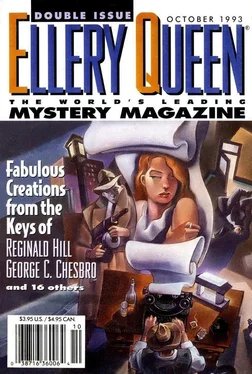

Charles Ardai - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Charles Ardai - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1993, Издательство: Davis Publications, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993

- Автор:

- Издательство:Davis Publications

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In the last summer before schooltime, 1909, everyone heard the cry of “John, John, the dog-faced one,” and even I, his friend, saw him newly. I would look at him with a blank face, until he would notice this, and then he would say crossly, with one of his impulsive, self-clutching movements,

“What’s the matter, Richard, what’s the matter, why are you looking crazy?”

“I’m not looking crazy. You’re the one that’s crazy.”

For children pointed at him and sang, “Crazy, lazy, John’s a daisy,” and ran away.

Under their abuse, and my increasing wonderment, John showed a kind of daft good manners which should have induced pity and grace in his tormentors, but did not. He would pretend to be intensely preoccupied by delights and secrets from which the rest of us were excluded. He would count his fingers, nodding at the wrong total, and then put his thumbs against his thick lips and buzz against them with his furry voice, and look up at the sky, smacking his tongue, while other boys hooted and danced at him.

They were pitiably accurate when they called him the dog-faced one. He did look more like a dog than a boy. His pale hair was shaggy and could not be combed. His forehead was low, with a bony scowl that could not be changed. His nose was blunt, with its nostrils showing frontward. Hardly contained by his thick, shapeless lips, his teeth were long, white, and jumbled together. Of stocky build, he seemed always to be wearing a clever made-up costume to put on a monkey or a dog, instead of clothes like anybody else’s. His parents bought him the best things to wear, but in a few minutes they were either tom or rubbed with dirt or scattered about somewhere.

“The poor dears,” I heard my mother murmur over the Burley family.

“Yes,” said my father, not thinking I might hear beyond what they were saying, “we are lucky. I can imagine no greater cross to bear.”

“How do you suppose—” began my mother, but suddenly feeling my intent stare, he interrupted, with a glance my way, saying,

“Nobody ever knows how these cases happen. Watching them grow must be the hardest part.”

What he meant was that it was sorrowful to see an abnormal child grow physically older but no older mentally.

But Mr. and Mrs. Burley — Gail and Howard, as my parents called them — refused to admit to anyone else that their son John was in any way different from other boys. As the summer was spent, and the time to start school for the first time came around, their problem grew deeply troubling. Their friends wished they could help with advice, mostly in terms of advising that John be spared the ordeal of entering the rigid convention of a school where he would immediately be seen by all as a changeling, like some poor swineherd in a fairy story who once may have been a prince, but who would never be released from his spell.

The school — a private school run by an order of Catholic ladies founded in France — stood a few blocks from our street. The principal, who like each of her sisters wore a white shirtwaist with a high collar and starched cuffs and a long dark blue skirt, requested particularly that new pupils should come the first day without their parents. Everyone would be well-looked-after. The pupils would be put to tasks which would drive diffidence and homesickness out the window. My mother said to me as she made me lift my chin so that she could tie my Windsor tie properly over the stiff slopes of my Buster Brown collar, while I looked into her deep, clear, blue eyes, and wondered how to say that I would not go to school that day or any other,

“Richard, John’s mother thinks it would be so nice if you and he walked to school together.”

“I don’t want to.”

I did not mean that I did not want to walk with John, I meant that I did not want to go to school.

“That’s not very kind. He’s your friend.”

“I know it.”

“I have told his mother you would go with him.”

Childhood was a prison whose bars were decisions made by others. Numbed into submission, I took my mother’s goodbye kiss staring at nothing, eaten within by fears of the unknown which awaited us all that day.

“Now skip,” said my mother, winking both her eyes rapidly, to disguise the start of tears at losing me to another stage of life. She wore a small gold fleur-de-lis pin on her breast from which depended a tiny enameled watch. I gazed at this and nodded solemnly, but did not move. With wonderful executive tact she felt that I was about to make a fatally rebellious declaration, and so she touched the watch, turning its face around, and said, as though I must be concerned only with promptness.

“Yes, yes, Richard, you are right, we must think of the time, you mustn’t be late your first day.”

I was propelled then to the Burleys’ house next door, where John and his mother were waiting for me in their front hall, which was always filled with magic light from the cut-glass panes in bright colors flanking their front door.

Mrs. Burley held me by the shoulders for a moment, trying to tell me something without saying it.

“Richard,” she said, and then paused.

She looked deep into my eyes until I dropped my gaze. I looked at the rest of her face, and then at her bosom, wondering what was down there in that shadow where two rounded places of flesh rolled frankly together. Something about her personality led people to use her full name when they referred to her even idly — “Gail Burley” — and even I felt power within her.

Her husband had nothing like her strength. He was a small grey man with thin hair combed flat across his almost bald skull. The way his pince-nez pulled at the skin between his eyes gave him a look of permanent headache. Always hurried and impatient, he seemed to have no notice for children like me, or his own son, and all I ever heard about him was that he “gave Gail Burley anything she asked for” and “worked his fingers to the bone” doing so, as president of a marine engine company with a factory on the lake-front of our city of Dorchester in upstate New York.

Gail Burley — and I cannot say how much of her attitude arose from her sense of disaster in the kind of child she had borne — seemed to exist in a state of general exasperation. A reddish blond, with skin so pale that it glowed like pearl, she was referred to as a great beauty. Across the bridge of her nose and about her eyelids and just under her eyes there were scatterings of little gold freckles which oddly yet powerfully reinforced her air of being irked by everything.

She often exhaled slowly and with compression, and said “Gosh,” a slang word which was just coming in her circle, which she pronounced “Garsh.” Depending on her mood, she could make it into the expression of ultimate disgust or mild amusement. The white skin under her eyes went whiter when she was cross or angry, and then a dry hot light came into her hazel eyes. She seemed a large woman to me, but I don’t suppose she was — merely slow, challenging, and annoyed in the way she moved, with a flowing governed grace that was like a comment on all that was intolerable. At any moment she would exhale in audible distaste for the circumstances of her world. Compressing her lips, which she never rouged, she would ray her pale glance upward, across, aside, to express her search for the smallest mitigation, the simplest endurable fact or object of life. The result of these airs and tones of her habit was that in those rare moments when she was pleased, her expression of happiness came through like one of pain.

“Richard,” she said, holding me by the shoulders and looking into my face to discover what her son John was about to confront in the world of small schoolchildren.

“Yes, Mrs. Burley.”

She looked at John, who was waiting to go.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 102, No. 4 & 5. Whole No. 618 & 619, October 1993» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.