To make sure I’m fit to take on these children, I’ll go around the house and take every bottle and tip it down the sink. I’ll never buy alcohol again. I’ll go to AA. I’ll be a perfect father to them. Even if Lucas doesn’t want to stay with us, he’ll always be welcome here to see his sister Grace.

Today is not the day to say this to the children. Nor will tomorrow be, and perhaps not even next week, but it’s the offer I want to make them as and when they’re ready to hear it.

If Tessa will agree.

I’m willing to bargain.

If she’ll agree to this, I’ll not ask questions about how she knew, off by heart, the personal mobile phone number of Zoe’s solicitor. I’ll not phone her friends to ask if she stayed with them last night, because I think I know where she was. I think she was with him. It was her that told me, her defensiveness when I phoned him. I’m not one hundred per cent sure, I have no idea how it might have happened, but I can live with a little uncertainty. It’s a lesser demon than the ones I’ve been cohabiting with for the last few years. Tess’s infidelity is probably as much as I deserved, and it’s certainly no worse a thing than what I’ve put her through.

This is what I want to say to the children, this is what makes me feel invigorated, strong, hopeful: Stay with us. We’ll look after you. We’ll make sure no more harm comes to you. We can be your family.

From inside the house, our landline rings and I feel Tess tense up beside me.

‘I’ll get that,’ I say.

I try Tess’s landline because I feel I have to. I don’t want her to feel abandoned.

It rings and rings, and I’m about to give up when Richard answers.

I’m tempted to hang up, but that would be childish, and this is not a day for infantile behaviour.

‘Hello,’ I say. ‘It’s Sam Locke, Zoe’s solicitor, returning your call.’

I say that because I suspect he doesn’t know that Tess and I have spoken since he left his message.

He says, ‘Thank you, Sam, but we don’t need you any longer, the police have made an arrest.’

‘Yes, I saw that on the news. I’m so sorry. Is everybody all right? It must have been a terrible shock.’

‘It is a great shock, yes.’

He draws out his words as if there’s something else he’s thinking of saying and I’m suddenly alert to the fact that he might know about Tess and I.

‘Well, I won’t keep bothering you any longer, but if there’s anything I can do please just phone me.’

‘I think you’ve done enough, don’t you?’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Don’t contact my family again. Don’t contact Zoe and, most importantly, don’t contact my wife.’

‘What?’

‘I think you understand me very well.’

‘I…’

‘Leave us alone.’

‘Sorry, I…’ But my words fall into the ether because he’s hung up.

I sit with my phone in my hand and wonder if Tessa has told him about us, if she had to tell him. I’m still sitting there many minutes later, speculating, and shocked at the ferocity of his tone, when my phone rings.

Tess , I think at first, but it’s not. It’s my parents, and I can’t ignore them. Not today. My mother cries when I tell her that my diagnosis is one step nearer to being confirmed.

‘How will you manage, love?’ she asks. ‘Will you move back home?’

‘I don’t know, Mum, we’ll have to see.’

I’ve had no intention of doing that, but after I hang up I drink another beer and watch the river some more and feel the beginnings of what feels like mourning for Tessa, and then I’m tempted by my mother’s suggestion. I’m tempted to walk away from this city and this life and this relationship that’s brought me the greatest feelings of joy but also the most profound feelings of guilt. I’m tempted to nurse my sorrows elsewhere, to rethink my life.

If I take myself back to Devon where I’ll still be in pain, and my condition will inevitably degenerate, and I’ll miss Tess every day, there will at least be sea air, and beautiful countryside and people who know me and love me. It’ll be a return, sure, but also another chance.

Because what is there for me here, now?

And these thoughts circulate as I watch the reflection of the setting sun burning brightly in the windows of the boat-yard opposite my flat, until it sinks down far enough that it disappears.

After that, the city lights, and their reflections on the water, have to work hard to pierce the darkness.

***

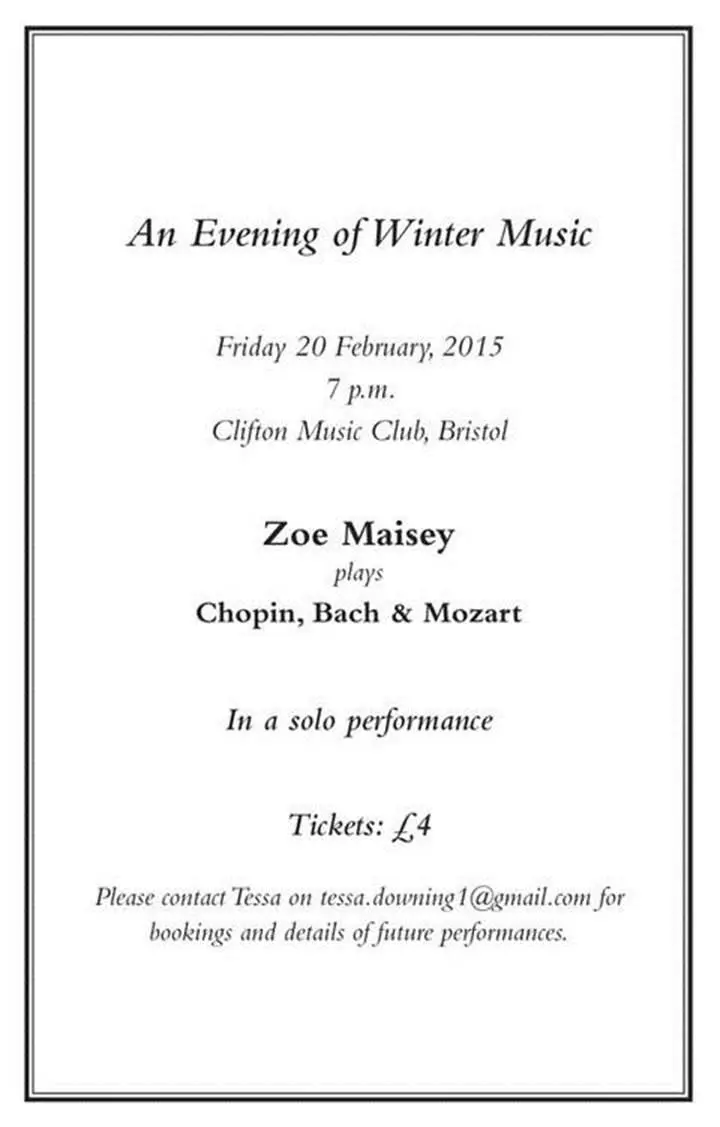

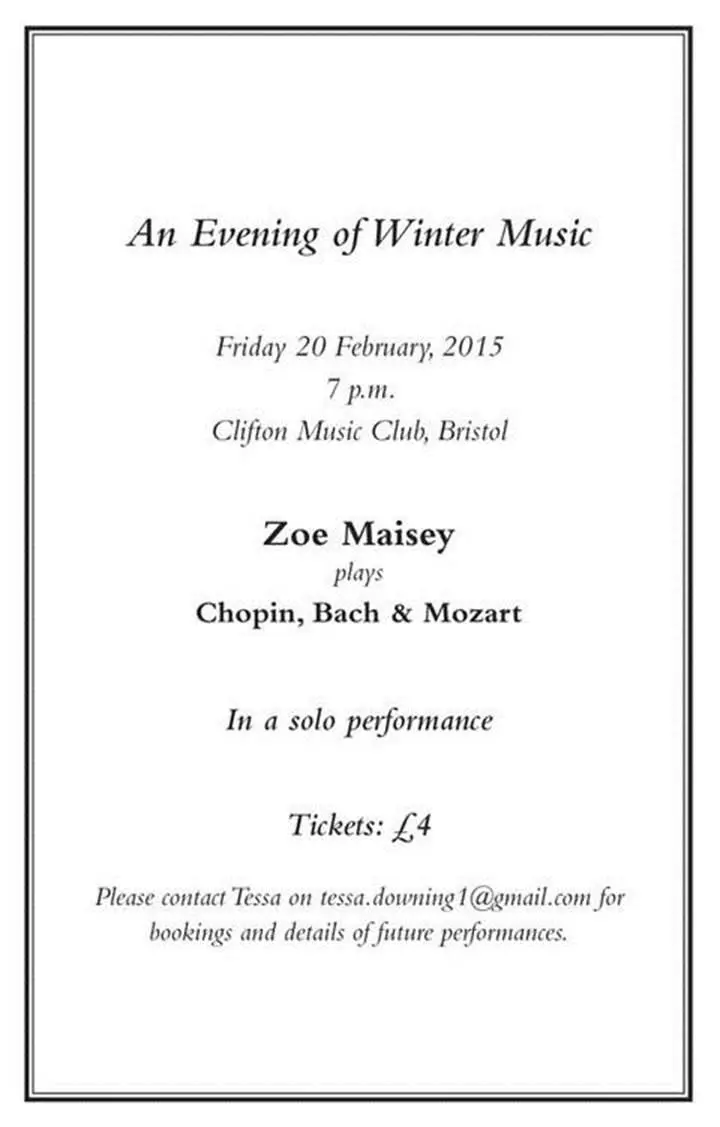

I’m standing at the side of the stage waiting to go on.

Outside there’s ice on the pavement and when we arrived Uncle Richard had to catch my arm because I nearly slipped over when we got out of the car.

Lucas is in the crowd, manning the video recorder. He doesn’t perform in public any more, though sometimes he bangs out a tune. That’s how he himself describes his playing nowadays. He’s so into filming and that’s his thing now. He spends hours watching films with Uncle Richard. Richard doesn’t make models any more, he says he never really liked them; he gets into the whole film thing with Lucas instead.

Grace is here, but we don’t think she’ll last long in the audience.

Richard says that he wouldn’t bring her along at all, but he’s sure that she’s got an unusual interest in music for a child her age. She’s captivated by my playing, he says. He’s sitting at the end of the back row with her so he has an easy exit and can take her home when she makes her first squawk. But he wants her to be here at the beginning at least. It’s my first concert since Mum died, and I think we all know in our hearts it’s a kind of tribute to her.

My piano was brought over from the Second Chance House and moved into the dining room at Tess’s house. Richard has converted his shed into a kind of cinema and film room where he and Lucas edit films and watch them on a pull-down screen.

‘It’s tech heaven,’ says Tess when she looks in there.

I tried to phone Sam once, at work, but they said he’d left, gone back to Devon. They said he was poorly. I tried to tell Tessa, but she didn’t want to talk about it. She reminded me of Mum then, pushing a subject away, lips tight and holding back feelings that I couldn’t read.

I’m playing a short programme tonight, but it contains some of Mum’s favourite pieces.

Because of the cold I’m wrapped up warmly, gloves on, and a cardigan, and I’ve been pressed against the heater that’s in the shabby little green room. We’ve been careful with the venue we’ve booked on this occasion, so very careful. It’s not a church; it’s a music club. The piano on the stage is a beautiful Steinway and there’s seating for around eighty people. This time, I shall make my entrance from the side, not down an aisle.

In my head there’s a mantra: This is your Third Chance.

I don’t think I have nine lives, but I hope I have three.

I hear my name called from the stage and, just before I go on, in my head I send a message to my mum. This is for you, Mummy, is what I think, and I have to wipe a small tear carefully from my eye.

I take off my cardigan and my gloves.

I’m looking good, in a dress that Mum chose for me before she died, a black silk dress with a high neck and three-quarter-length sleeves. I’ve brushed my hair until it’s silky, just how she would want me to. As I enter the room and mount the stage, there’s a round of applause.

Before I sit down, I do a small bow to the audience, and then the clapping stops politely. Tess is in the front row and she gives me a thumbs-up. Behind her, almost all the seats are full. My reputation has preceded me. As Chris might have said, if he hadn’t been sentenced to fifteen years in jail: No publicity is bad publicity.

Читать дальше