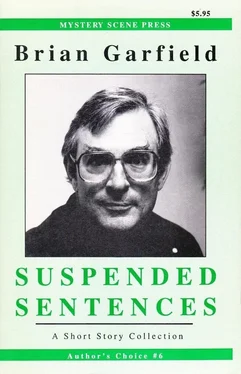

Brian Garfield

Suspended Sentences

Writing introductions to one’s own stories is at best an exercise in awkwardness (if this isn’t self-promotion, what is?) and at least an exercise in redundancy (if a story cannot stand on its own, without explanatory introduction, then isn’t it inadequate?).

So I hope you will forgive my cowardice in trying to steer a course that avoids both the foregoing hazards. In the prefatory notes that accompany each story I’ll abstain from discussion of the story itself and thus try to avoid the temptation to defend or boast. Instead, I’ve tried to address the circumstances that inspired or provoked each story.

Most of these were written during or shortly after trips to the locales in which the stories are set. Most of them were written by hand in notebooks while on airplanes or beaches or in hotels; later at home I would type and revise them.

Short stories are harrowing: for some of us they are precarious and difficult and unforgiving, which may explain why I have written twice as many books as short stories. For this paucity please grant the excuse, if you will, that there are very few markets for short stories and even fewer markets that pay enough .

(Do not ask for a definition of enough . To a writer there is no such thing as enough. )

As to subject matter, my short stories fall mainly into three categories. There are espionage stories, collected in the book CHECKPOINT CHARLIE a few years ago; there are Western stories, anthologized hither and yon but not yet collected in one place; and there are crime-suspense stories, most of which are gathered herein. Some of the tales overlap more than one category because my background is in the American West and so that is where many of the yarns are situated.

I’m grateful to Ed Gorman for suggesting that we compile these stories and for having the nerve to publish this volume.

“The Gun Law” is a narrative reconstruction of an actual incident. The main character was an acquaintance of ours, and we shared the suspense and fears of his arrest and incarceration. The case was decided in court just as is represented here. Occasionally real life does make serviceable fiction .

Deke Allen was arrested Friday afternoon on his way home from his uncle’s house in Yorktown Heights.

He’d had a call that morning from his father. Mostly just to ask how Deke was doing, how was business, how’s that girl what’s-her-name, the one you live with, pretty little thing. So forth. But during the call his father mentioned that Uncle Bill was having a problem with rats in his basement. Deke’s father said, “If you happen to be heading up that way you can drop by and pick up my shotgun. Take it on up to Bill’s and see if you can take care of those rats for him.”

Uncle Bill didn’t like to put down poison because he had a houseful of dogs. He adopted stray dogs; it was his avocation. The place — a four-acre farmstead near the Croton Reservoir — was fenced in to contain the cacophony of orphaned dogs. Deke liked Bill and had nothing better to do that Friday. His next job wasn’t scheduled to start till Monday. So he went by his father’s house in Ossining and picked up the pump-action sixteen-gauge and a boxful of shells for it, and drove out along Baptist Church Road to his uncle’s dog farm.

Deke Allen tended to carry just about anything a human being might need in his Microbus. It was his factory, craft-shop, tool-warehouse, and repair center. Deke, in his anachronistic two-bit way, was a building contractor. He specialized in restorations of old houses, preferably pre-Revolutionary houses; there were plenty of them in the Putnam County area and he had a good deal of work, especially from young New York City couples who’d made themselves a little money and moved to the country and bought “handyman special” antique houses for low prices, hoping to meet the challenge. Most of them learned that it was harder work than they’d thought; most of them had city jobs to which they had to commute and they simply didn’t have enough time to repair their old houses. So when an old cellar sprang a leak or an old beam needed shoring up or an old wall crumbled with dry-rot, Deke Allen would arrive in his Microbus with his assortment of tools. Most of them were handmade tools and some of them actually dated back to Colonial times. He was especially proud of a set of old wooden planes. He’d had to make new blades for them, of course, but the wooden housings were the originals — iron-hard and beautifully smooth and straight. And he carried buckets filled with old squarehead nails and other bits and pieces of hardware he’d retrieved from condemned buildings and sheriff’s auctions and the Ossining city dump.

He kept all his toolboxes and hardware in the Microbus; he’d built the compartments in. He even had a little pull-down desk in the back where he could do his paperwork — measurements, billings, random calculations, the occasional poem he wrote. He kept an ice cooler in the back for soft drinks and beer and the yogurt he habitually consumed for lunch. Deke was a health-food nut. The only thing he never carried in the truck was marijuana; he knew better than that. Show a state cop a psychedelically painted Micro-bus driven by a young-looking 25-year-old with scraggly blond hair down to his shoulder blades and a wispy yellow beard and mustache and a brass ring in his left ear — show a state cop all that and you were showing him a natural reefer repository. So the grass never went into the Microbus. And he was always careful to carry only unopened beer cans in the ice cooler. It was legal so long as it was unopened. Deke got rousted about once every three weeks by a state cop on some highway or other. It was an inconvenience, that was all. You had to put up with it or get a haircut and change your lifestyle. Deke wasn’t tired of his lifestyle yet, not by a long shot. He liked living in the tent with Shirley all summer long. Winters they’d spring the rent for an apartment. This was March; they were almost ready to move out of the furnished room-and-a-half; but they were still living indoors and that was why his father had been able to reach him on the boarding-house phone.

This particular Friday he went on up to Uncle Bill’s dog farm and went inside with the shotgun. They took a lantern down into the dank basement and they sat down until the light attracted the rats. They’d put earplugs in; it was the only way to stand the noise in the confined space. When Uncle Bill judged that all the rats were in sight, Deke handed him the shotgun and Bill did the shooting. Deke didn’t like guns, didn’t know how to shoot them, and didn’t want anything to do with them. He was lucky he’d been 4-F or he’d probably have dodged the draft or deserted to Canada. It was one moral decision that hadn’t been forced upon him, however, and he was just as happy he hadn’t had to face it. He was half deaf, it seemed, the result of too much teenage exposure to hard rock music at too many decibels. Deafness qualified you for a 4-F draft status. It also made life fairly miserable sometimes; he wasn’t altogether deaf, not by a wide margin, but there were sounds above a certain register that he couldn’t hear at all and he generally had to listen carefully to hear things that normal people could hear without paying any attention. Conversation, for example. If he looked at TV — which wasn’t often, since he and Shirley didn’t own one — he had to sit close to the set and turn the sound up to a level that was uncomfortably loud for most other people in the room.

But he could hear it all right when Shirley whispered in his ear that she loved him.

Читать дальше