Cawber spoke.

“OK, let’s see if you’re as cool out there as you’re smart in here.”

The voice proclaimed Cawber’s New York origins, and the sentence was among the longest Gascott had heard him utter.

Gascott seemed totally at his ease, his relaxation as tangible as Lembick and Cawber’s tension. He took a long silencer out of his pocket and fitted it to the revolver with calm efficiency, almost caressing it into position until it settled home. The job took him just a few moments, yet the actions themselves seemed completely unhurried.

He let the gun swing around carelessly, till it pointed almost straight at the American’s ear.

“Nice long string of words, Cawber — for you!” he sneered. Gascott’s harsh yet cultured voice suggested both his ruthlessness and an army-officer background. “You’re getting almost fluent.”

Cawber caught the gun by its silencer and twisted it savagely aside. “Just remember, Gascott,” he growled. “We’ll be watching. And tonight” — he tapped the cine camera with a stubby forefinger — “so will Rockham. So you just better be sure and get it right.”

Gascott chuckled mirthlessly as he leaned over and flicked a lever on the cine camera.

“You’d better get your own end of it right. We wouldn’t want the film running backwards, would we? And don’t forget the telephoto lens — there’s a good little hoodlum.”

Gascott tucked the gun into a deep inside pocket of his dark raincoat; and even before Lembick had brought the car completely to a halt, he had opened the door and was gone.

Gascott was a man who had passed through many schools of violence, a man to whom sudden death was a far from unfamiliar experience, who had faced as well as delivered it down the barrels of many assorted guns. But only a few weeks before, he had known nothing of Lembick, or Cawber, or Rockham, and he might well have found it hard to believe that on this grey November afternoon he would be carrying out The Squad’s death sentence on Albert Nobbins.

Lembick and Cawber watched with viciously grudging approval as his tall figure crossed the grass with easy strides, in a course that made a shallow angle with the path along which Nobbins’ much shorter steps were taking him. It was Lembick and Cawber’s fierce hope that Gascott would fudge the job; but they had seen enough of him in training to be virtually certain they would be disappointed; and they festered with an impotent smouldering rancour at the thought of his growing prestige with Rockham.

“Smartass!”

Cawber spat out the words as he screwed a telephoto lens to the camera turret and wound down the car window. He rested the heavy camera on the window-ledge and squinted through the viewfinder, keeping Gascott’s long-striding form in the small centre square which represented the magnified field of view.

Gascott reached the path about twenty yards behind Nobbins, and rapidly began to close the gap. Lembick stopped the car and raised the binoculars to his eyes; Cawber started the camera.

Neither man heard the well-muffled shots, but Lembick saw the elongated revolver twitch three times in Gascott’s steady hand. With the first shot, Nobbins seemed to stop, as if there was something he had suddenly remembered; and then, as the other two shots went home, he crumpled, pitched forward on his face, and lay still.

Lembick continued to watch for a few moments as a dark stain slowly spread through Nobbin’s coat, just above the centre of his back. Then, with a further glance around to establish that none of the distant figures in the park who were nobly getting wet in the cause of canine indulgence had noticed anything untoward, he drove the car forward till it was level with Gascott.

And Gascott came back across the grass with the same long measured strides, no whit more hurried than before.

As soon as the tall gunman had eased himself back into the car, Lembick drove smartly away. Gascott unscrewed the silencer and put it back in his pocket.

“Any criticisms — gentlemen?” he said, giving the final word a satirical intonation that made it an insult.

“Nothing much wrong with that,” Lembick said shortly. The words seemed wrung from his lips. “A professional job, I’d say,” After a pause he added: “Are you quite sure he’s dead, though?”

“With three bullets through the heart, would you be planning your next year’s holiday — laddie?”

Lembick nodded, keeping himself under control with visible difficulty.

“All right, we know you’re a good shot,” he said harshly. “We’ve seen you on the range.”

Gascott turned to Cawber.

“What about Alfred Hitchcock’s opinion?” he rasped.

Cawber glowered.

“I guess you did a pretty good job. But you — you shoulda gotten closer.”

“But that would have been too easy. You know — unsporting!”

Gascott laughed his curiously loud metallic laugh, and Cawber and Lembick eyed him malevolently. He knew exactly the line of English gentlemanly phraseology calculated to incense them both.

“No, no,” he went on, “that certainly wouldn’t have been playing the game. No real target practice at all! But don’t you worry about Mike Argyle — he’s not going to be in our hair any more.”

There was a terrible calm finality in Gascott’s last sentence that chilled even the hardened trainers of The Squad.

“Well, anyway, Rockham should be pleased enough,” Lembick grunted, still controlling his antagonism with an effort.

Again Gascott’s chilling laugh rang out.

“Poor old Mike — a posthumous film-star! But if you’re good boys,” he rasped confidingly, “I’ll ask Rockham to let you. bring around the ice creams in the interval.”

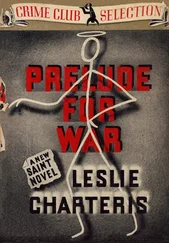

It was Albert Nobbins they had left lying there face down in the mud, with the rain pattering on to his back. But the men of The Squad knew him only as Mike Argyle, a name he had chosen for himself as more befitting the sort of personage he would have liked to be, under which he had lived among them for the six fear-ridden weeks of his masquerade. Likewise, the man who had fired the gun was know to the Squad as George Gascott, and by no other name. But to some, despite the changes in his appearance, voice, and manner, he would have been recognisable as Simon Templar — more widely known as “The Saint”.

The three weeks Simon Templar had spent in Brixton Prison were among the longest in his memory.

For more years than he cared to count, the police of at least half a dozen countries around the world had been longing to put the Saint behind bars; while for his part the Saint — whose preference was decidedly for the kind of bars that dispense liquid conviviality — had just as consistently declined to gratify their police-manly yearnings. His chief occupation through those years had been the noble sport of thumping the Ungodly on the hooter, but he had had almost as much fun out of tweaking the proboscis of the often absurd Guardians of the Law; and best of all he enjoyed the sublimely compounded entertainment he derived from mounting his irreverent assaults on both sets of noses simultaneously.

Inevitably in that career of debonair and preposterous lawlessness, he had had his hair’s-breadth escapes. But despite the best endeavours of some dedicated policemen, he had never yet heard a British prison gate clang shut behind him.

Until the events that were begun by Pelton’s phone call.

“Simon Templar?” said the clipped precise voice. “Pelton. David Pelton. Colonel. I expect you’ll remember me.” And as Simon groped through his memory the voice went on with the same brisk precision. “We met, as I recall, three times. The last occasion was just under six years ago. You were serving with some cloak-and-dagger outfit under a bloke named Hamilton, and I was one of your London contacts. You’ll remember that I was then — as indeed I still am now — in one of the...” — here the voice paused fractionally — “Government Departments.”

Читать дальше