I don’t want to die, he thought. I haven’t lived yet

It seemed very important to him that he take off the purple jacket. He was very close to dying, and when they found him, he did not want them to say, “Oh, it’s a Royal.” With great effort, he rolled over onto his back. He felt the pain tearing at his stomach when he moved, a pain he did not think was possible. But he wanted to take off the jacket. If he never did another thing, he wanted to take off the jacket. The jacket had only one meaning now, and that was a very simple meaning.

If he had not been wearing the jacket, he would not have been stabbed. The knife had not been plunged in hatred of Andy. The knife hated only the purple jacket. The jacket was a stupid meaningless thing that was robbing him of his life. He wanted the jacket off his back. With an enormous loathing, he wanted the jacket off his back.

He lay struggling with the shiny wet material. His arms were heavy, and pain ripped fire across his body whenever he moved. But he squirmed and fought and twisted until one arm was free and then the other, and then he rolled away from the jacket and lay quite still, breathing heavily, listening to the sound of his breathing and the sound of the rain and thinking, Rain is sweet, I’m Andy.

She found him in the alleyway a minute past midnight. She left the dance to look for him, and when she found him she knelt beside him and said, “Andy, it’s me, Laura.”

He did not answer her. She backed away from him, tears springing into her eyes, and then she ran from the alley hysterically and did not stop running until she found the cop.

And now, standing with the cop, she looked down at him, and the cop rose and said, “He’s dead,” and all the crying was out of her now. She stood in the rain and said nothing, looking at the dead boy on the pavement, and looking at the purple jacket that rested a foot away from his body.

The cop picked up the jacket and turned it over in his hands.

“A Royal, huh?” he said.

The rain seemed to beat more steadily now, more fiercely.

She looked at the cop and, very quietly, she said, “His name is Andy.”

The cop slung the jacket over his arm. He took out his black pad, and he flipped it open to a blank page.

“A Royal,” he said.

Then he began writing.

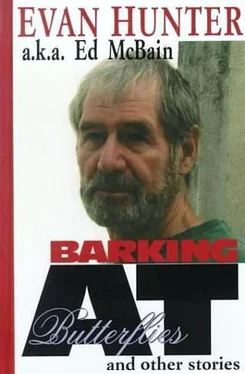

Trying to pin down the stories in this collection is like trying to take a snapshot of a pit of vipers. Of the eleven stories in the book, only two of them were originally published under the Ed McBain pseudonym. “The Intruder” first appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in 1970. Barking at Butterflies, from which the collection takes its title, was first published in 1999. In fact, before May of 1956, when the first 87th Precinct novel was published, Ed McBain didn’t exist.

You may wonder why there was a need for Ed McBain at all. By 1956, Evan Hunter was already a bestselling novelist. So why Ed McBain? Here’s why. My publishers felt that if it became known that Evan Hunter was writing mystery novels, it would be damaging to my career as a “serious novelist,” whatever that may be. I personally consider writing mysteries as serious an occupation as writing any other kind of fiction. But these were older, wiser men (I was not yet thirty at the time) and so I followed their advice. Besides they had given me a contract for only three books, and I never once suspected the series — with its renegade concept of a conglomerate cop hero in a mythical city — would ever capture the public imagination. The irony, of course, is that Ed McBain may now be better known around the world than Evan Hunter is.

Nine of the stories in this volume were published under my own name. Three of them have never before been published in the United States. Most beginning writers think that once a writer is published — and The Blackboard Jungle was an enormous success, mind you — the rest is sliding on ic e send a new story to a magazine, it’s automatically purchased and a check for $10,000 arrives in the mail the very next day. Sure. But no editor in the United States thought “Short Short Story” or “Motel” were good enough to publish in any magazine. (The most recent American rejection on “Motel” was in 1999.) Before now, “Short Short Story” was published only in Australia and Germany in 1978. “Motel’s” first (and on appearance was in the German edition of Playboy in 1978. “The Movie Star” was never published here, either. It first appeared in a British anthology in 1996, and has since been published in Holland and South Africa.

Of the published Evan Hunter stories in this volume (my publishing life hasn’t been entirely one of rejection, abandonment and loss) “Uncle Jimbo’s Marbles” first appeared in Redbook in 1963, “First Offense” in Manhunt in 1955, “On the Sidewalk, Bleeding” in that same magazine in 1957, “The Beheading” in a now defunct Playboy imitator called Escapade in 1965, and “The Birthday Party” in Playboy itself in 1967. Perhaps the short story that accounts for Evan Hunter still being here at all is “To Break the Wall.” It first saw the light of day in an experimental magazine called Discovery, published in paperback format by Pocket Books, Inc. in 1953. You may recognize it as the penultimate chapter of The Blackboard Jungle.

Evan Hunter a.k.a. Ed McBain

Weston. CT