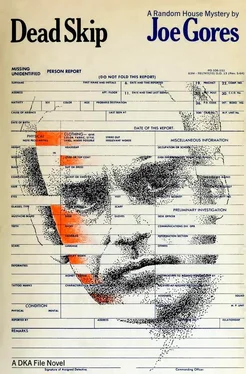

Джо Горес - Dead skip

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джо Горес - Dead skip» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1972, ISBN: 1972, Издательство: Random House, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Dead skip

- Автор:

- Издательство:Random House

- Жанр:

- Год:1972

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-394-48157-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Dead skip: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Dead skip»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dead skip — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Dead skip», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Joe Gores

Dead Skip

This one is for

Dave Kikkert,

who lives it every day,

and for

Tony Boucher and Fred Dannay

One

The 1969 Plymouth turned into Seventh Avenue from Fulton, away from Golden Gate Park. It was a quiet residential neighborhood in San Francisco’s Richmond District — white turning black, with a sprinkling of Chinese. The Plymouth went slowly; its brights picked out a couple of FOR SALE signs on narrow two- and three-story buildings. It was just midnight.

In midblock, the lone man behind the wheel saw a 1972 Mercury Montego hardtop parked directly across from the closed Safeway supermarket. He whistled thinly through his teeth. “Yeah, man,” he said softly, “squatting right on the address.”

He parked around the corner. From his clipboard he selected a sheet of paper with several pink report carbons stapled to the back of it, folded it into thirds, and slid it into his inside jacket pocket. From beneath the dash he unhinged a magnetic flashlight; from the glove box he took a hot wire, a ring of filed-down keys, and two oddly bent steel hooks.

The heavy rubber soles of his garage attendant’s shoes made no sound on the sidewalk. By the streetlights he was very black, with a wide flared nose and a thin mustache and an exaggerated breadth of shoulder which made him look much heavier than his 158 pounds.

The Montego was locked.

As he shone his flashlight through the window on the driver’s side, a head appeared behind the white lace curtain in the central bay window at 736. If the black man saw it, he gave no indication. The face disappeared abruptly; moments later the recessed front door opened to spill a bulky shadow out across the steps.

“Hey, you! Get to hell away from that car!”

When the other man did not comply, he came cautiously down the steps on stockinged feet. He had a round pale face and wavy brown receding hair.

The black finally looked at him. “Are you the owner of this car, sir?”

“Yeah, what the hell busi—”

“Are you Harold J. Willets?” he persisted. He had to refer to his sheet of paper for the name, even though it was not a new assignment. He thought in terms of autos and licenses and addresses, not names.

“Yeah,” said Willets again, edging closer to see the paper.

The black man nodded briskly, like a doctor whose diagnosis has just been confirmed by the x-rays. “Yes, sir. My name is Barton Heslip, I have a repossession order for your Mercury.”

“A repossession order? For my car?”

“A legal order from the bank, yes, sir. Could I have the keys, please?”

“No, you can’t have the keys, please,” mimicked Willets. He had gained confidence in talking. “And you can’t have the car. You go tell the bank you couldn’t find it. Wouldn’t have found it if the garage lock hadn’t been busted.”

Heslip was not surprised; he had broken off a toothpick in the lock earlier that evening, hoping that Willets would leave the car in the street when the garage key would not work. He had been trying to catch the car outside the garage for a week.

“What is it, Harry?” A woman had appeared at the head of the steps. She wore a faded pink terry-cloth robe and woolly slippers.

To Heslip, Willets said, “You can go to hell,” to his wife, “This ni... his guy says he’s from the bank, wants to take my car.”

“What?” Outrage shrilled in her voice. She pattered down the steps, hair in curlers and face cold-creamed. “He can’t do that. Harry, you tell him he can’t do that.” Heslip sighed: wives were a drag. She went on, seeing the repossession order in his hand, “You said the bank. Who’s this Daniel Kearny Associates?”

“We’re an investigation agency employed by the bank, ma’am.”

“We never got no notice or anything—”

“You’re three payments delinquent tomorrow,” he said patiently. “No bank would let an account get that far down without notification. Besides, you knew you hadn’t made the payments.”

“Well, you can’t have the car,” said Willets. “Mae took the payments into the bank just today.”

“Then you’ll have the cashier’s stamp in your payment book.”

Mae cast an angry glance at her husband. “I... mailed them in.”

“Then I’ll look at the check stub.”

“I... I sent cash,” she said desperately. “Just the cash money.”

“Uh-huh.” Heslip’s voice became suddenly, savagely scornful. “You just stuck a rubber band around three one-hundred dollar bills and threw them into the mailbox.” He turned to Willets. “Are there any personal possessions you’d like to remove from the car?”

Willets moved his stockinged feet around on the damp sidewalk as if belatedly realizing they were cold. It was a crisp spring night with just a touch of ocean wind and the vaguest hint of mist. “I lost the keys,” he said complacently.

Heslip shrugged. He took one of the steel hooks from his pocket, inserted it into the joint between the front and rear side windows, and gave a quick flick of a powerful wrist. The door was open.

“Hey, you black bastard!” yelped Willets, startled.

Heslip spun swiftly, skipping sideways to be free of the Montego’s door. His eyes were black coals. Willets backed off hastily from the look on his face, his hands up placatingly.

“Don’t you dare lay a hand on my husband!” Mae shrilled. “What kind of man are you, preying on decent folks—”

“I pay my bills,” said Heslip. He was breathing harshly.

The white man’s mouth was working. “Oh, to hell with you,” he said suddenly. “Take the goddamn thing!” He jerked a bunch of keys from his pocket and threw them with all his might at the Mercury. They starred the driver’s window with multiple fine fracture lines.

Heslip picked them up from the gutter. “What about your possessions?” His voice was even once more.

“That’s your lookout — and they all better be there when I get that car back, or I’ll sue your dead-beat company...”

His voice trailed off as he stamped up the brick-edged stairs. His wife followed, her back rigid with contempt and indignation. At the head of the stairs, with the front door open, Willets turned back. “Just what you’d expect from a nigger!” he yelled. Then he was inside behind Mae, slamming the door.

Heslip got into the Mercury, sat with his hands rigid on the wheel like a man in catalepsy. Finally the tension began leaving his features; he shrugged; he even grinned. “No class, baby,” he said aloud.

It took only four minutes to park around the corner behind his company Plymouth and fasten his tow bar to the Mercury’s front bumper. He left on the parking lights. Before starting off with his tow, he wrote the date and a few scrawled notes to himself on the face of the uppermost pink report carbon. These would form the raw data, later, for his typed report on the Willets assignment.

At Arguello, he unclipped his radio mike from the dash. “SF-3 calling SF-6. Do you read me, Larry?”

No response. At USF he took the linked cars over to Golden Gate, one-way inbound to the office, and tried again. This time he was successful. “How you doing, man?” he asked.

“Not a thing.” The disgust in Larry Ballard’s voice came through the mike clearly. “Haven’t seen a car. You’re having a good night.”

Which meant Ballard had been by the office, had seen the two repos Heslip already had brought in.

“Got that Willets Merc on the tow bar right now.”

“That toothpick in the lock actually work?”

“Like a charm, man. Willets don’t like culluhed folks, but he gave me the keys. Where you at now?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Dead skip»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Dead skip» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Dead skip» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.