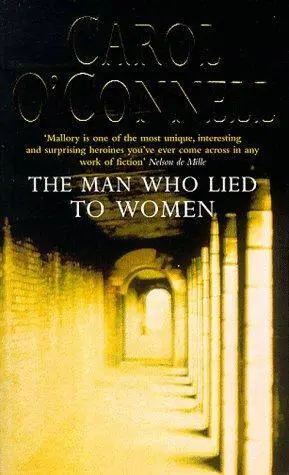

Carol O’Connell

The Man Who Lied To Women

The Man Who Cast Two Shadows

The second book in the Kathleen Mallory series, 1995

Rain rat-tatted on the plastic hood of her slicker. She could feel the drops, but not hear them. She had come out this morning without hearing aid or bifocals. Her landscape was dream quiet and blurred free of the small, marring details of candy wrappers and cigarette butts.

The smell of wet dog fur hurried past her. She was slow to focus on the animal’s rump before it had gone off the path and up the steep incline of grass clotted with bushes. Now, the dog was jerked sharply at the neck by an unseen hand, and airborne in a backward somersault.

Squinting for clarity, Cora realized the dog’s leash was caught up in the brambles. The animal freed itself with a panic of yanks and pulls, then scrambled up the slanted earth, disappearing over the rise.

Cora tucked in a wind-whipped strand of white hair and became invisible again, her hunter’s green slicker blending in with all the plant life not yet turned to the gray spectrum of deep December.

She looked down at her watch. She should leave the park now, she knew that, but an inviting procession of empty benches stretched out along the path ahead, drops of water waxing on their green paint. She sat down on the first bench, minding the old bones which reprimanded her for taking them out in the rain.

But, she argued with the bones, it was only the rain that made her feel safe in the park. She reasoned that muggers would not work in foul weather, nor did she believe them to be early risers.

Her body’s closing remark was a stab of arthritis as she bent her arm over the back of the bench and rested one hand on the wood. A moment later, she felt a trickling sensation on her wrist. A dark spot was crawling about on her white crepe flesh. She bowed her head until the crawling spot on the back of her hand was within a few inches of her near-sighted blue eyes.

She sucked in her breath over long, yellowed teeth.

It was a carrion beetle, a long-lived insect whose vocation was the desecration and desiccation of corpses. But surely this tiny undertaker had come too soon. There were rules of nature to be observed while an old woman still drew breath. Perhaps the insect had become confused by the unseasonably warm weather. No matter, the beetle would have to return for her another day.

And now, a second creature entered her narrow field of unblurred vision, its eight legs in crawling pursuit of the beetle.

Oh, this could not be happening.

This particular arachnid was bound by law to die in autumn and be eaten by its children. The spider had overstayed its life; it did not belong in December. And now the unnatural lawbreaker was within an inch of its prey, the beetle.

Ah, but this was too much violence so early in the day.

The elderly naturalist flicked her wrist and sent the beetle flying far and wide of the spider’s jaws. At her sudden movement, the spider stopped, then turned and crawled away, all eight hands empty.

The serenity of the morning restored, Cora stared out across the widest part of the lake, gray mirror of the sky. Slowly, her gaze drifted inland to the narrow leg of water close to the path. More like a pond it was, still and stagnant, darker here. And beyond this pond, and darker still, were two large shapes near the water’s edge, two black umbrellas talking – if she knew the stance of conversation. And she did.

The taller umbrella had long legs of tan, and the shorter umbrella had blue legs. Now the blue-legged umbrella was backing away. The tall umbrella shot out one white hand to fetch Blue Legs back to him again.

Cora smiled. Young lovers they must be. And now she deduced that it was a covert meeting. The tall umbrella shifted and turned, showing a flash of white face as he spun round to see if he was seen. He held fast to Blue Legs, who pulled back, wanting to leave him now. Gold hair shone bright against black as her umbrella tipped back and flew from her hand, upending itself in the pond, its handle sticking up as a sail-bare mast. It turned slowly, then twirled faster and faster in a sudden rush of clean, rain-washed air.

The tall umbrella stooped low. Was he retrieving something from the ground? Yes, and he brought it up to Blue Legs’ face, and then obscured Cora’s view with his umbrella as he danced Blue Legs in a half turn.

It must be a gift he was giving her, thought Cora, squinting. Blue Legs must be pleased with it for she had ceased to resist the tall umbrella. Stunned she seemed, leaning against him now, not struggling at all. Something bright and red adorned the gold hair, flowering to one side of Blue Legs’ face as they completed the half turn, not dancing any longer, but standing still and close.

A prelude to a kiss?

Cora looked down at her watch. Well, they would have their privacy, for she was already minutes late. She rose up on aching legs.

Cora was turning away from the lovers as an umbrella was falling to the ground, and two large hands grasped the head of Blue Legs. Cora was seconds down the path when the fingers were entering the bright curls, when the golden head was twisted sharply, unnaturally, setting Blue Legs free of the constraints of minutes and seconds as the living understood time.

20 December

Her fixation with machines had its roots in the telephone company nets which spread around the planet.

The child had only the numbers written on her palm in ink, written there so she could not be lost. All but the last four numbers had disappeared in a wet smudge of blood.

Over time, she had learned to beg small change from prostitutes, the only adults who would not turn her over to the social workers. She would put the coins into the public telephones and dial three untried numbers and then the four she knew. If a woman answered, she would say, ‘It’s Kathy. I’m lost.’

When she was seven years old, she could duplicate the tones of the public telephones by whistling with perfect pitch to open the circuits for long-distance calls, and she had learned all the international codes. She could also whistle the telephone out of its change. And so the telephone network fed her small body and her fixation. The constants of a thousand calls were the simple message and the last four digits of a telephone number.

All these years later, there were still women, around the globe and all its time zones, all haunted by the disembodied voice of a child who was lost out there in the cyberspace of the telephone company.

Detective Sergeant Riker of Special Crimes Section knew nothing of Kathy Mallory’s origins. No one did. She had arrived in the life of Inspector Louis Markowitz as a fullblown person, aged ten, or maybe eleven. Who could be certain about the age of a street kid? And her history belonged to her alone.

The inspector’s wife, Helen Markowitz, had washed the child and discovered something remarkable beneath the patina of dirt. A waterfall of clean, burnished-gold hair was parted to expose the glittering green eyes, the painfully beautiful face of delicately sculpted angles and hollows, and the full, red mouth. Kathy’s intelligence had seemed like an excess of gifts.

Fourteen years later, according to the homicide report of Detective Palanski, she was lying dead on an autopsy table just the other side of the door.

Sergeant Riker pushed through the door and into the shock of cold air. A pool of bright light surrounded the metal table, the carts, and instruments which included the incongruous carpentry tools of drill and saw. He looked down at the partially sheeted body.

Читать дальше