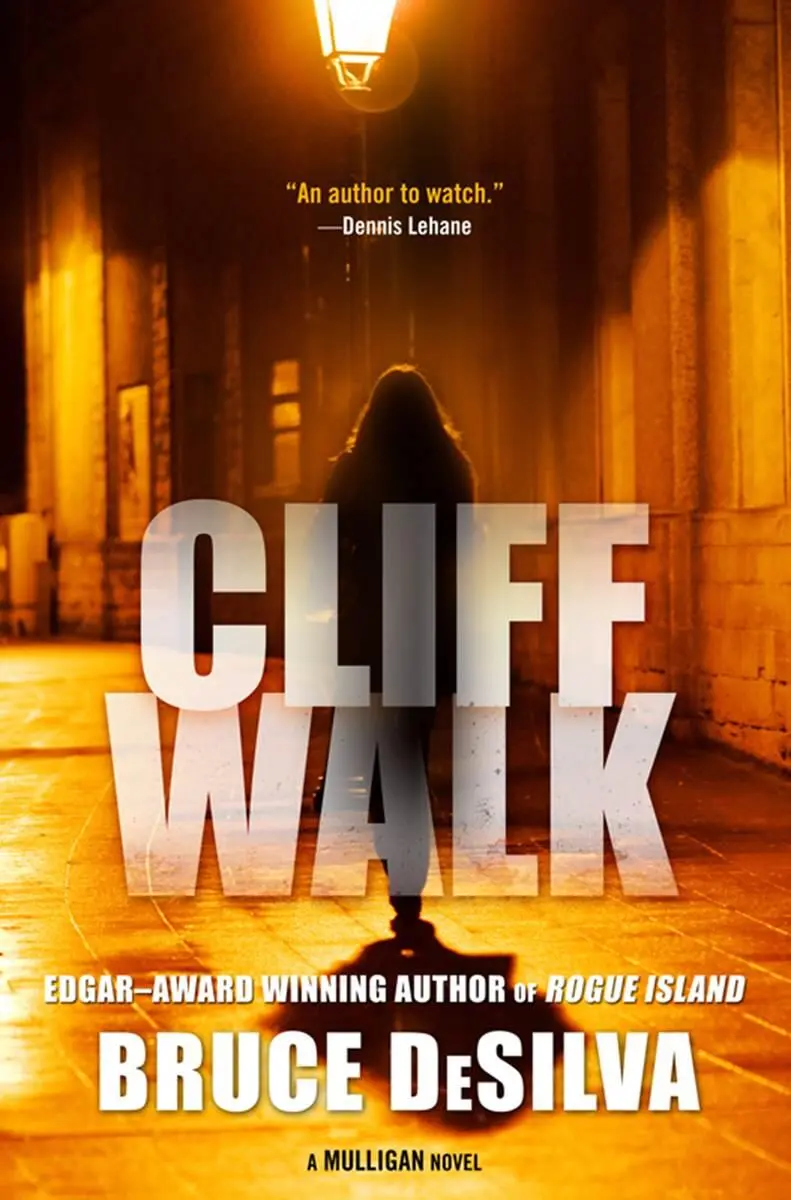

The second book in the Liam Mulligan series, 2012

For Patricia.

My lone regret is that I didn’t find you sooner.

This is a work of fiction. Although some of the characters are named after old friends, they bear no resemblance to them. For example, the real Stephen Parisi is a Providence contractor, not a Rhode Island State Police captain. A handful of real people are mentioned; but only one of them-the poet Patricia Smith-has a speaking part, and she is permitted only a few words of dialogue. I also borrowed the colorful nickname of a former Rhode Island attorney general, but the fictional and real Attila the Nun are nothing alike and the character’s actions and dialogue are entirely imaginary. References to Rhode Island history and geography are as accurate as I can make them, but I have played around a bit with time and space. For example, both the Newport Jumping Derby and Hopes, the newspaper bar where I drank decades ago when I reported the news for the Providence Journal, are long gone, but I enjoyed resurrecting them for this story. Legal prostitution, a major plot element in this book, was in fact part of life in Rhode Island until 2010; but my depiction of how and why it was finally outlawed is entirely made-up.

Cosmo Scalici hollered over the grunts and squeals of three thousand hogs rooting in his muddy outdoor pens. “Right here’s where I found it, poking outta this pile of garbage. Gave me the creeps, the way the fingers curled like it wanted me to come closer.”

“What did you do?” I hollered back.

“Jumped the fence and tried to snatch it, but one of the sows beat me to it.”

“Couldn’t get it away from her?”

“You shittin’ me? Ever try to wrestle lunch from a six-hundred-pound hog? I whacked her on the snout with a shovel my guys use to muck the pens. She didn’t even blink.”

To mask the stink, we puffed on cigars, his a Royal Jamaica, mine a Cohiba.

“Jesus, Mary, and Joseph,” he said. “The nails were painted pink, and it was so small. The little girl that arm came from couldn’ta been more than nine years old. The sow just wolfed it down. You could hear the bones crunch in her teeth.”

“Where’s the hog now, Cosmo?”

“State cops shot her in the head, loaded her in a van, and took off. Said they was gonna open her stomach, see what’s left of the evidence. I told ’em, that’s two hundred and fifty bucks’ worth of chops and bacon wholesale, so you damn well better send me a check ’less you want me to sue your ass.”

“Any other body parts turn up?”

“The cops spent a couple hours raking through the garbage. Didn’t find nothin’. If there was any more, it’s all pig shit by now.”

We kept smoking as we slopped across his twelve acres to the sprawling white farmhouse with green shutters where I’d left my car. Once this was woodland and meadow, typical of the countryside in the little town of Pascoag in Rhode Island’s sleepy northwest corner. But Cosmo had bulldozed his whole place into an ugly mess of stumps, mud, and stones.

“How do you suppose the arm got here?” I asked.

“The staties kept asking the same question, like I’m supposed to fuckin’ know.”

He scowled as I scrawled the quote in my reporter’s notebook.

“Look, Mulligan,” he said. “My company? Scalici Recycling? It’s a three-mil-a-year operation. My twelve trucks collect garbage from schools, jails, and restaurants all over Rhode Island. That arm coulda been tossed in a Dumpster anywhere between Woonsocket and Westerly.”

I knew it was true. Scalici Recycling was a fancy name for a company that picked up garbage so pigs could reprocess it into bacon, but there was big money in it. I’d written about the operation five years ago when the Mafia tried to muscle in. Cosmo drilled one hired thug through the temple with a bolt gun used to slaughter livestock and put another in a coma with his ham-size fists. He called it trash removal. The cops called it self-defense.

I’d parked my heap beside his new Ford pickup. Mine had a New England Patriots decal on the rear window. His had a bumper sticker that said: “If You Don’t Like Manure, Move to the City.”

“Getting along any better with the folks around here?” I asked as I jerked open my car door.

“Nah. They’re still whining about the smell. Still complaining about the noise from the garbage trucks. That guy over there?” he said, pointing at a raised ranch across the road. “He’s a real asshole. That one down there? Total jerk. This whole area’s zoned agricultural. They build their houses out here and want to pretend they’re in fuckin’ Newport? Fuck them and the minivans they rode in on.”

A prowl car slipped behind me on America’s Cup Avenue, and when I swung onto Thames Street, it hugged my bumper. A left turn onto Prospect Hill didn’t shake it, so when I reached the red octagonal sign at the corner of Bellevue Avenue, I broke with local custom and came to a complete stop. Then I turned right, and the red flashers lit me up.

I rolled down the window and watched in the side mirror as a Newport city cop unfolded himself from the cruiser and swaggered toward me, the heels of his boots clicking on the pavement, his leather gun belt creaking. I shoved the paperwork at him before he asked for it. He snatched it without a word, walked back to the cruiser, and ran my license and registration. I listened in on my police scanner and was relieved to learn that my Rhode Island driver’s license was valid and that the heap I’d been driving for years had not been reported stolen.

I heard the gun belt creak again, and the cop, whose name tag identified him as Officer Phelps, was back, handing my paperwork through the window.

“May I ask what business you have in this neighborhood tonight, Mr. Mulligan?”

“No.”

Ordinarily, I don’t pick fights with lawmen packing high-powered sidearms. Anyone who’d covered cops and robbers as long as I had could recognize the.357 SIG Sauer on Officer Phelps’s hip. But he’d had no legitimate reason to pull me over.

“Have you been drinking tonight, sir?”

“Not yet.”

“May I have permission to search your vehicle?”

“Hell, no.”

Officer Phelps dropped his right hand to the butt of his pistol and gave me a hard look.

“Please step out of the car, sir.”

I did, affording him the opportunity to admire how fine I looked in a black Ralph Lauren tuxedo. He hesitated a moment, wondering if I might actually be somebody; but tuxedos can be rented, and a somebody would have had better wheels. I put my palms against the side of the car and assumed the position. He patted me down, sighing when he failed to turn up a crack pipe, lock picks, or a gravity knife.

When he was done, he wrote me up for running the sign I’d stopped at and admonished me to drive carefully. I was lucky he didn’t shoot me. In this part of Newport, driving a car worth less than eighty thousand dollars was a capital offense.

I fired the ignition and rolled past the marble-and-terra-cotta dreams of nineteenth-century robber barons: The Breakers, Marble House, Rosecliff, Kingscote, The Elms, Hunter House, Beechwood, Ochre Court, Chepstow, Chateau-sur-Mer. And my favorite, Clarendon Court, where Claus von Bülow either did or did not try to murder his heiress wife by injecting her with insulin, depending on whether you believe the first jury or the second. Here, sculpted cherubs frolic in formal gardens. Greek gods cling to gilded cornices and peer across the Atlantic Ocean. Massive oak doors open at a touch, and vast dining rooms rise to frescoed ceilings. A few of these shrines to hubris and bad taste have been turned into museums, but the rest remain among the most exclusive addresses in the world, just as they have been for more than a hundred years.

Читать дальше