At night, with the television, I felt as though this house were mine.

But one night Mrs. Kent came down the stairs. Mr. Kent had sent me into the kitchen for a fresh bucket of ice. I heard her voice and waited in the entry, behind the swinging door.

“Paul — I thought I heard someone talking. What are you doing down here?”

He answered loudly. I think he wanted me to hear. “The TV. Just watching the TV.”

“Oh. Hadn’t you better go to bed? You’ve been drinking again. That isn’t helping you find a job, or write that book you keep talking about either.”

I heard him move. His voice got thick, like it was sometimes when he was with me on the sofa.

“Can I sleep in your room, Karen?”

“No. Not tonight. You know I can’t abide the smell of liquor.”

“No — you can’t, can you?” He stomped angrily across the room and I heard a click as he turned the television off. “In fact, you can’t really abide me, can you, Karen?”

“Not very often, Paul.” Her voice cracked like ice on the river.

I heard the loud sound and I pushed open the door to look. He had hit her and she fell as I watched, slowly, like a slow motion scene in an old movie. Her head made a funny noise against the bricks of the fireplace. We’d had watermelon once at the institute and somebody dropped one. It sounded like Mrs. Kent’s head did when it hit. Splonk.

He drew back, his mouth open, but making no sound. He leaned down over her and raised up. He looked around and I was careful to keep out of sight. He took a long taste from the bottle. Then he took hold of her feet and pulled her behind the sofa next to the wall. He pushed the sofa back over her. He went to the bathroom and brought a wet towel. He wiped the bricks. He took the towel away.

I was in the living room when he came back. The ice was on the table. I was turning the television set on.

He put his hand on mine and turned it off.

“How would you like a little vacation, Julia. A couple of weeks at the beach? In the city? Anywhere, anywhere at all.”

I kept my eyes down and my hands clasped lady-like behind me.

“I don’t think Miss Ascot would let me go.”

“Damn Miss Ascot.” Little beads of sweat stood out on his brow. He was thinking, hard. It was like watching a play — he was looking for a way out.

I poured him a drink. “Here, Mr. Kent. You don’t look so good. This will make you feel better.”

His hand went around the cold glass. His round blue eyes looked at me and suddenly they became flat and narrow.

The phone rang and he answered it. He talked for a while out in the hall and then came back. He didn’t know I went to the kitchen. He raised the glass to his lips; I knew Mr. Kent had found a way out.

He’s lying beside her now. I found the package high on a kitchen shelf where Mrs. Kent had told me to put it, away from the children. Rat poisoning, it said, with a red skull and crossbones. While Mr. Kent was out at the phone I put it into the whiskey.

He knew, I think, right away but he’d taken a huge swallow the way he always did and it was too late. It didn’t take long after that. It was easy, even for me, to see Mr. Kent’s only way out. Blame it on the hired girl. I’d seen that done on television at least a dozen times.

I wiped off fingerprints and put glasses in their hands — just long enough to leave their marks.

As soon as Steve Allen is over, I’ll go to bed.

Somebody will find them by morning. I hope the next house I go to has color. Twenty-four inch.

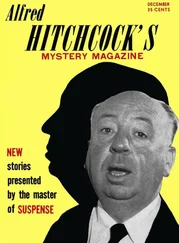

Originally published in AHMM, February 1957, as by DeForbes. Copyright © by H.S.D. Publications, Inc., © renewed 1985 by Davis Publications, Inc. Reprinted by permission of the author.