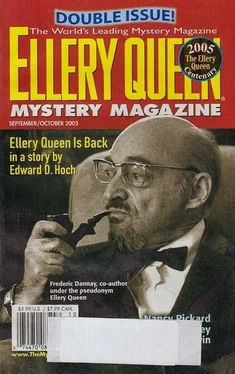

Тимоти Уилльямз - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Тимоти Уилльямз - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Dell Magazines, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Magazines

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Harriet was indeed a regular worshiper at the Ebenezer Chapel in Trafalgar Street, where the rigorous and belligerent tone of the services matched her own martial spirit. She was no Sunday Christian, but brought her values into every corner of everyday life. She had a withering glance that could have felled a bay tree, and she used it against young people holding hands, sometimes followed by “Shame on you” or some variant of it. Children playing ball in the street were sent scurrying for cover by her shrill objections, and any woman whose clothes were visibly dirty would be assailed by words such as “slattern” or “slut.” Cleanliness and teetotalism were up there beside godliness in her scale of values: Boys emerging from the Gentleman’s conveniences in Trafalgar Street would be asked to show her that they’d washed their hands, and the smell of beer on the breath of a passing labourer would elicit the outraged cry of “Drunken beast!”

“Give it a rest, old woman,” said one of her victims. “Just because your tipple is vinegar doesn’t mean the rest of us can’t enjoy a pint or two of summat nicer.”

But the object of her particular wrath in the months before her death was the house on the corner of Trafalgar Street and Gladstone Road, one whose entrance she could see from all the front windows of her own house. After the death of Mr. Wisbeach, the house had been sold (his son lived in Wimbledon, and had no conscience about what happened to the neighbourhood he grew up in). It soon became clear to Harriet Blackstone that the new owners were unusual. There were several women apparently living there, but no man. To be precise, the house contained no man, but from time to time it did contain men. Several members of the frail sex came and went, often regularly, but none of them lived there. Harriet soon began to suspect that some of the women were also only there on an occasional basis. The explanation for this irregularity eventually occurred to her.

“The place is no less than a brothel!” she said to the Ebenezer’s minister.

“I should prefer the phrase ‘House of Pleasure,’ ” he said. There was no inconsistency in his rebuke. “Pleasure” was always, for him, a dirty word.

Steady and prolonged observation of the house only strengthened Harriet’s conviction. One fine afternoon she marched around to the Walthamstow police station and demanded to see the inspector in charge, refusing to say what she wanted to talk to him about. Such was her force of personality that she got her way, though normally the constable on the duty desk would have shielded his boss from the force of any public indignation.

Inspector Cochrane took his feet off the desk (he wore size thirteen boots, which had for a long time hindered his promotion, as being more suitable for a walker of the beat rather than one undertaking a more thoughtful role, but eventually merit had won out). He welcomed Mrs. Blackstone and heard through her detailed account of the occupants of number three, Gladstone Road, and the male visitors that had been seen going there. He took no action to cut her short, merely lighting a cigarette and enduring the vicious glances she cast at it. When at last she drew to a close, he tipped the ash off the end of it and got a word in himself.

“Right,” he began. “Now, it may surprise you to know that you’re not the first to come to us over this little matter. I feel people might have done better to talk to the inhabitants of number three, so they got their facts right first, but new residents always take time to be accepted, don’t they? Anyway, we’ve made enquiries, and the family who bought the house from Mr. Wisbeach are called O’Hare. Their grandfather came over from Ireland to work on the Manchester to Leeds railway, and their father came south to work on building the station at Liverpool Street and on the lines going out from it. He died last year. It’s a big family, and the men in it are either married or working here and there around the country.”

“One of the regular visitors bears a distinct resemblance to the constable who directs the traffic at one end of Walthamstow High Street,” said Harriet waspishly.

“PC O’Hare. Quite,” said Inspector Cochrane. “Some of the men of the family visit regularly, some less often if they live further away — just as you’d expect. The mother, widow of the man who worked on Liverpool Street station, is not too badly off, and one of the daughters works for a dressmaker in Clerkenwell. I’m not sure I should be telling you their business, but I feel I should save time. So there you are. Problem solved.”

Harriet Blackstone, after a few moments’ meditation, cast him one of her bay-tree-withering looks.

“You’re telling me I’ve been wasting your time,” she said.

“I’ve said nothing of the sort.”

“Well, let’s wait and see: It’s Time as will tell,” she said, and she marched out of his office and the police station without so much as a goodbye.

As ill luck would have it, it was later that afternoon, when Harriet was still in a foul mood, that Charlie Paxman made his first visit to his new mother-in-law’s home. He had seen Sylvia going in when he was arriving back early from a job, and he had knocked at the front door to tell her he was off to the Wolf and Whistle for a pint.

“Bring him in. Let’s have a look at him!” shouted Harriet in the kitchen to her daughter at the front door. Charlie went through sheepishly and she surveyed his white-spattered and overalled form from top to toe.

“Well, you’re never going to set the Thames on fire,” she said.

“Such was never my hambition,” said Charlie genially. “And I doubt if Mr. Gladstone ’imself could ’ave achieved it.”

Mrs. Blackstone continued sharpening her carving knife on her whetstone, her way of relieving her frustration, and continued the attack. “Don’t you take the name of that godly man in vain,” she said (never having heard of the great man’s determined work among the fallen women of the Westminster area). “He was worth a hundred of you. I suppose you’re off to the pub?”

“Just called in to tell Sylv I’m off to do a little job in Trafalgar Street,” said Charlie, winking at his wife. “You’re doing a fine job on that knife, Ma. I could use that in my job, a fine sharp one like that. Just take care you don’t whetstone the ’ole thing away, though.”

“When I want advice from a sot like you, I’ll ask for it,” said Harriet. “Get off to your beer palace and your drunken mates.”

“Yes, I could use a good sharp knife like that,” said Charlie meditatively as he left the house.

“Don’t know what you’ve got against drink,” said Sylvia, greatly daring. “I like the odd Guinness myself these days. Or a port and lemon.” And she put down what she was doing and followed her husband.

Three days later, when she was putting out cyanide against the insects and hoping it would also tempt any stray dog in the neighbourhood that penetrated her backyard to have a lick, Harriet had a set-to with Jim Parsons in the next house. Jim had worked on the roads, and was now invalided out with a pittance of a pension.

“That stuff smells like a charnel house,” he shouted. “I wonder you don’t drop dead on the spot, just putting it out.”

“You wouldn’t understand the first thing about hygiene,” she shouted.

“No, I wouldn’t. But I tell you, if one of my pigeons dies, there’ll be another death follows on.”

Jim Parsons loved his birds more than he had ever loved mortal, and his love of them made Mrs. Blackstone wish she could wipe out the entire loft of them, and make a feathered carpet of Parsons’ backyard.

The end, when it came, was sudden. It was an early morning death, so most of the activity in Gladstone Road was centred on the back kitchens. Paul Dean, the builder, had left his long ladder outside the Blackstone residence at half-past six (he was not being blackmailed by Harriet, and merely did it for a quiet life). Since it was the second Thursday in the month, everyone in the street knew it was Mrs. Blackstone’s day for cleaning her windows. Being convinced that everyone had a duty to do the difficult things first — as they should eat their vegetables before their meat, if any — Harriet always began with the attic windows. She climbed the stepladder, as always, soon after seven o’clock. Her long skirts did not make things easy, but she was used to that problem, and she coped with that and with the bucket she was carrying. The police ascertained later that the glass in the right-hand side of the double window had been cleaned, and she had just begun on the left-hand side, abutting Jim Parsons’ house, when she fell. She dropped her bucket immediately, and managed to grasp the guttering along the top of Jim Parsons’ house. The iron was much eroded by the pigeon droppings, of which the gutter itself was nearly full, and a whole section broke off with her weight. She fell to her death on the pavement below, hitting her head on Parsons’ front step. She lay faceup, the face half-covered with pigeon dirt. The doctor at the other end of Trafalgar Street was called out from his breakfast, and he pronounced her dead.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 126, No. 3 & 4. Whole No. 769 & 770, September/October 2005» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.