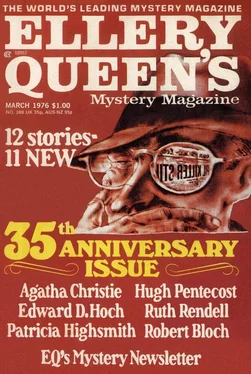

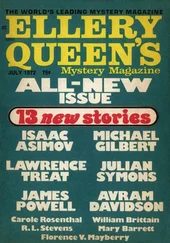

Аврам Дэвидсон - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Аврам Дэвидсон - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1976, Издательство: Davis Publications, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976

- Автор:

- Издательство:Davis Publications

- Жанр:

- Год:1976

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Perhaps not, sir. The law’s a funny thing. But there is evidence — as you call it, sir. None of them could have done it without my knowing.”

“But surely—”

“I know what I’m talking about, sir. There, listen to that.”

“That” was a creaking sound above their heads.

“The stairs, sir. Every time anyone goes up or down, the stairs creak something awful. It doesn’t matter how quiet you go. Mrs. Crabtree, she was lying on her bed, and Mr. Crabtree was fiddling about with them wretched stamps of his, and Miss Magdalen, she was up above working her sewing machine, and if any one of those three had come down the stairs I should have known it. And they didn’t!”

She spoke with a positive assurance which impressed the barrister. He thought: “A good witness. She’d carry weight.”

“You mightn’t have noticed.”

“Yes, I would. I’d have noticed without noticing, so to speak. Like you notice when a door shuts and somebody goes out.”

Sir Edward shifted his ground.

“That is three of them accounted for, but there is a fourth. Was Mr. Matthew Vaughan upstairs also?”

“No, but he was in the little room downstairs. Next door. And he was typewriting. You can hear it plain in here. His machine never stopped for a moment. Not for a moment, sir. I can swear to it. A nasty, irritating tap-tapping noise it is too.”

Sir Edward paused a few moments.

“It was you who found her, wasn’t it?”

“Yes, sir, it was. Lying there with blood on her poor hair. And no one hearing a sound on account of the tap-tapping of Mr. Matthew’s typewriter.”

“I understand you are positive that no one came to the house?”

“How could they, sir, without my knowing? The bell rings in here. And there’s only the one door.”

He looked at her straight in the face. “You were attached to Miss Crabtree?”

A warm glow — genuine, unmistakable — came into her face.

“Yes, indeed, I was, sir. But for Miss Crabtree — well, I’m getting on and I don’t mind speaking of it now. I got into trouble, sir, when I was a girl, and Miss Crabtree stood by me — took me back into her service, she did, when it was all over. I’d have died for her — I would indeed.”

Sir Edward knew sincerity when he heard it, and Martha was sincere.

“As far as you know, no one came to the door?”

“No one could have come.”

“I said as far as you know. But if Miss Crabtree had been expecting someone, if she opened the door to that someone herself?”

“Oh!”

“That’s possible, I suppose?” Sir Edward urged.

“It’s possible — yes — but it isn’t very likely. I mean—”

She was clearly taken aback. She couldn’t deny and yet she wanted to do so. Why? Because she knew that the truth lay elsewhere. Was that it? The four people in the house — one of them guilty?

Did Martha want to shield that guilty party? Had the stairs creaked? Had someone come stealthily down and did Martha know who that someone was?

She herself was honest — Sir Edward was convinced of that.

He pressed his point, watching her. “Miss Crabtree might have done that, I suppose? The window of that room faces the street. She might have seen whoever it was she was waiting for from the window and gone out into the hall and let him — or her — in. She might even have wished that no one should see the person.”

Martha looked troubled. She said at last, reluctantly, “Yes, you may be right, sir. I never thought of that. That she was expecting a gentleman — yes, it well might be.”

It was as though she began to perceive advantages in the idea.

“You were the last person to see her, were you not?”

“Yes, sir. After I’d cleared away the tea. I took the receipted books to her and the change from the money she’d given me.”

“Had she given the money to you in five-pound notes?”

“A five-pound note, sir,” said Martha in a shocked voice. “The books never came up as high as five pounds. I’m very careful.”

“Where did she keep her money?”

“I don’t rightly know, sir. I should say that she carried it about with her — in her black velvet bag. But of course she may have kept it in one of the drawers in her bedroom that were locked. She was very fond of locking up things, though prone to lose her keys.”

Sir Edward nodded. “You don’t know how much money she had — in five-pound notes, I mean?”

“No, sir, I couldn’t say what the exact amount was.”

“And she said nothing to you that could lead you to believe she was expecting anybody?”

“No, sir.”

“You’re quite sure? What exactly did she say?”

“Well,” Martha considered, “she said the butcher was nothing more than a rogue and a cheat, and she said I’d had in a quarter of a pound of tea more than I ought, and she said Mrs. Crabtree was full of nonsense for not liking to eat margarine, and she didn’t like one of the sixpences I’d brought back — one of the new ones with oak leaves on it — she said it was bad, and I had a lot of trouble to convince her. And she said — oh, that the fishmonger had sent haddocks instead of whitings, and had I told him about it, and I said I had — and, really, I think that’s all, sir.”

Martha’s speech had made the deceased lady loom clear to Sir Edward as a detailed description would never have done. He said casually, “Rather a difficult mistress to please, eh?”

“A bit fussy, but there, poor dear, she didn’t often get out, and staying cooped up she had to have something to amuse herself like. She was pernickety but kind-hearted — never a beggar sent away from the door without something. Fussy she may have been, but a real charitable lady.”

“I am glad, Martha, that she leaves one person to regret her.”

The old servant caught her breath.

“You mean — oh, but they were all fond of her — really — underneath. They all had words with her now and again, but it didn’t mean anything.”

Sir Edward lifted his head. There was a creak above.

“That’s Miss Magdalen coming down.”

“How do you know?” he shot at her.

The old woman flushed. “I know her step,” she explained.

Sir Edward left the kitchen rapidly. Martha had been right. Magdalen had just reached the bottom stair. She looked at him hopefully.

“Not very far as yet,” said Sir Edward, answering her look, and added, “You don’t happen to know what letters your aunt received on the day of her death?”

“They are all together. The police have been through them, of course.”

She led the way to the big living room, and unlocking a drawer, took out a large black velvet bag with an old-fashioned silver clasp.

“This is aunt’s bag. Everything is in here just as it was on the day of her death. I’ve kept it like that.”

Sir Edward thanked her and proceeded to turn out the contents of the bag on the table. It was, he fancied, a fair specimen of an eccentric elderly lady’s handbag.

There was some old silver change, two ginger nuts, three newspaper clippings, a trashy, printed poem about the unemployed, an Old Moore’s Almanack, a large piece of camphor, some spectacles, and three letters. A spidery one from someone called “Cousin Lucy,” a bill for repairing a watch, and an appeal from a charitable institution.

Sir Edward went through everything very carefully, then repacked the bag and handed it to Magdalen with a sigh.

“Thank you, Miss Magdalen. I’m afraid there isn’t much there.”

He rose, observed that the window commanded a good view of the front-door steps, then took Magdalen’s hand in his.

“You are going?”

“Yes.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 67, No. 3. Whole No. 388, March 1976» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.