“Lloyd Davis,” Matthew said.

“Very clever what you did, both of you, getting that confession out of him without making it seem like entrapment. Very clever. Interesting case, that one.”

What Bloom still referred to as the “Beauty and the Beast” case, but what Matthew would always think of as the George Harper tragedy. A long time ago. Water under the bridge. Bannister had been an ally then. Now he was an adversary.

“I asked you then — do you remember, Matthew? — I asked you if you were thinking of entering the practice of criminal law, do you remember? And you said, correct me if I’m wrong, you said, ‘Not particularly.’ ”

“I remember.”

“And I said, correct me if I’m wrong, I said, ‘Don’t, I’ve got enough troubles getting convictions as it is,’ or words to that effect, if I recall correctly.”

“You do.”

“So now you are practicing criminal law,” Bannister said, and sipped at the wine again. “And you are representing a man charged with a heinous crime, Matthew, a heinous crime, and it is my duty to send that man to the electric chair. As much as I like and admire you, Matthew.” He shook his head morosely. “That’s what’s so difficult about my job.”

“Don’t worry,” Matthew said. “You won’t have to send him to the chair.”

Bannister looked at him boozily, fuzzily, and querulously.

“I plan to see that you don’t,” Matthew said.

“Ah, Matthew,” Bannister said, “good, true Matthew,” and recklessly threw his arm around the back of Matthew’s chair and onto Matthew’s shoulders. “I hope so, I sincerely hope so. Nothing would give me greater satisfaction than to have you prove we’ve made a grievous error here, Matthew, a grievous error. Your first important case, I know how dedicated you must be to proving your client innocent of the crime as charged, a heinous crime.” He picked up his glass again, sloshing a bit of wine onto the black silk lapel of his jacket. “But why are we talking such mordred talk, Matthew, morbid? Have some wine, let’s toast the holiday season and peace on earth to men of good will. Okay, Matthew? Some wine, Matthew?” He picked up the bottle with his free hand. “No hard feelings, Matthew?”

“No hard feelings,” Matthew said.

Holding his glass in one hand and the bottle in the other, Bannister sloshed wine onto the table from both glass and bottle, and finally found Matthew’s glass. “There we go,” he said. He put the bottle back on the table. He lifted his glass. “Here’s to justice,” he said.

Bullshit, Matthew thought.

“Here’s to justice,” he said, and drank.

For somebody who was supposed to be such a smart businessman, Henry Gardella had made a lot of mistakes.

“I don’t want to be bothered with bills,” he’d told her.

That was his first mistake, and his biggest one.

“We’ve worked out a budget,” he’d said. “A hundred and seventy-five grand, including your bonus on delivery. If you bring in the movie for less than that, terrific, buy yourself a new car. I don’t want to see bills, I don’t want to know what you’re paying your actors, or how much it’s costing you at whatever lab you use, that’s your business. My business is, I want the film made for no more than what I’m paying for it, and I want it delivered on time. You said Christmas, I want it by Christmas. You go over budget, you fail to deliver for one reason or another, then you don’t get the twenty-five-grand bonus, and I get everything you shot to turn over to somebody else to finish. That’s it.”

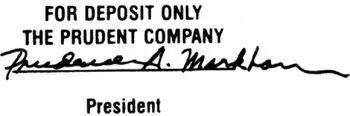

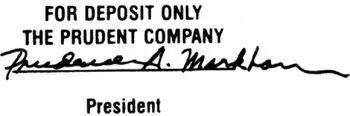

His second mistake was writing a check to the Prudent Company each and every week while she was working. He had figured this was the smartest way and the safest way to do it. He didn’t want any of the Miami boys to trace back lab bills or studio bills or any kind of bills to Henry Gardella, who if they knew he was financing a porn flick would maybe come around to break his eyeglasses. The Prudent Company could have been anything, it didn’t have to be a movie company. In fact, it sounded like an insurance company.

Also, there were laws about making pornography, and he didn’t want some bright boy working in a lab someplace in Atlanta or New York looking at all those dirty though stylish moving pictures and saying to himself, Gee, these checks are coming from the Candleside Dinner Theater in Miami, Florida, and they are being signed by a Mr. Henry Gardella, so maybe I ought to drop in on him and hit him up for some change unless he wants everybody in the world to know he’s violating Chapter 847 of the Florida Statutes, which is a crime punishable by up to a year in jail and a possible thousand-dollar fine. Better the guy should go to Prudence Ann Markham of the Prudent Company and hit on her. Henry wanted his hands to be clean.

So each and every Friday, a check for twenty thousand and some change went out to the Prudent Company at a post office box in Calusa. If she was as honest as he thought she was — for Christ’s sake, she looked like a minister’s wife! — then she was shooting the film and paying her crew and her actors and her food charges and her immediate lab bills and whatever else from the checks he sent her. Which at the end of five weeks and three days came to a hundred and five thousand bucks. Before she got herself killed, he still expected to pay for all the heavy lab work when she finished her editing and turned in her cut — the mix, the blowup, the answer print, the color composite, all that technical shit. That would have come to another forty-five K, which thank God he hadn’t yet given her, but which would have brought the total to a hundred and fifty thousand, which was just what he’d figured in the beginning. Plus the twenty-five bonus on delivery.

The canceled checks had come back to him in Miami:

Plus the bank’s stamp someplace on the back of each check:

So the checks had been deposited.

And — assuming she’d been honest, which he had to assume — then his weekly checks had covered the checks she wrote from the Prudent Company account to the various people she’d been working with. He did not know who these people were, but one or more of them might know what Prudence Ann Markham had done with the goddamn film . Was the negative still at a lab someplace? Which lab? Was she storing her work print in a safety deposit box at Calusa First? Or some other bank? Or at the bottom of a well? Where the hell was it?

He didn’t think it was in her house.

The police would have found it there, there would have been some mention in the newspapers or on television about a pornographic movie found in the home of the murdered lady film director. No, the film wasn’t in her house, and that wasn’t why he decided to break into it.

He decided to break into the house because her canceled checks, or her checkbooks, or her bank statements, or any or all of these might be somplace inside there.

He did not think the police would have confiscated anything that had to do with her financial matters. Why would they need such stuff? They already had her dumb husband.

But if the canceled checks, or her checkbooks, or her bank statements were inside that house...

And if he could find them...

Why then, baby, he would have names .

So at 11:45 that Saturday night, while the floral centerpieces were being auctioned at the Snowflake Ball, he drove out to 1143 Pompano Way.

Читать дальше