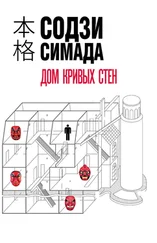

Kozaburo Hamamoto, along with Michio and Hatsue Kanai, Kumi Aikura and Sasaki took the west stairs up to the door of the Tengu Room. As she had done the previous time, Kumi looked in through the window, the only one in the house that overlooked an interior corridor rather than the exterior. It was a huge window, giving a view of the whole room.

The window stretched all the way from the south wall corner to about 1.5 metres shy of the doorway, a total width of about 2 metres. It could be slid open about 30 centimetres from either the left or right side, leaving either or both sides open. That’s how all the glass doors of the cabinets in this room were usually slid open too.

Kozaburo got out a key and opened the door, revealing that no matter how much of an impression you could get of the room by viewing it through the window, it wasn’t until you stood inside that you could really take in the spectacle. First of all, right by the doorway stood a life-sized clown. It had a cheerful smiling face, but a rather depressing, musty smell.

There were all kinds of other dolls in the room, both large and small, all a little threadbare. They had aged, and looked almost on the point of death, but their youthful expressions were still intact. Their grimy faces with their peeling paint seemed to Kumi to be concealing some kind of vague madness. Either standing or sprawling in a chair, each one smiled faintly with some kind of unfathomable emotion. They were suspiciously quiet, looking like something you’d see in the waiting room of a psychiatric hospital in your worst nightmare.

As if their flesh had gradually been stripped away over time, the paint of their faces had peeled and scabbed over, exposing a little of the craziness inside. The part that had decayed the most were the smiles on their red, peeling lips. By now they didn’t even seem to be smiling any longer—these dolls had the most enigmatic look of pure evil. Their smiles had the power to send an instant chill through anyone who looked at them. Decomposition—that was the perfect word for it. The smile that had been on the faces of these cherished dolls had transmuted, decomposed. There was no better way of putting it.

A deep-seated grudge. They’d been brought into the world by the whimsy of human beings, but then not permitted to die for a thousand years. If the same thing were inflicted on our bodies, the same look of madness would appear on our faces too. Ever in search of revenge, our madness would grow in intensity, fed by the grudge we harboured.

Kumi let out a small but genuine scream. However, it was nothing compared to the residents of this room whose mouths were permanently poised on the edge of a scream.

The south and east walls were completely red with Tengu masks, with their huge long noses and fiery eyes that glowered at the room’s doll occupants. It seemed to the guests that the Tengus’ job was to stifle the screams of the dolls.

Hearing Kumi scream seemed to put Kozaburo in a cheerful mood.

“Well, this place is as amazing as ever,” said Michio Kanai, and Hatsue nodded with great enthusiasm. But this kind of small talk felt out of place in the heavy atmosphere of the room.

“I’ve always wanted to set up a museum, but I was always so busy with work. In the end, this display room is all I was ever able to put together.”

“It’s already a museum,” said Kanai.

Kozaburo gave a little laugh.

“Well, this is, anyway.”

He opened one of the glass cases and took out a small figurine, about fifty centimetres tall, of a boy sitting in a chair. The chair had a little desk attached to it, and the boy had a pen in his right hand; his left rested on the desk. He had a sweet expression on his face, and this figurine lacked the visible wear and tear of the other dolls.

“He’s so cute!” said Kumi.

“It’s a clockwork doll, or automaton, known as The Writer. It was made in the late eighteenth century. I heard about it and went to great pains to get hold of it.”

The assembled guests made various admiring sounds.

“Did it get its name because it can actually write words?” asked Kumi, sounding a little scared.

“Of course. I think it can still manage to write its own name. Would you like to see?”

Before Kumi had a chance to respond, Kozaburo tore off a sheet from a memo pad and slipped it under the doll’s left hand. Winding the spring in the doll’s back, he gave its right hand a gentle nudge. The doll’s right hand began to make awkward, jerky movements which started to leave marks on the memo paper. There was a small clacking sound that must have been the grinding of the cogs inside.

Kumi was relieved to find the movements delightful rather than menacing. Even the occasional change in pressure of the doll’s left hand on the paper was charmingly realistic.

“That’s adorable! But at the same time a little bit scary.”

Truth be told, everyone present was feeling slightly relieved. No one had been sure what to expect.

The doll was only able to write a tiny bit. It came to an abrupt halt with both hands just above the desk. Kozaburo removed the paper and showed it to Kumi.

“Well, it’s over two hundred years old, so it’s not surprising it’s not as good as it used to be. Can you make out the letters M, A, R, K? This boy’s name is Marko so he almost got his full name down.”

“Signing autographs, just like a celebrity!” said Kumi.

“Yeah, I’m sure there’ve been plenty of celebrities who couldn’t write more than their own name,” said Kozaburo with a grin. “Apparently he used to be able to write much more, but this is his whole repertoire now. I guess he must have forgotten his alphabet.”

“His eyesight’s probably failing with age, if he’s really two hundred years old.”

“That’s a good one,” said Kozaburo. “Maybe I’m the same way. But at least I’ve given him a ballpoint pen to use. The pen he used to have was much harder to write with.”

“How wonderful! If you don’t mind my asking, is it worth a lot of money?” said Hatsue.

“I don’t think you can put a price on it. It’s something that could easily belong in the British Museum. If you’re asking me how much I paid for it, I’m afraid I can’t answer that. I wouldn’t like to shock you with my total lack of common sense.”

“Ah!” said her husband.

“But if we’re talking money, this piece here was even more expensive. This is The Dulcimer Player.”

“Did it come with that desk?”

“It did. The mechanics are hidden inside.”

The Dulcimer Player was a noblewoman in a dress with a long skirt, seated in front of what looked like a miniature grand piano. Both were attached to the top of a beautiful mahogany desk. The doll itself wasn’t particularly large, probably no more than about thirty centimetres.

Kozaburo must have operated some sort of hidden device, because all of a sudden the noblewoman’s hands began to move and music filled the room.

“She’s not really playing, is she?” said Sasaki.

“No. That would be too complicated to design. I suppose you could think of this as a very elaborate music box. A music box with a doll attached. It’s the same principle.”

“But the music isn’t that tinkling sound you get with a music box,” Sasaki pointed out. “It’s much more rounded and mellow than that—there’re not only high notes but low ones too.”

“Yes, it sounds more like bells to me,” said Kumi.

“Probably because the box itself is so large. And unlike the little boy, Marko, she has quite a wide repertoire. About the number of tunes on one side of a long-playing record.”

“Really?”

“Yes, it’s a masterpiece from the French rococo period. And this one here is German-made from the fifteenth century. It’s called Clock with Nativity Scene.”

Читать дальше