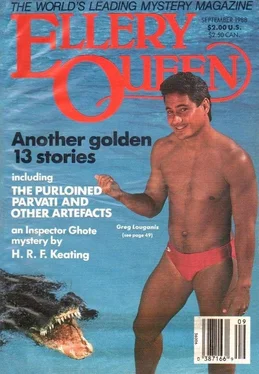

William Bankier - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Bankier - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1988, Издательство: Davis Publications, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988

- Автор:

- Издательство:Davis Publications

- Жанр:

- Год:1988

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The man stood and extended a hand to Sussock. He had a warm, beaming face behind heavy-rimmed spectacles. Sussock, after his brief bad first impression at the porter’s lodge, was beginning to like the staff at the Vicky. “Paxton, Mr. Sussock,” said the man, shaking Sussock’s hand. “Please take a seat.”

Sussock sat. He thought Paxton was about as old as himself — sixty this year — but he looked to be fitter than Sussock — with his bad chest, a legacy of years of cigarette smoking — felt himself to be. But police work had helped Sussock to remain slim. Paxton was swelling noticeably about his middle and his face, though by his cheery manner it was clear that he wasn’t at all embarrassed by it. They had, Sussock thought, probably led a parallel existence in the city, though they were now meeting for the first time. How often in the last sixty years, he wondered, had they shared the same bus, passed each other in the town, shivered on the same cold days?

“What can I do for you, Mr. Sussock?” Paxton asked. “I gather you have called about the dreadful incident yesterday?”

“In respect to Mr. Skillicorn, sir? Yes, that’s why I’m here.”

“He’ll be a sad loss to the hospital. He was a good doctor, a good obstetrician.”

“He was a colleague of yours?”

“Well, he was a colleague of all of us. A hospital is like a ship — it doesn’t work unless we all play our part, from the captain on the bridge down to the chap who stokes the boiler. But I know what you mean. I daresay I worked more closely with him than anyone else.”

“He was murdered,” said Sussock. “His house wasn’t ransacked, there was no robbery, no forced entry. The murder took place when Mrs. Skillicorn was out of the house, which indicates that the murderer may have been watching the house, waiting for the moment to strike.”

“That’s chilling,” Paxton murmured. He sat back in his chair and slipped his spectacles off and laid them on the desk. “We knew he had been murdered, but I confess we know no details.”

“He seems to have been murdered for a personal reason.”

“Well, I can assure you he had no enemies in the hospital.”

“What about outside?”

“I know little of his personal affairs.”

“I see.” Sussock took out his pad and began to take notes. “What about his relationship with his patients?”

Paxton shuffled uncomfortably. “Well—” he put on his spectacles “—he was recently subject to a complaint.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. Not what I would call serious in nature. It was a question of alleged misconduct rather than negligence. He put up a defense and the British Medical Authority upheld his defense. In a nutshell, he terminated a pregnancy. The woman in question was psychiatrically ill. She suffered bouts of depression — not by any means acute enough to warrant her admission to hospital, but it was a significant illness. She asked her G.P. for a termination and the G.P. considered her to be sound enough of mind to know what she was asking. Hugo also spoke to her, and on the strength of the G.P.’s view and on his own discussion with her agreed to perform the termination. Weeks later, the husband — she was a married woman — the husband came storming in here, rowed with Hugo, and stormed out again. Then he made the complaint and, as I said, the B.M.A. upheld Hugo’s defense. That was the last we heard of it.”

“So the husband didn’t know anything of his wife’s termination before the fact?”

“No.” Paxton took off his spectacles again. Sussock had the impression Paxton wore his glasses when he felt under threat and took them off when he felt on firmer footing. “It isn’t a requirement in law nor is it a requirement in the National Health Service guidelines which we follow. We pursue a policy of the woman’s right to choose. I daresay it’s not wholly ethical to keep the husband in the dark, but it’s a dilemma that crops up in other areas of medicine. When should a doctor violate the confidentiality of the relationship with a patient? What does the family doctor do when the fifteen-year-old daughter of a patient asks for help with birth control? Does he give advice, in which case he is colluding with underage sex, or does he notify the girl’s parents, in which case he has violated the relationship with his patient, which ought to be as confidential as a confessional?”

“It’s not easy, is it?”

“It isn’t — and often as not, a termination is requested in order to save a marriage.”

“To save it?”

“Yes. If, for example, the father of the unwanted child is not the woman’s husband and for a variety of reasons the husband knows the child could not be his, that is something we would rather not be involved in. We believe that if the husband or father of the child should be informed, it is the responsibility of the woman to inform him. She has the right to choose termination, and she also has the right to decide whether the father of the child is to be notified. You may think sterilization is the male equivalent, but because it is virtually irreversible, we require the full consent of a wife before sterilizing a husband.”

“But abortion—”

“I don’t like that word.”

“I’m sorry — termination, then. That is entirely the woman’s decision?”

“Yes. It’s an emotive subject. We won’t terminate beyond the thirteenth week, when we deem the fetus to be alive, unless the mother’s health is in danger, and we won’t terminate if the woman is not of sound mind when she asks for the termination.”

“Which in this case she was — I mean of sound mind.”

Paxton’s eyeglasses were on again. “We were aware of her depressive episodes, but Hugo and the G.P. believed she still was able to retain a grasp of the issues. It may even be that Hugo and the G.P. felt that the danger of postnatal depression, on top of an already present depressive illness, would have been fatal for both mother and child, and as the woman in question was still well within her childbearing years a good argument could be made for allowing her time to recover from her illness before continuing to have her family.”

“Continuing?”

“She had two children already. Two kids, a difficult husband apparently, depression — not to be dismissed as an illness — an unwanted pregnancy for whatever reason. Yes, I can see why the G.P. and Hugo felt that termination was a reasonable request to accede to.”

“You certainly make a good case, Dr. Paxton, even to a layman.”

“Well, I think it was the illness that clinched it. Even otherwise-healthy mothers have been known to throw their babies out of the window when suffering postnatal depression. In some cases they follow the child down, so that it becomes a double tragedy. In this case, it seemed reasonable to agree to the termination.”

“Can I have the lady’s name, please?”

Paxton leaned toward his desk, shuffled some files, and selecting one. “Muirhead, Jean,” he said. “Aged twenty-five, address in Castlemilk.”

Donoghue phoned the Press Office and requested a press release: The Maxwell Park murder, Sunday between 1500 and 1700 hours, the murderer probably heavily stained with blood, did you see anybody, did anybody come home to your house or your neighbor’s house like that?

“That sort of thing,” said Donoghue. “I’ll leave the exact wording up to you, but will you clear the final copy with me before you release it? Thank you.”

From the Victoria Infirmary, Sussock drove the short distance to a house in Langside. He climbed the stairs and stopped when he came to a door marked WILLEMS. He tapped on the door. When she opened it, she had changed out of her uniform and her blonde hair was down about her shoulders. She was dressed in a short brown mini-robe that revealed her long slender legs. Behind her, in a recess just off the kitchen, steam was pouring from the shower cubicle.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 92, No. 3. Whole No. 547, September 1988» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.