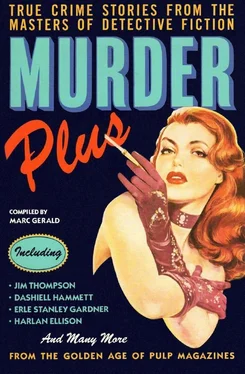

Харлан Эллисон - Murder Plus - True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Харлан Эллисон - Murder Plus - True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Pharos Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pharos Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-88687-662-3

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He asked his questions in a dry, patient voice that seemed interested in eliciting facts and nothing else. He kept jotting down the endless information in a small notebook with a torn cover.

The dapper man said that he was an air-raid warden, that his name was Arthur Kraus and that he was married and lived at 298 West 86th Street.

“Know Clyde Warner’s address?” asked Cassidy.

“No, but you can look it up. In the file box.” Kraus approached the table and halted suddenly. “That’s funny,” he said.

“What?”

“The file box. The cards with the names and addresses of all the wardens. It’s always there, on the table.”

“Maybe it’s in the next room. What did it look like?”

“A cardboard box, mottled like marble. It was about sixteen inches long and five inches wide. We used four-by-five filing cards. The box has to be there.”

Cassidy turned to one of the precinct patrolmen. “See if you can find it, Jim.” He stared thoughtfully at Kraus. “All right — go ahead.”

The warden explained that sector headquarters, under the reorganization which had taken place a few months previously, had to be manned twenty-four hours a day. The men divided up the night work. Some of them took two four-hour shifts a week; others, like Warner, preferred to put in a single eight-hour stretch and get it over with. At 8 A.M. they went off duty, in time to freshen up and reach their offices on schedule. Since the women who manned headquarters during the day didn’t report until nine, there was a gap of one hour. Kraus, being his own boss, filled in three times a week. If he was late getting to his office, it didn’t matter.

Cassidy frowned. Kraus was full of meaningless details, but the detective didn’t stop him. There might be something of importance, something unusual. Like the missing file box.

The patrolman returned and reported that he couldn’t find it. There were no places in the sparsely furnished apartment where a file box could get lost or be hidden. Why wasn’t it there? Who’d want to take a thing like that? What for?

Kraus kept talking. He liked to report a few minutes ahead of time. It meant nothing to him, but the men who were on duty all night were tired and—

Cassidy interrupted. “Men?”

“Yes. There are always two, except when I’m here from eight to nine.”

“Who was on with Warner?”

Kraus picked up the big black book. There were blanks for names and hours of duty. He pointed to the last item.

“Clyde Warner, David Schirmer. 12:01 A.M. till—” No further entry had been made.

Here was something at last. Two men had signed in at midnight. In the morning only one of them was there, and he was dead.

“Where does Schirmer live?” asked Cassidy.

Kraus shrugged. “His address is in that file box,” he said. “Listen — it must be here.”

Cassidy walked over to one of the charts. On it, he read, “Sector Commander, Herbert Streit, 267 West 87th Street. Trafalgar 7-0800.” The Sector Commander — he might know.

He instructed a patrolman to call Streit from outside. Nobody must touch the phone here. There might be fingerprints.

The next hour or so must have been a nightmare for Cassidy. The Headquarters staff arrived, the Medical Examiner arrived, the inspector of the division, the acting captains of the district and of the detective division arrived. The experts snapped pictures, dusted for fingerprints, examined the corpse. And meantime the Sector Commander and the Zone Commander of the Air Raid Service showed David Schirmer, the missing warden, lived in a furnished room at 323 West 88th Street.

Cassidy transferred himself to the meeting room with the long wooden bench. He asked his questions methodically. The brass hats interrupted and he had to bring all of them up to date, but he kept doggedly to his line of inquiry.

Herbert Streit, the Sector Commander, was a tall, serious man with thin shoulders and a tired face.

“I’m Streit,” he drawled. “Of Streit and Galbraith, Advertising.”

“So? What do you know about these two men? David Schirmer, Clyde Warner.”

Streit sat down. He was too tall to be comfortable in the folding chair and he kept wrestling with it, twisting his long legs around it and sliding gradually toward the edge.

Schirmer, he stated, was waiting for his induction notice and had volunteered to take charge of headquarters whenever necessary. He was on twice a week. Streit hadn’t met him until a few months before, when the air-raid service had started to function, but he had found him exceptionally likable.

Streit shifted to Clyde Warner. The latter was without question the most disliked man in the organization. He was bossy and aggressive and had threatened to resign unless he was made a squad leader. As a jewelry salesman, he was accustomed to carrying valuable merchandise. For that reason he had a pistol permit. When he reported for duty, he always placed his gun ostentatiously on the table, as if he were the real stuff and everyone else an amateur. His manner had made him many enemies. Streit was one of them.

He hesitated, as if he were not sure whether it was wise to proceed. Then, after a short pause, he hooked his leg through the chair rung and went on with his story.

Headquarters had been furnished almost entirely by the wardens and their families, he explained, and it was they who had contributed money for office supplies, phone service and other basic essentials. Despite a specific order to the effect that the Air Warden Service had no right to collect funds, Streit had written to a few residents in the sector suggesting that donations would not be amiss. Warner had heard of this and reported it to the Mayor, who had demanded Streit’s resignation. He had tendered it yesterday. The incident had caused considerable ill-feeling.

“You mean you had an argument with Warner?”

Streit smiled for the first time. “I was more inclined to thank him. The headaches I’ve had over this, the responsibility and the demands on my time and purse — they’re over at last. Do you know that I haven’t had a free evening since the war started?”

It sounded plausible and Cassidy made no comment. He picked up the log book and read off the names of the two men who had been on the eight-to-twelve shift.

“They’d know who came on at midnight,” he said. “See if you can locate them and get them here, without telling them why.”

Streit nodded and, with an expression of relief, got up and went toward the phone. Cassidy headed for the back of the room to examine the small pile of objects taken from the dead man’s pockets.

Besides the pistol permit, there was only one thing of interest — a printed form, reading, “In case of accident, please notify—” The blank had been filled in with the name of Mrs. Clyde Warner, 50 West 79th Street, and then crossed out and the name of Harold Warner, 286 West 89th Street, substituted for it. The 89th Street house was Clyde’s address, too. Cassidy ordered Detective Francis Hanrahan to go there and hold Warner until questioned. Then he addressed the Medical Examiner.

“When was he killed?” he asked.

The Medical Examiner shrugged. “You guys always expect magic. I’d say around two or three in the morning. That’s a guess. I’ll check on it later and let you know.”

Cassidy swung around. “What about prints?”

A discouraged little man who was working with fingerprint powder and a brush looked up. “Either we don’t find any at all or we find too many,” he said glumly. “This time it’s too many. There’ve been a lot of people in and out of this place.”

“What about that whiskey bottle and glass?”

“Half dozen nice clear prints. But they all match up with the guy who was shot.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Murder Plus: True Crime Stories From The Masters Of Detective Fiction» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.