Where? he thought.

And turned, hoping he would not get shot in the back, after all, because getting shot in the back would be a first for him. On Christmas Day, no less. Which would not be such a terrific surprise since he seemed to be experiencing a great many firsts here in festive New York City, the least of which was being attacked by a ferocious movie star who now looked not like Marilyn Monroe but that lady, whatever her name was, in Fatal Attraction with the frizzed hair and the long knife in her hand.

Jessica did not have a knife in her hand.

Jessica had a poker in it.

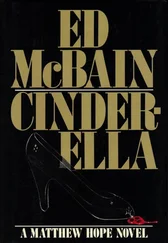

Which she had grabbed from a little stand alongside the fireplace, leaving a shovel and a brush still hanging from it. She came limping at Michael, one shoe on, one shoe off, her lips skinned back, her capped movie-star teeth glistening with spit, her eyes blazing. He figured she was angry because he’d knocked her on her ass.

But then Crandall put a very clear perspective on the entire situation.

“Careful!” he shouted. “He’s a killer!”

And Michael realized in a dazzling epiphany that Crandall either really believed he had murdered someone, or else was putting on a damn good show of believing it. Convincing Jessica — who did not seem to need very much convincing — that Michael was an armed and dangerous murderer, and this was a simple matter of survival. Which explained the desperate look in Jessica’s eyes and the headlong rush at him with the poker. But which did not explain why Crandall stood there with a weapon in his hand and his thumb up his ass.

Michael had never hit a woman in his life.

When he’d learned about Jenny and her branch manager, he’d wanted to hit her, but then he’d wondered what good that would do. He’d already lost her. James Owington had already taken her from him, so what was the sense of hitting her? Wouldn’t that be more punishing to him than it would be to her? The eternal knowledge that he had hit a woman who was only five-feet six-inches tall and weighed a hundred and twenty pounds? Who wasn’t even working for the Viet Cong?

Jessica wasn’t working for the Viet Cong, either.

She was merely a sensible woman trying to save her own life. She had a good cheering section, too. As she came at Michael, the poker swinging back into position, Crandall whispered little words of encouragement like “Hit him, kill him!” From the look on her face, she needed no urging. Crandall had warned her that Michael was a killer; unless she took him out, he would kill again. The thing to do now was knock off his head. Before he knocked off hers.

Which Michael did.

He hit her very hard.

There was nothing satisfying about the collision of his fist with her jaw. He hit her virtually automatically, bringing his fist up from his knees as if he were throwing an uppercut at a sailor in a Saigon bar, repeating an emotionless action he had gone through at least a dozen times before, unsurprised when he heard the click of teeth against teeth, unsurprised when he saw her eyes roll back into her head. He watched as she collapsed. One moment she was standing, the poker back and poised to swing, and the next moment she folded to the floor as if someone had stolen her spine.

Michael walked to where Crandall was standing with the gun in his hand.

“Fuck off, okay?” he said, and took the gun from him and went to the door.

He now had two guns.

Like a Wild West cowboy.

One in each pocket of his coat.

He was happy that the two uniformed cops who came up the steps as he was going down did not stop and frisk him.

“Are you looking for the guy beating his wife?” he asked.

“No, we’re looking for Wales,” one of the cops said.

“That’s near England, I think,” Michael said, and continued on down.

Connie was waiting outside in the limo, the engine running.

“I think it’s time we went home,” she said.

She drove the limo to the garage China Doll used on Canal Street, and they began walking from there to her apartment on Pell. As promised, the temperature was already starting to drop. Michael guessed it was now somewhere in the low twenties or high teens. They walked very rapidly despite the packed snow underfoot and the occasional patches of ice on sidewalks that had been shoveled, their heads ducked against the wind, Connie’s arm looped through his. Under the other arm, she carried the green satin high-heeled shoes she’d retrieved from the limo’s trunk. The streets were deserted. This was four o’clock on Christmas morning, and everyone was home in bed waiting for Santa Claus. But Michael was brimming with ideas.

“What we have to do is find out where Charlie Nichols lives,” he said.

“Okay, but not now,” Connie said. “Aren’t you cold?”

“Yes.”

“I mean, aren’t you freezing ?”

“Yes, I am. But this is important.”

“It’s also important not to die in the street of frostbite.”

“You can’t die of frostbite.”

“For your information, frostbite is freezing to death.”

“No, it’s not.”

“Can you die of freezing to death?”

“Yes.”

“All right then,” she said.

“Connie, the point is we’ve got to talk to Nichols. Because if he’s the Charlie in Crandall’s calendar...”

“Please hurry.”

“Then maybe he can tell us who Mama is, or why Crandall drew nine thousand dollars from the bank, if he did, or what he did with that money, or what his connection is with the two people who took all that stuff from my wallet and the one who stole my car.”

The words came out of his mouth in small white bursts of vapor. He looked as if he were sending smoke signals. The clasps on Connie’s galoshes clattered and rattled as she led him through yet another labyrinth, this goddamn downtown section of the city was impossible to understand. None of the streets down here were laid out in any sensible sort of grid pattern, they just criss-crossed and zigzagged and wound around each other and back again, and they didn’t have any numbers, they only had names, and you couldn’t get anywhere without a native guide, which he supposed Connie was. A very fast one, too. She walked at a breakneck pace, Michael puffing hard to keep up, both of them sending smoke signals with their mouths. He hoped there weren’t any hostile Sioux on ponies in the immediate neighborhood. He would not have been surprised, though. Nothing that happened in this city could ever surprise him again.

They came at last to a Chinese restaurant named Shi Kai, just off the corner of Mott and Pell. The restaurant was closed, but a sign in the front window advised:

OPEN FOR BREAKFAST

AS USUAL

CHRISTMAS DAY

Connie took a key from her handbag, unlocked a door to the left of the restaurant, closed and locked it behind her, opened another door that led to a flight of stairs, and began climbing. There were Chinese cooking smells in the hallway. There were dim, naked light bulbs on each landing. She kept climbing. Behind her, he watched her legs. Her galoshes rattled away. He hoped they wouldn’t wake up anyone in the building. On the third floor, she stopped outside a door marked 33, searched in the dim light for another key on her ring, inserted it into the latch, unlocked the door, threw it open, snapped on a light from a switch just inside it, and said what sounded like “Wahn yee” or “Wong ying,” Michael couldn’t tell which.

“That means, ‘Welcome’ in Chinese,” she said, and smiled.

“Thank you,” he said, and followed her into the apartment.

He supposed he’d expected something out of The Last Emperor. Sandalwood screens. Red silk cloth. Gold gilt trappings. Incense burning. A small jade Buddha on an ivory pedestal.

Читать дальше