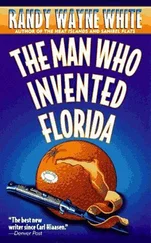

It was an odd remark. I moved a few yards along the log and selected a thick one. A lone orange plopped on the ground. “It must be the other tree,” I said.

“Nope. You found it.”

“This one?”

“All of them.”

“What do you mean?”

“The orange tree. You’re standing on it,” he said, which was even odder given his tone of disbelief. “Those are branches you’ve been shaking. Some anyway. The others, I don’t know what kind of trees they are. Come over here and see for yourself.”

I jumped down and did. It took a while to reassemble an overview of what I’d mistaken as a fallen tree amid a forest of saplings. The trunk, massive and gray-splotched, was a living giant. It had won the battle for sunlight by growing parallel to the ground and shooting branches skyward. Each branch bore leaves healthy in appearance-although some were freckled with psyllids-and most were bowed by weight and the endless production of fruit.

“Amazing,” I said, “how nature finds ways to survive.”

“Nature, yeah,” Martinez replied, his energy suddenly improved. “What I see is my retirement. This could be worth a fortune. How many people know about what you’re doing?”

I stared too long. He sensed he’d slipped up. “Now what? Oh… you’re wondering how I know about the biotech patent. Larry told me. I admire your vigilance, but, come on, enough tests for one day. I would’ve said yes to this trip anyway. I proved that back there. But now that it actually seems to be panning out-”

“I have three partners,” I said agreeably. “It’s only fair you’re the fourth. You took the risk, invested the time. They’ll sign on, I’m sure. Oh, and a friend, a marine biologist, he came up with the idea. That makes six.”

The man appeared unfazed. “Who owns this property, or whatever it is-an island? The feds or the state, I suppose.”

“Mostly. A few are privately owned.”

“We need to check that out. All righty, then. For now, we’ve got the place all to ourselves. I bet there are smaller trees around somewhere, small enough to carry home, wrapped in towels or something. They might be worth a ton, if things work out.”

“There’s a procedure, when it comes to collecting samples and DNA,” I said. “It has to be followed.”

“The correct protocols, of course, I’ll leave that to you. Did you bring a shovel? We need to take what we can before word gets out.”

There was a trowel in my bag, and a folding shovel on the boat, which I told him about.

“We should’ve brought it. One of us will have to go back,” he said. “Hang on to this for a sec, would you?”

He handed the gun to me. I levered the breech open and confirmed both barrels were loaded, while he took off his gloves. When he stooped to retie his boots, his back was to me. By the time he was standing, I had snapped the barrels closed.

“Why don’t you carry the shotgun for a while?” he said. “That sun’s warming up fast.”

I said, “You take it. Don’t stray too far. I want to get pictures and video first.”

The man was limping a little when he walked off, the shotgun under his arm.

I snapped photos with my phone, and took more as I cut my way to a ridge where the tree had first taken root. Long ago, a storm had knocked it down, but the roots had survived by re-anchoring themselves in higher ground. They looped away in various directions, as clever as the tentacles of a octopus.

I paced the tree’s length-almost fifty feet tall, if stood upright. The trunk was so thick, I couldn’t get my arms around it. A dinosaur’s neck, I imagined. I also gathered samples of leaves and bark, as instructed by Roberta. If I’d had satellite reception, I would’ve called to share the good news.

Never had I seen a citrus tree so large, and gnarled and lichen-splotched with age. How long had it survived here on the island? A tree in Tasmania, planted in 1835, was still bearing oranges-or so I’d read. A hundred years? Two hundred? Possibly, older… much older. North of Orlando was a famous bald cypress tree that had sprouted before Christ was born, and lived until 2012, when a woman crack addict set it on fire. More than three thousand years the cypress tree had survived, only to die at the hands of someone like that.

I backed up as far as I could and shot video; a slow pan along the mossy trunk, then panning the high canopy, bushels and bushels of oranges, bright as Christmas lights up there in dusty sunlight.

The mother tree.

I was thinking that when I heard the distant, rhythmic crunch of something moving, then heard Martinez, from the opposite direction, calling, “We’ve got company. Come look.”

I drew the pistol, chambered a round, and adjusted the holster for easier access.

Martinez, studying the game trail, said, “An animal of some type. Anywhere else, I would assume it was a bunch of pigs-a horse, maybe-if I even bothered to notice. What do you think?”

I had approached with caution until then. “Something’s coming our way. I heard it, too. From the south, I think, but it’s hard to be sure.”

He turned. “I didn’t hear anything. Not since that plane, or whatever it was. I found two little trees; maybe orange trees. You’re the expert.” With the shotgun, he pointed at the ground. “And this.”

It was animal scat, shaped like a football, but pillow-sized. I poked at it with my walking stick. Chunks of bone, hide, and scales were revealed; the skull of a very large snake… then the jaw and eye sockets of an alligator, medium-sized, but big enough for me to say, “It’s time to finish up and go. They’ve run out of food here. They’re eating themselves until something warm-blooded comes along.”

“Pythons,” he said, “I didn’t even know they pooped. You think it’s fresh?”

“There’re no flies on it. Maybe it was too cold for flies earlier.”

“Clever girl. Yes, get moving, but first I want to dig up a couple of trees. It won’t take long. Besides, I doubt if what you heard was-” He stopped when I held up a warning hand.

In the distance, muted by foliage, branches snapped, then snapped again after a long period of silence.

“Could be the wind,” he said. “It’s still chilly enough, reptiles wouldn’t be moving. Know what I hoped for? A big, flat rock, somewhere, and a bunch of snakes sunning themselves. That would make it easier, but there’s not a damn rock around for-”

Again, I motioned for quiet.

He listened a bit, then lowered his voice. “Yeah, just the wind. I don’t see your hurry. I mean, think about it. In a week, it’ll be like summer. Do you really want to come back another day and risk winding up like that?”

In a pile of animal scat, he meant.

It was true the wind was freshening; occasional balmy puffs from the southwest. I listened for noises a while before following him to a pair of saplings he’d found. They were scrub or water oaks, not citrus.

I thought for a moment, then said, “You know who would’ve been useful to bring along? Kermit. He knows as much as anybody about citrus.”

Martinez, not interested, replied, “Yeah, too bad about him,” then realized he might have slipped again. “Let’s face it, first Reggie, then Bigalow. You’ve got to assume the worst.”

“Two hours in a bar with Larry,” I replied. “He’s a talker. Did he say anything you might have missed?”

“About what? Oh… not about Bigalow, but, yeah, he couldn’t say enough about getting his hands on you. Seems his ego took a bruising; a love-hate thing.” Martinez’s eyes wandered; a smirk there, maybe, with a suggestive edge, as he painted me up and down. “I’ll spare you the graphics, but let’s just say he admires the cut of your jib.”

Читать дальше