Cornell Woolrich

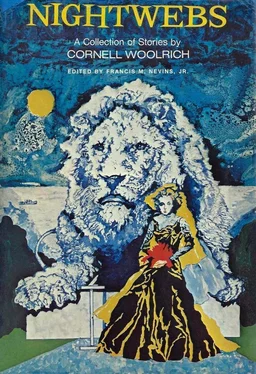

Nightwebs

(A Collection of Stories)

It was an old sneaker that started it, an old soft-soled canvas gym shoe. It rubbed his heel raw, the heel became infected and the doctor made him keep his foot elevated for six weeks. When he began to walk again, he had completed the first draft of a novel. The beginning was that simple. Except that in his unfinished autobiography he said that it was jaundice, not a heel infection, that kept him immobilized, and that he recovered long before that first draft was finished. Which is truth, which a trick of memory? Nothing is that simple.

Cornell George Hopley-Woolrich was born in New York on December 4, 1903, and spent much of his childhood traveling in Latin America with his father, a civil engineer. During the Mexican revolutions prior to World War I, he collected spent rifle cartridges — an apt hobby in view of his later career. He seems to have been shunted back and forth between parents, living with his socially prominent mother in New York during the school year but traveling with his father during vacation periods. It was not the healthiest way to go through adolescence, and it left marks on his life and his work.

In the early 1920’s he entered Columbia College, and one of his contemporaries there came to attain the same eminence as a historian of ideas that Woolrich was to achieve as a writer. Jacques Barzun attended with Woolrich both a course in creative writing and one on the novel. (The latter course was taught by Harrison R. Steeves, who himself wrote a memorable crime novel, Good Night, Sheriff, 1941.) Barzun remembers Woolrich as shy and introspective and mother-dominated even then, and as keenly interested in literature. Woolrich would have graduated with the Class of 1925, but while he was an undergraduate the incident took place that started him writing, and he left school to write full time.

Very few photographs of Woolrich exist, but an interesting verbal portrait appears in Chapter of I Wake Up Screaming (Dodd Mead, 1941), a novel by Steve Fisher who was a pulp-writer contemporary of Woolrich. “He had red hair and thin white skin and red eyebrows and blue eyes. He looked sick. He looked like a corpse. His clothes didn’t fit him...He was frail, grey-faced and bitter. He was possessed with a macabre humor. His voice was nasal. You’d think he was crying. He might have had T.B. He looked like he couldn’t stand up in a wind.” The character’s name is Cornell.

Woolrich’s first novel, Cover Charge , was published by Boni & Liveright in 1926, and even in its opening paragraph the distinctive Woolrich style is already present: “Luminaires were lit upon the walls, and from an orange dish a pencil-line of azure hung breathlessly above an expiring cigarette.” His next novel, Children of the Ritz (1927), won first prize of $10,000 in a contest conducted jointly by College Humor and First National Pictures, which filmed the book in 1929. Woolrich was invited to Hollywood to help with the adaptation. It is to be noted that one of the dialogue-and-title writers working for First National around this time was a gentleman named William Irish. [1] Irish’s name appears in the credits of three First National films of 1928—29, all directed by Benjamin Christensen: Haunted House, Seven Footprints to Satan, and House of Horror. He is not known to have worked on any other films.

While in Hollywood, Woolrich fell in love with and married a producer’s daughter who left him after a few weeks and later had the marriage annulled. Woolrich returned to New York and his mother. Four more of his novels were published: Times Square (1929), the partially autobiographical A Young Man’s Heart (1930), The Time of Her Life (1931), and Manhattan Love Song (1932). All of the early novels were heavily indebted to Scott Fitzgerald (who remained to the end one of Woolrich’s favorite authors), but are at the same time authentically Woolrichian: love is the leitmotif, and the prose approaches poetry. “Blair heard the snap of the electric light, and the lining of his flickering eyelids turned vermilion,” A Young Man’s Heart begins.

In addition to the six novels, Woolrich between 1926 and 1932 published a number of short stories, two articles and a serial in such magazines as College Humor, College Life, Illustrated Love, McClure’s , and Smart Set . But during 1933 not a single word appeared under his byline: the Depression had caught up to him. He did write another novel that year, called it I Love You, Paris , but was unable to sell it and finally threw it into the garbage, although at the end of his life he insisted that someone in Hollywood had read the manuscript while it was making the rounds and had without authorization based a movie on it. [2] Woolrich did not identify the movie he had in mind, but from his description it was probably Bolero (Paramount, directed by Wesley Ruggles, starring Carole Lombard and George Raft. According to the credits, the screenplay was by Horace Jackson from a story by Carey Wilson and Kubec Glasmon. It is impossible to tell whether Woolrich’s suspicions were justified, since the alleged source novel was destroyed.

In any event, Woolrich grew to dislike all of his work up to the middle Thirties. “It would have been a lot better if everything I’d done until then had been written in invisible ink and the reagent had been thrown away,” he commented in his autobiography.

His second chance came to him about halfway through 1934, when he turned to a new market and a new kind of story. His first mystery, “Death Sits in the Dentist’s Chair,” appeared in Detective Fiction Weekly for August 4, 1934.

There was another patient ahead of me in the waiting room. He was sitting there quietly, humbly, with all the terrible resignation of the very poor.

With these words a new creative life began; and just as Woolrich’s style was fully his own even in the first chapter of his first novel, so the motifs of his first mystery were uniquely Woolrichian. The evocation of New York City during the worst of the Depression, the integration of the Depression (in this case its effect on the dental profession) into the story structure, the outré method of murder (here cyanide in a temporary filling) — we will see them again and again in his work.

Woolrich’s two other mystery stories of 1934 are equally characteristic. “Walls That Hear You” ( Detective Fiction Weekly , 8/18/34) opens with the invasion of the demonic into the protagonist’s workaday existence, turning his life into sudden nightmare as he finds his younger brother with all ten fingers cut off and his tongue severed at the roots. “Preview of Death” (Dime Detective, 11/15/34) is distinguished by its movie-making background (films being a recurrent element in Woolrich) and another unusual mode of murder (setting fire to an actress in a flammable Civil War hoopskirt).

The ten crime stories Woolrich published in 1935 were of uneven quality but incredible variety; together they expressed almost all of the motifs and beliefs and devices that form the nucleus of Woolrich’s fiction. “Murder in Wax” ( Dime Detective , 3/1/35) is his earliest attempt at first-person narrative from the viewpoint of a woman. “The Body Upstairs” ( Dime Detective , 4/1/35) is a straight detective story marked by casual police brutality and by intuition passing for reasoning in the solution. “Kiss of the Cobra” ( Dime Detective , 5/1/35) is another tale of the demonic invading ordinary life, ridiculous in conception (the narrator’s widowed father-in-law brings home as his new wife a Hindu snake-priestess complete with instant Dr. Grimesby Roylott kit), but with a climactic scene involving the smoking of poisoned cigarettes that is pure Woolrich. “Red Liberty” (

Читать дальше