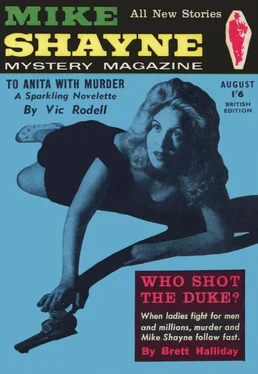

Jay Carroll - Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jay Carroll - Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition)» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Sydney (London), Год выпуска: 1957, Издательство: Frew Publications (distributed by Atlas Publishing & Distributing), Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition)

- Автор:

- Издательство:Frew Publications (distributed by Atlas Publishing & Distributing)

- Жанр:

- Год:1957

- Город:Sydney (London)

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition) — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But a hole that deep takes a lot of filling up. Even sales like that couldn’t do it, and I won’t tell you how much I still owe. To make it worse, now that I have one big property, my creditors, people who for years just let things slide along, now suddenly want to take over. I can’t let them, Ellie — not now, not at my age, not with real freedom, real solvency, right in my grasp for the very last time. All I need is one more big seller, and you’ve got it there for me, and you won’t let me have it. Ellie, I beg you, on my knees I beg you, finish the book!

Brill.I hate pink, thought deMarcopolo with sudden fury. He controlled the hand which wanted to crush the pink sheet and read—

I have said all I can say. I enclose a copy of it. Read it again.

E.A telegram — its porous yellow startled him like an explosion.

ONLY TEN DAYS TO CONTRACT TIME FOR HEAVEN’S SAKES ELLIE AT LEAST LET ME SEE YOU.

BRILL MacIVER.And then, the shortest pink carbon of all—

Read it again.

E.DeMarcopolo picked up the next one, Office of the Publisher, squinted at it, then set the box down on the floor and stood up. He moved to the window, leaned into the light and spelled out the writing slowly, his lips moving. It was scratched and scrawled, the paper crumpled, speckled with ink-flecks where the pen had dug in and splattered.

I must be crazy, and I wouldn’t wonder. Nothing seems real — you, soft little you, holding out like that for such a thing, I listening to it. No money, no business in the world, is worth a thing like this, I keep telling myself, but I know I’m going to do it. Try

Down at the bottom of the memo sheet was a wavery series of scrawls which at first seemed like the marks one might make to try out a new pen — a letter or two, a series of loops and zigzags. But as he stared at it, it became writing. As nearly as he could make it out, it read—

I did, and he didn’t know why. My blood damns you, Ellie.

Lance deMarcopolo turned like a sleepwalker and slowly put the crumpled memo down on the pile of papers he had already gone through. He stood still, swaying slightly, then moved unsteadily toward the corner where the telephone squatted on the floor, like a damsel in a hoopskirt. He picked it up, held the receiver to his ear. It was still connected. He dialled carefully.

A cheerful female voice said, “Post-Herald.”

“Get me Joe Birns... Joe? Lance here.”

“Hi, y’old bibliophile! Don’t tell me you’re gettin’ cold feet, old man. Call the whole thing off and give your old pal a scoop.”

“Knock it off, Joe.”

“Hey! ’Sa matter, Lance?”

“Joe, you can find things out without anybody knowing who’s asking.”

“Shucks, Lance, sure. What’s—”

“Brill — MacIver Brill — I want to know what happened to him.”

“Brill? He’s dead.”

“I know, I know.” It seemed, somehow, hard to breathe. “I mean, I want to know how he died. And somebody else, too — hold on.” He put the ’phone down on the floor and walked back to the box. He pawed through the papers for a moment, then returned to the ’phone. “Joe?”

“Yuh?”

“Somebody called Hobart Hennigar. I think he’s dead, too.”

“Hobart Hennigar,” murmured Joe like a man taking notes. “Who dat?”

“That’s what I want to know. Call me back, will you, Joe — fast?” He read the number off the telephone.

“Sure, Lance. Hey, Lance, are you — is there anything...?”

“Yes. Joe — find me that information.” Lance hung up.

He looked vaguely about the room, everywhere but at the box. Yet, ultimately, he went back to it, inevitably drawn. Slowly, he sat down and picked it up, still not looking at it. His hands found the unread portion and slid over it like a blind man’s. At last he lowered his eyes and looked.

It was only manuscript:

... and threw on the gold hostess gown. When the old man opened the door she stood like a flame, eyes like coals, hair afire in the golden morning. “Maserac. Maserac, he’s killed me!”

And she told him, told him all of it, each syllable tom from her, agonised yet strangely eager, for each syllable brought her closer to the comfort she knew that her dear friend would somehow have for her. And, when at last she had finished, she ran to him, blind with tears, and hid in his arms.

“My dear, my poor little bird,” said Maserac. His arms closed around her. “Try to forget, Furilla. To-night — tomorrow — this will be a world in which Harald does not exist.” He put her firmly from him, looked for a long time into her eyes, then slowly turned to the door.

“Maserac, Maserac, what are you going to do?”

“Do?” He smiled gently. “Surely there is only one thing to do. How could there be a choice?”

He left her.

In the morning, they found Harold’s tattered body slumped in his cabin. And Maserac, dear Maserac — his fury had crushed, not only Harald, but his own great heart, his dear, dear heart. He lay in an open field, his slack hand still on the horsewhip, his unseeing eyes turned to the sunrise, and Furilla knew that her name lay silent on his dead lips.

“Yeah,” whispered deMarcopolo. The sound was like sighing. “That was the way the thing came out in the book.”

Everything came out for Furilla. All the world loved Furilla, because things always happened the way they should for Furilla.

“Yeah,” he said again, still in a whisper.

Furilla, he reflected, never did anything to make things come her way. She did it just by being soft little, sweet little, innocent little Furilla — being Furilla beyond all flexibility, beyond all belief.

The ’phone rang.

“Yes, Joe.”

Joe said, “I don’t know just what details you want about Brill. There’s a good deal that wasn’t in the papers, though. He went on a wing-ding and disappeared for two days. They shovelled him up out of a doorway down in the waterfront district. He was full of white lightning, but whether that killed him or his pump was due to quit, anyhow, is a toss-up. That what you wanted?”

“Close. What about the other one?”

“Took a little digging. Now Hennigar — Hobart Hennigar, thirty-seven, instructor in English Lit., and creative writing at some Eastern college, thrown out three years ago for making a pass at a housemaid. Fast talker, good-looker, fairly harmless. One of these literate bums. Knocked around, one job to another, wound up out at the lake, caretaker on a big estate. Ties in with MacIver, in a way, Lance — MacIver had a place out there, too, little lodge. Used to hole up there once in a while.”

“Was he out there during his drunk?”

“If he was, no one could prove it. Off season, pretty lonesome out there. Anyway, this Hennigar got himself plugged through the head. Police report says it was a twenty-five target-type bullet.”

“Fight?”

“No! Back of the head, from a window in his cabin. He never knew what hit him, not a clue. Lance—”

“Mm?”

“You got a lead on that killing?”

DeMarcopolo looked slowly around the room. The telephone said, “Lance?” and he held it away from him and looked at it as if he had never seen it before.

Then he brought it back and said, “No, I haven’t got a lead on that killing. Joe, do something for me?”

“Shucks.”

“You covering that thing of mine?”

“Statement at the airport, kissin’ picture? Couldn’t keep me away.”

“I... won’t be there,” said deMarcopolo. “Tell her for me, will you?”

“Lance! What’s hap—”

“Thanks, Joe. ’Bye.” He hung up very quietly.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, August 1957 (British Edition)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.