“You mean in the firing line,” said the Saint.

Pelton shrugged.

“If you’re in charge of the raiding party, so much the better — so long as you remember to dodge the bullets when the crucial moment comes. But we’ll be relying on your help beforehand — we’ll need to know what sort of attack he intends to mount, so that we can prepare to meet it at minimum risk to our own forces.”

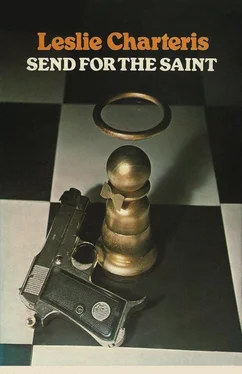

“The probabilities look right,” Simon said as he stood up. “But it’s still guesswork at this stage. I’ll pass on whatever I find out tomorrow.” He paused, looking speculatively at Pelton. “By the way, just so that I can settle a bet with myself — are you a chess player, by any chance?”

Pelton looked mildly surprised and said: “As a matter of fact, yes. I enjoy a game occasionally. Why do you ask?”

“Just tell me what your favourite opening is,” Simon said: “the one you like to use yourself, when you’re playing as White, let’s say.”

“King’s Gambit,” Pelton said. “Or one of the other pawn gambits.”

“Thanks,” said the Saint with the ghost of a smile. “I just won a bet with myself.”

On the short drive back, Ruth asked him about that parting remark.

“I don’t know the game,” she said. “What did you mean — about openings, and gambits?”

“It would take too long to explain now,” he told her. “Let’s just say I discovered something your boss has in common with Rockham.”

His occasional excursions to the wall and over had become almost routine by now, and in a few minutes he was back in his room, his denims, shirt, and pullover were neatly folded over the chair, and the black plimsolls neatly aligned under it, with absolutely no sign of any hurry in the manner of their arrangement. And in a few minutes more he really was peacefully asleep again, as if he had done nothing else since going to bed the night before.

In those few minutes, however, he had administered himself a sober warning: not to push his luck with these nocturnal excursions too far. Until then, Lembick and Cawber had had no reason to be suspicious of him and hence to subject him to special surveillance. Now, even without suspicion, they had motives to look for or even to manufacture some evidence that would discredit him. And it could hardly be long before even their slower wits visualized his room as a tempting site for some nefarious operation.

He was roused in the morning by a weird sound that droned mystifyingly over the blurred threshold of his consciousness. At first it seemed like the despairing death-cry of a stricken poltergeist... or was it a wailing banshee come to mourn in anticipation of an imminent human demise... or was there some still more unearthly explanation that would occur to him once he was properly awake? It was a plaintive penetrating sound that rose and fell in ear-torturing cadences, a plangent ululation such as never came from the mouth of man nor beast.

The Saint rolled out of bed and looked out of the window.

It was Lembick, playing the bagpipes.

Nor was this torture inflicted on his fellows for his own private pleasure; a fact that became clear when Rockham briefed him that morning for the next day’s mission.

Rockham gave away no more than he had to. What he did give away included the name Instrood, and the location: Braizedown Hall.

“It’s a straightforward enough plan,” he said. “I’m briefing you separately as you’ll be playing the part of Officer in Command. But don’t run away with the idea that you’re in command of the mission,” he added. “Because I’ll be there myself, right beside you. As your Corporal.”

“That’s nice and trusting of you,” said the Saint.

Rockham turned those pale eyes on him.

“A good mercenary commander never separates himself for long from his troops,” he replied. “Now — Braizedown Hall is under constant guard. A platoon of men, day and night. We could always try storming the place with superior numbers, but there’s a neater way. We take the place of the guard.”

Simon raised an eyebrow.

“How?”

“The Paras are due to hand over tomorrow to another regiment. The Lowland Light Infantry. And we’ve enough of their uniforms to make up a plausible- looking platoon. Lembick has an encyclopaedic knowledge of the Scots regiments. I’ve put him in charge of the drill.”

The Saint thought about it. It was a bold and yet simple idea, the sort he would have expected from Rockham. He looked appraisingly at this man with the big square head, the determined jaw, the powerful hands; and he wondered what sort of conventional military strategist he would have made, if he had not chosen the path of lawless violence.

“What about the real platoon?” he asked.

“We divert them — send them on a circular tour around the country,” said Rockham, smiling. “And then we roll up in their place. And within twenty minutes after that, we roll out again — with the valuable Mr Instrood.”

All that day, the selected group of twenty-five men were drilled by Lembick in their tartan trews and battle-blouses. Tam o’shanters, those peculiarly Scottish woollen berets worn aslant, completed the uniform of that unique regiment — a regiment so elite and exclusive that even a person knowledgeable in military affairs of the time might be forgiven for never having heard of the Lowland Light Infantry.

Simon himself received special detailed briefing from Lembick on his role as Captain — and more than once he drew thankfully on his hasty studies to supply the general knowledge that was assumed of him.

When he woke himself that night for his rendezvous with Ruth Barnaby, it was with a simultaneous reprise of the cautionary thought with which he had fallen asleep after his last sortie. He made his way to the toilet as usual, but before switching on the light took a long look out of the window. And in the darkness below, he detected at one point the intermittent red glow of a cigarette, like an over- stimulated glowworm.

Therefore, after making normal use of the plumbing, instead of returning to his room or using the drainpipe exit route that he had established, he went boldly down the stairs and ambled out of the bedroom block.

He stood briefly outside the door, breathing in the cool night air and now and again gazing up at the few faint stars that were visible. When his eyes had adjusted fully to the dark, he began a leisurely stroll around. As soon as he moved off he saw out of the corner of his eye the black shadow that detached itself from a wall of the next block; and throughout the unhurried circuit he made of the main buildings he knew that the shadow was following at a discreet distance behind him.

The Saint smiled indulgently and allowed the pantomime to continue until he chose the moment to make an abrupt about-turn and say: “Why not join me, chum, instead of trailing along like a lost beagle?”

It was Lembick who loomed recognisably out of the dark. And said: “Where d’ye think you’re going?”

“For a walk,” said the Saint imperturbably. “I got the fidgets — tossing and turning, couldn’t sleep.”

“Nerves, maybe?” Lembick sneered. “About the job tomorrow?”

“No nerves,” rasped the Saint, in the abrasive tones of Gascott. “It’s a sort of muscle restlessness. Stops you settling down to sleep. The only cure is to move around and work it off.”

“You must need more exercise,” Lemback said. “That can be arranged.”

The Saint stood and faced him.

“Lembick,” he said, with a kind of military authority that he knew would have effect, “let’s stop this nonsense. We’re in this together now. We’ve got to work together. Let’s call it quits and get on with it.” He stuck out his hand disarmingly. “OK?”

Читать дальше