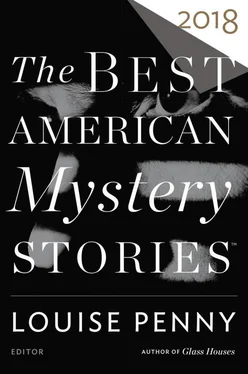

Майкл Коннелли - The Best American Mystery Stories 2018

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Майкл Коннелли - The Best American Mystery Stories 2018» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Mariner Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Best American Mystery Stories 2018

- Автор:

- Издательство:Mariner Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-544-94909-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Best American Mystery Stories 2018: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Best American Mystery Stories 2018»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Best American Mystery Stories 2018 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Best American Mystery Stories 2018», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Sorry, Fender,” I whispered aloud.

Theresa’s eyes opened a crack and she muttered in a dreamy voice, “Where are you going?”

“I’ve got a few things I need to do today,” I said. “Go back to sleep. I’ll call you later.”

“I don’t want you to go,” she said, but she was already closing her eyes and drifting away.

“Theresa,” I said. “Don’t go anywhere. Don’t trust anyone. Don’t answer your door. Not until I call you.”

“Okay,” she said, but she seemed asleep already.

When I left, I locked the door handle but had no way of locking the deadbolt unless I woke her up to do it. I thought about it, and decided to let her sleep.

My apartment lived somewhere in the world between Fender’s and Theresa’s: not as shitty as hers, not nearly as nice as his. It was a modest two-bedroom with a nice TV and decent furniture.

I opened my backpack and put both bags of drugs on my wooden coffee table.

I stared at the Y.

Did Ramzen kill Fender?

Probably.

That meant the smart thing to do—smart for me but also smart for Theresa—was to hand the stuff over to him. That was the easiest way to stay safe, and to keep Theresa safe.

But Fender was my oldest friend, which pretty much made him my best friend. We didn’t have much in common anymore, but I liked him more than most people.

And I was in love with his sister.

I admitted that to myself at that moment, with the dull dawn light coming in through the window making the powder in the Y bag look even more gray and ashen.

I told you before I often did stupid things, impulsive things. You could say sleeping with Theresa hours after her brother was killed might be one of them.

But there was an even dumber thing I felt like doing.

I wanted to try the Y.

I kept telling myself that I would be able to think better if I knew what I was dealing with. Was this some great revolutionary new drug? Or just ordinary coke with a made-up story to go with it?

I wasn’t sure how knowing the answer would help me, but I felt like it would.

Or maybe I was just rationalizing. I wanted to try the Y, and so I convinced myself it was a good idea.

I got a drinking straw from the kitchen, cut off an inch section of it, and went back to the living room. When I opened the bag, there was a peculiar smell. Like a dusty book sitting on a shelf for a couple decades, with another underlying scent barely hidden—a rotten smell, like roadkill.

I stuck the straw into the bag, put the other end to my nose, and snorted a good, hard pull.

The effect was instantaneous.

It felt like I’d inhaled fire, and the flames spread through my skull and down into my limbs. I thought I was going to die, and then the pain turned into a soothing warmth. I sank back into the couch like I was falling into an ocean of pillows. I just kept sinking and sinking, my fingers and toes numb, the rest of my body nonexistent. I closed my eyes and began to dream.

I wasn’t human. My heart was pounding, my breathing coming out in raspy, ragged bursts. I had big powerful legs and tiny little arms, and a long tail that balanced the weight of an enormous skull. I had a massive snout and teeth the size of kitchen knives. It felt natural to have this body, to have this balance.

I was running through a jungle of exotic plants. My sense of smell was stronger than any human’s, and I inhaled rich, wild scents that I’d never experienced before.

It was intense, this dream, so lucid that I didn’t want to open my eyes and risk dissolving it.

I don’t know if it was the power of suggestion making me see what I was seeing and feel what I was feeling. Just knowing the story behind Y could have been enough to tell my brain what dream to have. Opiates can work that way.

But it didn’t feel that way at the time. I felt like whatever was in the Y had transported me back—mentally, telepathically, supernaturally—to a time millions of years ago. When the world was embryonic and the animals were primal, instinctual, murderous. I could feel the stardust in my bones, the atoms that were once plants or animals or water. I was the world and the world was me.

In the dream I killed some smaller creature, a feathered, four-legged little dinosaur. I ripped it apart with my sharp teeth, and I woke up with the coppery taste of blood in my mouth.

I staggered to the bathroom, unsure how to walk without a tail. I slurped water from the sink and looked at myself in the mirror.

There was a little splotch of dried blood around my nostril.

I checked the time. Six hours had passed.

I rushed out the door and headed for the bar. Theresa and I were both scheduled to work tonight, and I needed to find people to cover for us. The employees’ numbers were tacked up behind the bar. I didn’t have them with me.

There was no way I was working, and I wasn’t leaving Theresa alone either.

I didn’t feel any closer to having a plan about what to do, and I wasn’t sure if it was a good idea to tell Theresa how powerful the stuff was, given her drug history. But I felt like I should tell her. Her brother had died for this stuff. She had a right to have a say in what happened. And if I’m honest, I pictured us snorting the stuff together. It was that good.

I called her, but there was no answer.

When I walked into the alley behind the bar, Zakir’s black BMW was sitting there idling.

His arm was sticking out the open window, holding a cigarette.

“Hey,” I said, acting as if nothing out of the ordinary was happening.

“Where’ve you been?” he said. “You need to open soon.”

“Having a rough morning,” I said. “You heard about Fender?”

“Yeah,” he said. “Tragic.”

He said the words as unemotionally as if he was reporting on some crime on the other side of the planet.

He pitched his cigarette into the alley and followed me inside.

I poured him his single-barrel bourbon on the rocks, like always—when he wasn’t accompanied by Ramzen, that is.

He threw it back and slurped it all down.

“Another?”

“No.”

He reached into his sports jacket. I thought he was going to pull out a pistol, but instead he pulled out a switchblade.

The same pearl-handled one from Fender’s safe.

He poked around in the ice of his glass. There was blood on the blade, and tendrils of red spread into the liquid remnants at the bottom of the glass.

He fished out a piece of ice and popped it into his mouth. He crunched on it like candy. Then he folded the knife and stuck it back in his coat. His hand came out with a plain white envelope.

“Open this after I leave,” he said.

“What is it?”

“I’ll be back when you close tonight,” he said. “You give me what I want. I give you what you want.”

I scrunched my nose to pretend that I didn’t know what he was talking about.

As he walked toward the door, he called over his shoulder, “Don’t get any smart ideas. Don’t call the cops. Don’t call Ramzen.”

I said nothing. But I understood. He was going behind Ramzen’s back.

When he was gone, I tore open the envelope. Inside was a small plastic sandwich bag, and inside that was a tiny severed toe.

With ugly purple paint on the nail.

I called in a waitress and a bartender, and I made them do most of the labor while I sat in my office. I let them each go an hour early, and then I told the few remaining customers that I needed to close early.

When Zakir came in with Theresa, I was sitting at the table she and I had used the day before, first to share a joint, then to talk to the cop.

Theresa was limping. She had on black Nike running shoes, and it looked like the toe area on one foot was wet.

Zakir shoved her roughly into a chair and sat down across from me.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Best American Mystery Stories 2018»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Best American Mystery Stories 2018» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Best American Mystery Stories 2018» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.