worse than violating the Sabbath, the penalty for which is death.

The rabbi was cutting corners. No, that was an understatement. Rabbi Weissman had completely dumped Jewish law — at least any law that made life inconvenient, difficult, or painful for its followers.

And, sitting in his chair, I thought I understood. “You do not understand a man until you’ve stood in his shoes,” so say the rabbis. Sitting in Rabbi Weissman’s chair was enough.

The stream, the endless stream of sorrows and pleas, the burden of being spokesman for a God of dread and restriction, of rules and penalties, when inside, it was all crumbling, the demon of doubt growing, consuming him, chasing him from pulpit to lectern to podium to sing the praises of the faith in flawless Hebrew and propound its mystery and its wonder. To sing to himself, to that part of himself that held the memory of swastikas and babies’ blood, still raw, still screaming from within the void.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «v108 n03-04_1996-09-10» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.