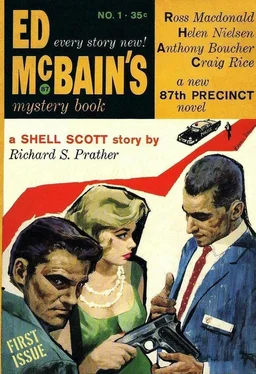

Anthony Boucher - Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Anthony Boucher - Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1960, Издательство: Pocket Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pocket Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1960

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Possibly more serious was Joan’s jealousy. Sangret owed a thank-you letter to the woman in Halifax who sent him blades and perfume. With a spectacular absence of tact he asked Joan to write the letter for him. Joan did so, but she was still brooding about it the next morning. “You can’t love two,” she said, and was not mollified by Sangret’s explanation that Mrs. Oak was “more of a friend.”

That was Monday morning, September 14 — the last time, according to his statement, that Sangret ever saw Joan alive.

On October 8, the day after the finding of the body, Chief Inspector Edward Greeno of New Scotland Yard came down to Surrey.

Molly Lefebure, whose employer, Dr. Simpson, worked frequently with Greeno, has described him on an earlier case in 1941:

“More than anything else he resembled a huge, steel-plated battle cruiser, with his jaw thrust forward instead of a prow. He spoke little, noticing everything, and was tough, not in the Hollywood style, but genuinely, naturally, quietly, appallingly so.

“I found myself misquoting Hilaire Belloc on the subject of the Lion — but it did just as well for Mr. Greeno: ‘His eyes they are bright/ And his jaw it is grim,/ And a wise little child/ Will not play with him.’

“... He started asking questions in a rather rasping voice that sent shivers down my spine. He was on the warpath, and I thought, ‘God help the poor fool he’s after.’ ”

For most of a week, from Monday, October 12, through Friday, October 16, that rasping voice questioned August Sangret. Even at the cost of damaging the novel reader’s illusion as to the meticulous chivalry of Scotland Yard, it must be pointed out (because Greeno reluctantly admitted it in cross-examination) that he never, at any point, issued the customary may-be-used-against-you-in-evidence caution, nor did he invite any superior officer to attend this questioning of an illiterate private.

Sangret held up astonishingly well under this treatment. He told and retold the story from which I have often quoted, and insisted that so far as he knew Joan had simply disappeared on September 14. No, he had not made any strenuous effort to find her. (How could he?) Yes, he had made several contradictory remarks to friends who asked, “Where’s Joan?” (Who is humble enough to say simply: “She walked out on me”?)

Much has been made of the fact that Sangret seemed aware of Joan’s death before he was officially informed. Prosecutor Neve, for instance: “But when he had finished making that statement, he said this: ‘I guess you have found her. Everything points to me. I guess I shall get the blame.’ You may ask yourselves why he should say that, if he did not in fact know that she was at that moment lying dead, and also know how her death had come about.”

You may also ask yourselves just what you would think if a Scotland Yard bigshot grilled you all week on your relations with a missing girl, and asked you to identify, piece by piece, the only clothes you had ever seen her wear.

When the statement was completed (one of the longest statements ever taken from a defendant in England), Greeno realized that the Indian had proved a match for the Inspector on the warpath. He went back to London without recommending an arrest.

Then, more than six weeks later, on November 7, Lance-Corporal Albert Godfrey Gero, Cape Breton Highlanders, was detailed to clean out a stopped-up drain in the washhouse at the Witley camp. The stoppage had been caused by waste paper accumulated around a knife.

The knife was identified as Sangret’s, despite his denial. It was not general issue, but a type unfamiliar to the Canadian Army and easily remembered by witnesses. Sangret had visited that washhouse on October 12, just before Greeno began his interrogation. And the knife had a peculiar hooked tip precisely compatible with the curious wounds observed by Drs. Simpson and Gardner.

Just to confuse the issue, there had, at some point, been another knife — which brings us to the singular episode of Sergeant James Henry Smith, Surrey Constabulary, Dorking.

During the death struggle Joan’s handbag and its contents had been widely scattered. After the body had been discovered, the police searched the area thoroughly, and their finds helped to establish the identity of the victim.

Sergeant Smith knew that he was hunting for anything connected with a murdered woman. He found a handbag and tossed it aside. “I thought it was nothing to do with the job.” (Fortunately another officer picked it up; it was indeed Joan’s.) Near the same spot he found a knife and threw it away. “I did not think it had anything to do with it at all.”

Two weeks later he thought to mention this fact to his superiors; a second search found nothing.

The Smith knife was, if one can believe so moronic a witness, “similar to that [the washroom knife] but in worse condition... very rusty.”

It was undoubtedly the knife that convicted August Sangret. Attempts to establish the presence of bloodstains on his battle dress and blankets were inconclusive. Without the knife the prosecution case amounted to little more than “Well, who else?” (not that this argument is without effect on jurors); and there was plausibility to the defense contention that any passing soldier might have hopefully misinterpreted Joan’s amiability (like Private Deadman) and become inflamed to the point of attempting rape. But the knife is hard to get around.

If Sangret killed Joan, why did he do so? The prosecution (under no obligation to prove motive as part of its case) alternatively suggested a jealous rage or a desire to disencumber himself of a pregnant woman insistent upon marriage. The former seems better suited to the nature of the crime.

A third possibility would seem to be the realization that “his” unborn child was actually that of Francis or even of some previous soldier. Or possibly a quarrel arising from the discovery that she was not pregnant at all. (She had missed her period in July and August; the September period would have been due the weekend of her death.)

But murderers have no more need than prosecutors for a precisely defined motive. Life and intimacy and tensions...

In Leipzig, in 1821, a soldier-barber named Johann Christian Woyzeck was tried for murder, and upon his crime Georg Buchner (1813–1837) based the superb psychological drama Woyzeck — a work almost a century ahead of its time. From this play Alban Berg (1885–1935) adapted his atonal opera Wozzeck (1925), one of the most significant and influential works for the modem musical stage.

Play and opera tell the story of an ignorant and confused soldier who loves a girl named Marie and gets her pregnant. Marie is a girl of simple charm, with moments of remorse and depression and longing for death, but generally happy, whether reading her Bible or flirting with passing soldiers. The jealous Woyzeck stabs her, and later drowns himself accidentally in a frantic search for the weapon because “that knife will betray me.”

Both works express infinite compassion for tormented people in an incomprehensible world.

The real-life Woyzeck was unquestionably paranoid (though sentenced to death). August Sangret was un-arguably sane. The fair trial lasted from February 4 to March 2, 1943; and on March 2, after two hours of deliberation, the jury brought in the verdict: “Guilty, but with a strong recommendation to mercy.”

Previous commentators have expressed surprise at that rider.

Sangret appealed the verdict, apparently on his own. Defense counsel (Linton Thorp, K.C) flatly told the Court of Criminal Appeal that he could see no ground on which the verdict could be disturbed. The Court agreed: no point of law arose, and the adequacy of the evidence was within the exclusive province of the trial jury.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, No. 1, 1960» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.