As soon as Dr. Tsao had taken his leave with another deep bow,

Sergeant Hoong said, "Your honor, there are no marks of violence on that monk's body. For all I can see he died a natural death!" "We'll find that out this afternoon in the tribunal," the judge said. He asked the peasant, "Speak up, what did Mrs. Fan look like?"

"I don't know, excellency!" Pei Chiu wailed. "I didn't see her when she came to the farm, and when I found her body her face was all smeared with blood."

Judge Dee shrugged his shoulders. He said, "Ma Joong, you'll call the constables while Chiao Tai guards this rascal and the bodies. Have litters made of the branches here, and see to it that the bodies are conveyed to the tribunal. Put this man Pei Chiu in our jail. On your way back you go to the barn, and let Pei show you where he concealed that mat with the clothes of the victims. I'll now go back to the farm with Hoong to search the house and to question that girl."

The judge overtook Dr. Tsao as he was making his way carefully through the undergrowth, parting the branches with his long staff. His servant was waiting by the roadside, holding a donkey by the reins.

"I have to go to the farmhouse now, Dr. Tsao," Judge Dee said. "When I am through there, I shall avail myself of the opportunity to pay you a visit."

The doctor bowed deeply, the three strands of his beard fanning out like banners. He climbed on his donkey, laid his staff across the saddle and trotted off, the servant running behind him.

"I never in all my life saw such a magnificent beard," the judge said a little wistfully to Sergeant Hoong.

Back at the house judge Dee told Hoong to call the girl from the field. He himself went straight to the bedroom.

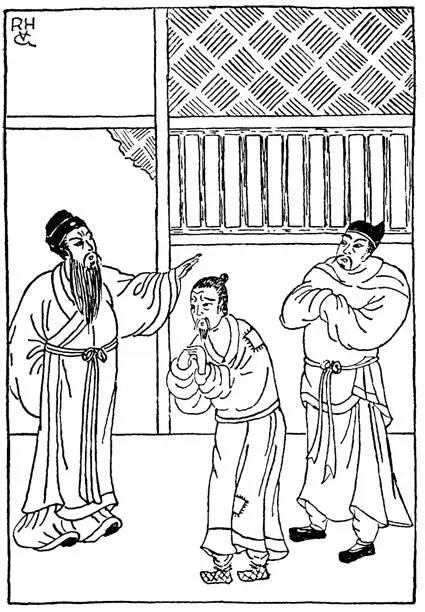

JUDGE DEE QUESTIONS AN OLD PEASANT

It contained one large bed, showing its bare wooden frame, two stools and a simple dressing table. In the corner near the door stood a small table with an oil lamp. As he looked down on the bare bed, his eye fell on a deep notch iii the wooden frame, near the head. The splinters looked fresh; the notch seemed to have been made quite recently. Shaking his head in doubt, the judge went over to the window. He saw that the wooden latch was broken. When about to turn away he noticed a folded piece of paper lying on the floor, directly below the window. He picked it up and found it contained a cheap woman's comb made of bone, decorated with three round pieces of colored glass. He wrapped it up again in the paper and put it in his sleeve. He asked himself perplexedly whether two women could be involved in this case. The handkerchief he had found in the hut belonged to a lady; this cheap comb was evidently the property of a peasant woman. With a sigh he went to the sitting room, where Hoong and Pei's daughter stood waiting for him.

Judge Dee noticed that the girl was mortally afraid of him; she hardly dared to look up. He said kindly, "Well, Soo-niang, your father told me that the other day you made a very nice fried chicken for the master!"

The girl gave him a shy look, then smiled a little. The judge went on.

"Country food is much better than the stuff we get in the city. I suppose that the lady liked it too?"

Soo-niang's face fell. She said with a shrug, "She was a proud one, was she. She sat on a stool in the bedroom and didn't even look round when I greeted her. Not she!"

"But she talked with you a bit when you were clearing the dishes away, didn't she?" Judge Dee asked.

"Then she was in bed already," the girl replied promptly. Judge Dee pensively stroked his beard. Then he asked, "By the way, do you know Mrs. Koo well? I mean the daughter of Dr. Tsao, who recently was married in the city?"

"I saw her once or twice from afar in the fields, with her brother," the girl replied. "People say she is a nice girl, not like all those city women."

"Well," Judge Dee said, "you'll now show us the way to Dr. Tsao's house. The constables down at the hut shall give you a horse. Thereafter you may accompany us back to the city; your father is going there too."

A PHILOSOPHER PROPOUNDS HIS LOFTY VIEWS; JUDGE DEE EXPLAINS A COMPLICATED MURDER

Judge Dee saw to his amzement that Dr. Tsao lived in a three-storied tower, built on a pine-clad hillock. He left Hoong and Soo-niang down in the small gatehouse, and followed Dr. Tsao upstairs.

While ascending the narrow staircase Dr. Tsao explained that in olden times the building had been a watchtower which had played an important role in local warfare. His family had owned it for generations, but they had always lived in the city. After the death of his father, who had been a tea merchant, Dr. Tsao had sold the house in the city and moved to the tower. "When we are up in my librarv, sir," he concluded, "you'll understand why."

Arrived in the octagonal room on the top floor, Dr. Tsao indicated the view from the broad window with a sweeping gesture and said, "I need space for thinking, sir! From my library here I contemplate heaven and earth, and therefrom derive my inspiration."

Judge Dee made an appropriate remark. He noticed that from the window on the north side one had a good view of the deserted temple, but that the stretch of road in front of it was concealed by the trees at the crossing.

When they were seated at the large desk piled with documents, Dr. Tsao asked eagerly, "What do they say in the capital about my system, your honor?"

The Judge didn't think he had ever heard Dr. Tsao's name mentioned, but he replied politely, "I heard that your philosophy is considered quite original."

The doctor looked pleased.

"Those who call me a pioneer in the field of independent thought are probably right!" he said with satisfaction. He poured the judge a cup of tea from the large teapot on the desk.

"Do you have any idea," Judge Dee asked, "what could have happened to your daughter?"

Dr. Tsao looked annoyed. He carefully arranged his beard over his breast, then answered with some asperity, "That girl, your honor, has been doing nothing, but causing me bother! And I shouldn't be bothered; it affects seriously the serenity of mind I need for my work. I taught her myself to read and write, and what happened? She is always reading the wrang books. History she reads, I ask you, sir, history! Nothing but the sad records of former people who hadn't yet learned to think clearly. A waste of time!"

"Well," Judge Dee said cautiously, "often one can learn a lot from other people's errors."

"Pah!" Dr. Tsao said.

"May I ask," the judge said politely, "why you married her to Mr. Koo Meng-pin? I heard that you consider Buddhism as senseless idolatry-and to a certain degree I share that view. But 1\1r. Koo is a fervent Buddhist."

"Ha!" Dr. Tsao exclaimed, "that was all arranged behind my back, by the women of the two families. All women, sir, are fools!" Judge Dee thought that a rather sweeping statement, but decided to let it pass. He asked, "Did your daughter know Fan Choong?"

The doctor threw up his arms.

"How could I possibly know that, your honor! Perhaps she has seen him once or twice, for instance last month when that insolent yokel came here to speak to me about a boundary stone. Imagine sir, me, a philosopher, and… a boundary stone!"

"I suppose both have their uses," Judge Dee remarked dryly. When Dr. Tsao shot him a suspicious look, he went on quickly, "I see that the wall over there is covered with shelves, but that they are practically empty. What happened to all your books? You must have had an extensive collection."

"I had indeed," Dr. Tsao replied indifferently, "but the more I read the less I find. I read, yes, but only to let myself be diverted by men's folly. Every time I was through with an author, I sent his works to my cousin Tsao Fen, in the capital. My cousin, I regret to say, sir, sadly lacks originality. He is incapable of independent thought!"

Читать дальше